Gabriele Goria a Report on the Meditation-Room Experiment at CARPA 5

Gabriele Goria a Report on the Meditation-Room Experiment at CARPA 5

- Gabriele Goria

As my contribution to CARPA 5, I arranged a meditation room for the participants at the colloquium. This experiment was an introduction to my artistic research on meditative silence. My concern was not to expose meditation as the object of an inquiry, but to share it as a partner of dialogue in the framework of the conference.

The specific commitment of my work is to approach formal sitting meditation as an artistic practice. In this experiment, I was interested in how the participants experienced meditative silence, the spatial relationships with the other meditators, and with the room.

Genesis of the Experiment

Sharing silence was launched in March 2017. In the period of March–May 2017, I meditated one hour a day in different spaces of the Theatre Academy in Helsinki. Students and staff of the school were invited to join me in silence. Before leaving the space, the participants had the chance to leave a comment by writing or drawing. This format was devised for facilitating mindfulness experiences, as well as for bringing awareness on the aesthetic and choreographic features of meditative group-sittings.

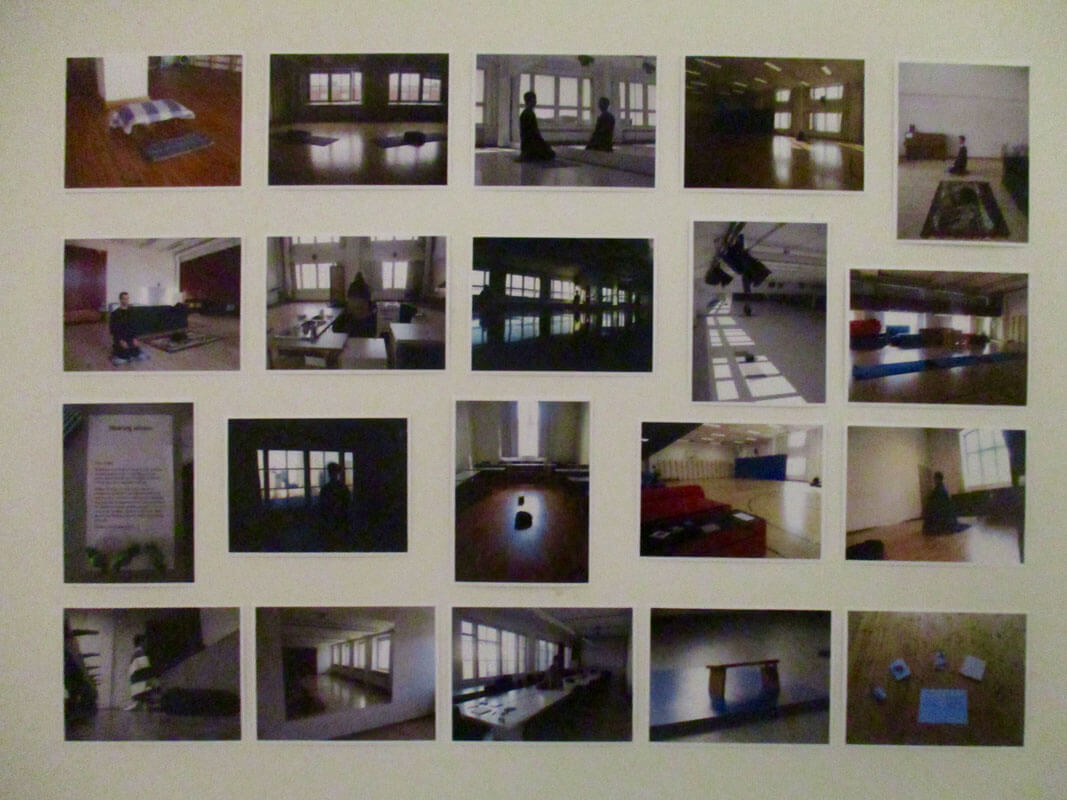

Some of the participants came back many times. A few of them took photos of the space and of myself meditating. These pictures made me realize that the choice of my meditation posture, as well as my place in the room, created a network of spatial relationships and dialogues.

The diverse spaces of the Theatre Academy offered many settings to play with. I sat in small rooms, dance studios, auditoriums, lecture rooms and in the big gym too. Many other places of the building remain to be explored. So far, I did not test locations such as the entrance hall, the corridors and the stairs. My concern for making the participants feel comfortable in joining the meditation played a major role in my choice of the spaces. I wanted to find a compromise between the visual potential of the setting and its suitability for a serious practice of meditation.

- Gabriele Goria

A few participants commented that silence gave them space for processing life issues. They wrote in the guest book:

I found the stopping and sitting as a powerful way to clear things in my mind and see the essential. (Sharing Silence – Guest Book 2017, 3)

I took the liberty of stealing a moment for myself for the love of existing. (Ibid., 15)

One visitor reported that my choice of sitting facing the window gave her the feeling she was the performer, or the focus of the event. In fact, at the beginning of the meditation she sat on the opposite side of the room, but throughout the hour, she felt compelled to move closer.

In general, the visitors supported my concentration. At times though, I was too excited of the presence of an ‘audience’ and it took me effort to centre myself again. When nobody came and visited me, there were moments when I had to fight the temptation of feeling lonely and failing. This reminded me of my greatest challenge in dialogical situations: staying open, and reaching out without losing the centre. I began to understand Sharing silence as an experience of dialogue. A simple action such as sitting, engaged myself in a complex negotiation between myself, my meditative practice, the space, and the presence – or absence – of other people.

- Gabriele Goria

Sharing Silence at CARPA 5

For CARPA 5, I further developed this experiment by recreating a meditation room in an auditorium of the Theatre Academy. On the wall close by the entrance door, I installed a photographic exhibition with the images of the various settings explored in my previous experiments. I arranged matrasses, meditation cushions, blankets, and benches in diverse orientations and levels, in order to provide the participants with a variety of choices. In particular, I wanted to break the squared shape of the room by disposing the central props into diagonal lines.

These were the words people read at the entrance door of the meditation room:

Dear visitor,

this meditation room is for you. You are welcome to stop by for as long as you want. Feel free to practice your meditation technique, or to rest and witness.

According to your needs, you can try different postures and places. Pay attention to your spatial relationship with the room, its objects, and the other meditators.

Before leaving the room, you can express your observations and feelings on the guest book. Please, respect silence throughout your visit. (Sharing Silence – Guest Book 2017, 2)

- Gabriele Goria

Especially during the breaks between the colloquium’s sessions, there was a regular flow of visitors in the meditation room. Many comments were written on the pages of the guest book. The most recurrent feedback was the request to continue this experiment, or to create a permanent meditation space. A participant wrote:

I wish there was a room like this in all conferences, schools and workplaces. (Sharing Silence – Guest Book 2017, 20)

Another noted:

I’ve found this space to be a wonderful place to take a break from the usual social stress present in conferences. (Ibid.,28)

And another commented:

I’m convinced that a meditation room should be part of every institution. (Ibid., 27)

Some visitors compared the arrangement of the room to a scenography, or a stage. Furthermore, the postures, the clothes, and the mutual positions of other meditators were perceived as elements of theatre, triggering poetic images, or even sociological reflections about power relationships.

For example, my choice of sitting on upper or lower levels in the room, or my orientation towards the wall, the window, or the centre, was understood as a statement, which generated various metaphors. One visitor wrote:

Where do you choose to sit? And what about the master and king I am reminded of? Yesterday master, today king. Or humble human being. Shape shifting. But very influential for the ‘scene’ as a whole, and there is this element of theatre, stage. What will it look like when I enter the room today? What will it feel like? (Ibid., 25–26)

When I sat on the table facing the wall, one participant experienced a feeling of rejection. Some exited the room immediately after entering. On the other hand, when I meditated on the floor in the corner of the room, and I faced the audience, the same visitor told me she felt welcome to inhabit the space. This is her comment:

I felt a beautiful welcoming as I entered your silent space today. You were sitting facing to the open space and I felt immediately connected and embraced by peace and compassion.

The feeling was totally opposite as I entered on Thursday. You were sitting high up on a table facing the wall turned away from the openness of the space and so was the other person also facing the wall, sitting tightly and close to it.

This created in me a sense of rejection and resentment and also being left alone and outside. I know this is the way of many meditation techniques encourage it and I’ve done it myself in zazen sessions. But as I aimed to come with open mind and not anticipating any formal cognition of silent meditation this entrance felt awkward.

But anyway as I reached the neutral silent space in me, I felt fine and encouraged by the co-meditators to share the silent space in meditation. (Ibid., 30)

- Gabriele Goria

- Gabriele Goria

Sharing silence was also interpreted as an invitation to explore, understand, and transform one’s relationship with meditation and silence. One visitor wrote a long reflection about her journey from traditional meditative techniques to a spontaneous ‘silent witnessing’ (Sharing Silence – Guest Book 2017, 31):

By fully claiming my alignment with my centred being […], I free myself from being ruled or formed by external opinions or behaviours or techniques and instead, my experience of silence and meditation becomes self-validated, self-reflective and self-actualizing. This is the silent space within me that spontaneously resonates with the deep neutral space of being within other people and within the living world of nature around me. (Ibid., 31–32)

Finally, the experiment enlightened some aesthetic and artistic features of meditative silence. In the words of one participant, the meditation room became a “space where silence performs a perfect piece. (Ibid., 7)11

Conclusion

The current landscape of artistic research on meditation presents a variety of different methodologies. The performance artist and theorist Phillip Zarrilli (2002), for example, investigates meditation as a training for accessing and transforming the creative process. A similar approach is carried on by Naomi Lefebvre Sell (Whatley & Lefebvre Sell 2014) in the field of dance and somatics.

A different line of research intertwines meditation with other artistic practices in order to entangle them into a meditative or spiritual framework. For instance, the visual artist Su-Lien Hsieh (2010) focuses on the interaction between her painting practice and several Buddhist meditative techniques, such as bowings, mandalas, and breath-awareness.

In other cases, the artistic practice itself can be understood, to diverse extents, as a form of meditation. The vocal artist, performer and choreographer Meredith Monk (2010) – just to mention one – openly bridges her artistic practice to her spiritual practice, drawing parallels between the Buddhist notion of dharma and making art.

By contrast, Sharing silence follows an alternative track: in this research, formal sitting meditation is investigated as an artistic practice in its own right. Without the need of involving other practices, my research approaches meditation as an authentic artistic experience, more than as a training for transforming the artistic performance. This work raises questions about the place and the function of meditation in performing arts, in artistic research, in academic institutions, as well as in our society.

References

Hsieh, Su-Lien. 2010. Buddhist Meditation as Art Practice: Art Practice as Buddhist Meditation. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University.

Monk, Meredith. 2010. “The Art of Being Present.” Lion’s Roar: Buddhist Wisdom for our Time September 11. Online journal. Accessed 14 November 2017. www.lionsroar.com/the-art-o-being-present

Whatley, Sarah & Lefebvre Sell, Naomi. 2014. “Dancing and Flourishing: Mindful Meditation in Dance-Making and Performing.” In Dance, Somatics and Spiritualities: Contemporary Sacred Narratives, editors Amanda Williamson, Glenna Batson, Sarah Whatley & Rebecca, Weber, 437–458. Chicago: Intellect.

Zarrilli, Phillip. 2002. Acting (Re)Considered: A theoretical and Practical Guide. London: Routledge.

Biography

Gabriele Goria is an Italian actor, Kung Fu teacher and theatre pedagogue. As a Doctoral Candidate at the Performing Arts Research Centre (Tutke) at the Theatre Academy University of the Arts Helsinki, he is currently investigating Vipassanā meditation as an artistic practice.