Abstract

Our notions of dramaturgy and human agency are today challenged by technical systems we are surrounded by. At the same time, dramaturgy might offer a critical perspective for inspecting the use and discourses on technology. Building on experiences from the ongoing research process and the recent artistic production of kinetic audiobook performance Manuaali (A Manual, 2022), I will ponder questions emerging from the practice of working with sound technology as dramaturg and artist-researcher. In dialogue with the concept of technical ensemble, developed by French philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon, I observe how machines and humans turn into shared agential compounds in the context of performance, and outline briefly what kind of knowledge does this composite notion of dramaturgy and technology push forward. This text is a rewritten and slightly expanded version of the original presentation in CARPA8 at Theatre Academy.

The machine remains one of the obscure zones of our civilization, at all social levels.

(Simondon 2017, 257)

These words of philosopher Gilbert Simondon still resonate with us after sixty-five years that have passed since they were written down in 1958. The rise of automatic computational processes has further complexified the division to the world of technics and human life-world. When it’s working, algorithmic computation blurs the distinction between artificial and human. On the other hand, the gap between what is observable for us as users, and what is hidden underneath the interfacial design, has been deepened and our means for understanding the mechanics applied severely obscured.

“Obscure” is by definition something which is not well known, or something difficult to understand. Here obscurity offers a point of departure for discussing the relationship between dramaturgy and technology, since dramaturgy deals with things which are in the middle of the process and not available for consciousness in a pure or stable state. At best, the difficulty to understand might lead us to experiment with new ways of understanding, which do not simplify the issue at hand. Concerning the theme of this colloquium – dramaturgy and artistic research – I’d like to dig a bit into questions: how is our understanding of dramaturgy today challenged by technological systems we are surrounded by and how can the perspective of dramaturgy offer a critical point of view to the discourses and uses of technology?

Dramaturgy of technical failure

From 2017 onwards I have been working in collaboration with composer and sound artist Walter Sallinen. What I have found specifically interesting in working with sound is how sound modification tools, which are primarily designed for making music, affect and alter our perception of language, that is encountered not as marks on screen or page nor verbal expression in conventional sense, but as vibrating material present in space.

This is one of the main questions explored in Manuaali, which is at the same time a work of audio literature, conceptual musical composition and live performance. In this kinetic work of literary sound art, movement becomes a central dramaturgical motive which organizes voice, human body and technical appliances into a strangely functional whole.

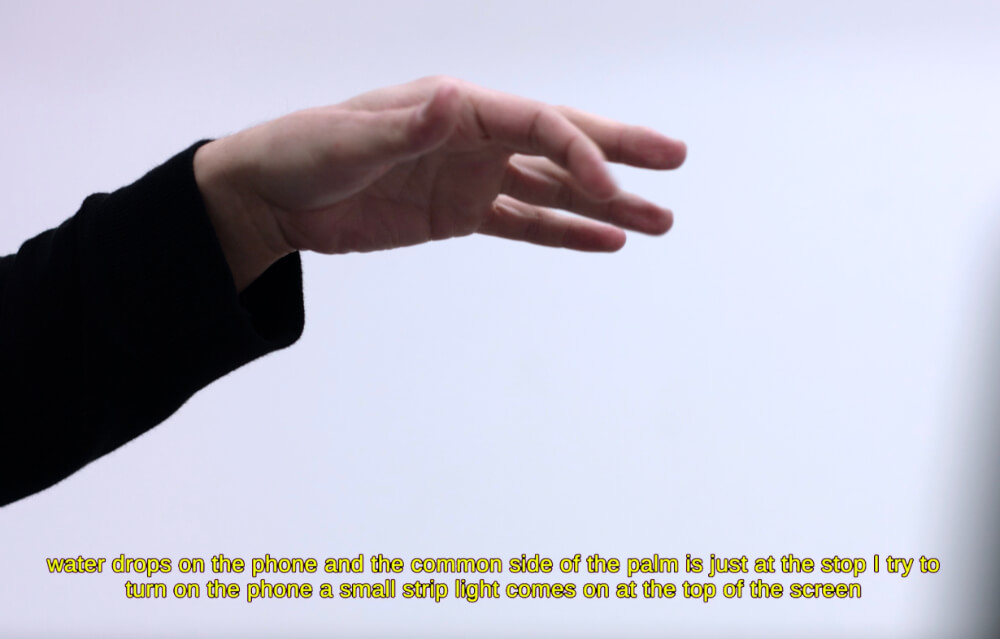

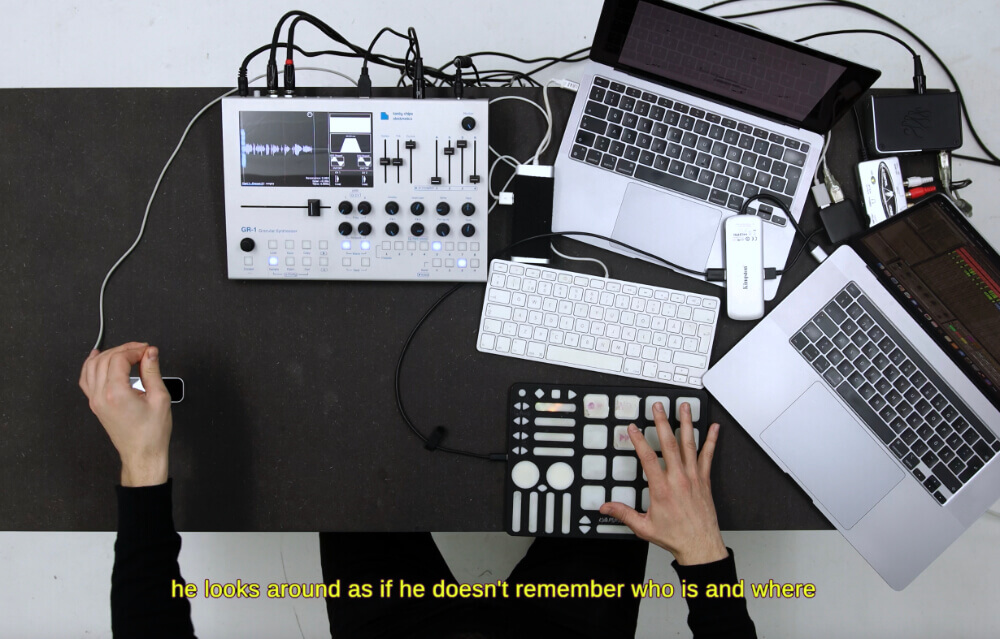

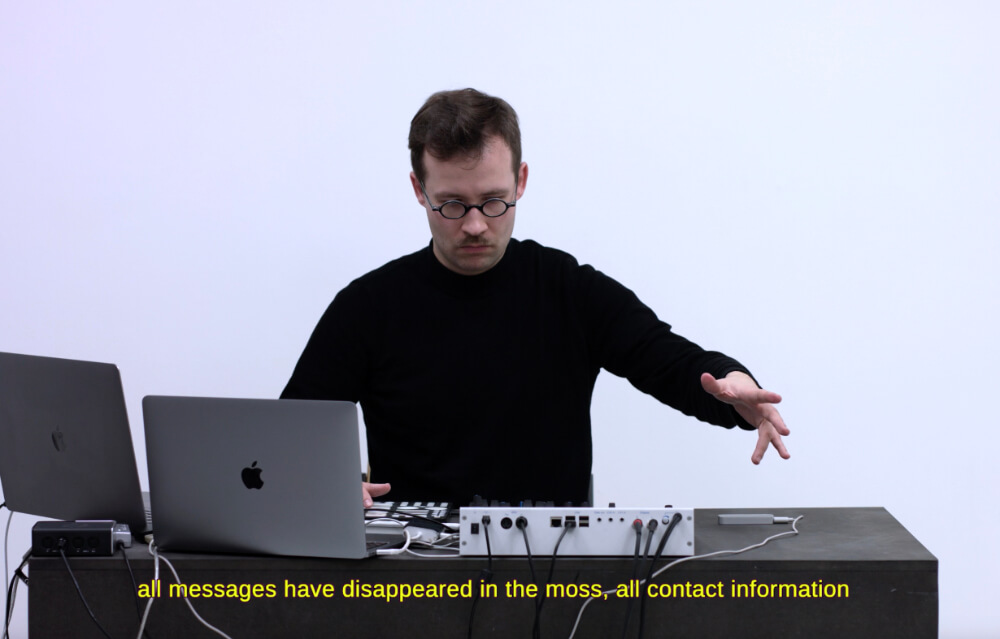

As illustrated in screenshots from the video edition of the work, the human performer plays a hand tracking sensor, which scans hand that is moving in the air. The sensor is connected to a granular synthesizer, which emits recorded human voice fragments and modifies them in real time following notated movements of the performer.

Original sound files consist of a written narrative centered around the theme of technical failure. This narrative is first manipulated sonically by the performer enmeshed in the network of sensor and synthesizer, and then translated by Google Translate from Finnish into English. In the performance, translation application takes its input through the speakers of a computer, thus basing its translation on the actual sound material echoing in the acoustic space. Changes in the intonation and rhythm caused by the performer and sensor are inscribed in subtitles, which end up following the original text sometimes only serendipitously. Among other effects, such as uncanny humour, this brings into view the structural constraints and biases of Google’s linguistic model which is focused on the marketability of singular words, making a questionably large amount of commercial brands appear in the subtitles (Thornton 2019, 153; Maunuksela 2022).

Throughout the composition, accidental and strictly preplanned elements collide into one another. Performer, who follows graphic notation dictating every single movement and position of hand, is in a way doomed to fail, if we understand it as the failure of transmitting information or producing recognizable speech. Failure here turns into a site of intervention, where the processual dramaturgy of machinic collaboration casts aside human-centered dramaturgical ideals, causing a certain sort of obscurity to occur.

Clarity and distinctness were the touchstones of Aristotelian dramaturgy, where the duration and composition of drama were suited optimal for the spectator’s perception. The multilayered, simultaneous and hazardous (dys-)functioning of both human and technical collaborators in Manuaali shifts the focus to the open-ended process of becoming-into-being of the piece at hand. Cathartic purge is postponed in favour of the bodily affects of frustration and melancholy that operate through delays, glitches and ambivalence. The spectator is invited to navigate in the complex field of sensory input, which forces them to recalibrate the means of meaning making along the way.

Expanding technical affordances

Dramaturgy is sometimes referred to as something that is always present in works of art or even in the mode of perception. Still there exists a need to differentiate between works which could be described as “dramaturgy-driven” (Hansen & Callison 2015, 19), and those, where the awareness of dramaturgical mode of thinking stays hidden or unnoticed. Analogously, we could speak about works of art and artistic practices where the role of technology is a productive one, something that not only realizes dreams of the passing technical era but also proposes new ways of perception, even if this is realized through serial failures and experiments without notable outcomes. This requires that the perspective of dramaturgy expands itself from the familiar world of content and narrative and takes into account the technical sphere of production. Moreover, it means a shift from the instrumental and advisory role to a more autonomous position with potential for criticism and intervention, which operates on both conceptual and practical levels.

It is through this sort of attunement that dramaturgy can question the discourse on technology not only in the level of technological narratives, but in the level of use and practices related to technology. To illuminate this idea, let’s consider the hand tracking sensor applied in the piece. Originally known as Leap Motion, this device was released by Leap Motion Inc. in 2016. Although it was developed mainly for virtual reality gaming, it was also hyped up as an innovation that would in near future replace mouse and keyboard. According to the Wall Street Journal, three years later the whole enterprise was sold to a competing agency for one tenth of its former value (Olson 2019). The technical affordances of the hand-tracking sensor didn’t meet up with the expectations for becoming a somatosensory interface in more general use.

In the context of kinetic audiobook performance the failure – relative complexity of the use – becomes the most interesting feature of the device, since it enables us to challenge the tendency of automation in human perception. Instead of making things easier to grasp, the dramaturgical agency of this now-media-archeological hand-tracking device slows down the moment of perception. This turns the reading of the narrator into “attenuated, tortuous speech”, as Viktor Sklovsky described poetry in opposition to the directness and economy of prose in Art as Technique (Sklovsky 1988).

The hypermediacy of the new medium – its materiality and mediality – becomes a dominant element of the kinetic remediation of the digital audiobook. Systematic misuse of technical tools expands their affordances, the possible ways of use embedded in the design. When dramaturgy is sensitive to the accidental or non-linear uses of technology and not focused solely on the predetermined “functionality” of technical appliances, it lays ground for an agnostic and doubtful relationship to technology that acts as an antidote to blatant techno-optimism of the industry. With this in mind, one could state that after all, dramaturgy does not start with a willful step forward, but with a hesitating step aside. It is this movement sidewards that enables us to grasp what is really happening and what makes it unfold the way it does.

Dramaturgical ensembles as agential compounds

Because of this critical and non-affirming tendency, dramaturgy seems to offer a standpoint for handling problems that technicality poses for human consciousness and social organization. In his dissertation On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, Simondon wrote about the kind of knowledge required in the intersection of technical and human worlds. The following passage illuminates this point vividly:

Just as literary culture, in order to constitute itself, needed the wise individuals who had lived and contemplated the inter-human relation with a certain distance that gave them a serenity and a depth of judgment while nevertheless maintaining an intense presence among human beings, technical culture cannot constitute itself without developing a certain sort of wisdom, which we will call technical wisdom, in men who feel their responsibility toward technical realities, but who remain disengaged from the immediate and exclusive relationship with a particular technical object.

(Simondon 2017, 160)

This knowledge position is distanced from the specificities of technics, but still holds responsibility over the translation of technicality into culture and back. Simondon calls this kind of person a psychologist or sociologist of machines, or in lack of existing words, “a mechanologist”. We might also call her a dramaturg.

In the field of performance, a dramaturg is often someone taking care of the dramaturgical aspect of the work or process. The dramaturg focuses on the dramaturgical functions and implications of working with different materials, media and artistic forms. This might be acquired through a fixed professional position or a collective responsibility, depending on the occasion; in any case, it often seems that the perspective of dramaturgy offers a mediating, third space between the work and its makers and the audience. Dramaturgy as practice is enacted in myriad ways, and it partakes and shows up in different phases of process. Still, it can be argued that distance and responsibility intertwine in the character of the dramaturg, who must step aside in order to care.

This also overlaps with the role of researcher and maybe artistic researcher in particular. Distance, understood as personal disengagement and purity of interests, is sometimes associated with the proof of objectivity. Instead, we could see the tuning of the distance as a conscious way of engaging with the ongoing process, that is necessary for preserving the potentiality and otherness of things not yet fully present.

In the working process of Manuaali, I was collaborating with people who had expertise in designing applications and programming electronic instruments. As a dramaturg, I felt the need to distance myself from much of the technical information about techniques applied in the work. This was a form of surrender, mostly a sweet one. It pretty much reminded me of the blurring of details which you need to accept in order to see the outlines of a picture and recognize the underlying patterns below the hassle on the surface.

This need was enhanced by the fact that the piece was transforming every time it was performed. Micromanaging meanings would have been futile; instead of guarding the original text, I felt the need to transpose my authorship as the writer and reader of the text to another level, to the level of dramaturgy. It was only at this level that the inner complexities could be brought together momentarily in the dramaturgical formation of the work. Still, I feel reluctant to call it a triumph of some inventive dramaturgical mastermind, since technical processes of sensor triggered sound modification and speech-to-text translation possess a life of their own. The responsibility of the dramaturg is not to direct, implement or develop their processes to be more efficient, but instead, to recognize how they act in the world – in other words, to grant them a dramaturgical agency.

This agency should not be mixed up with the dramaturgical agency of humans on the stage, characterized by the presumption of intentionality and self-reflection. Different modalities of agency need to be recognized, even when they’re closely tied together. While “automation” refers to self-running action of machines, a more prevalent type of man-and-machine interaction on stage is that of augmentation, where machines are left with the role of support or help, prioritizing the human user as the individual operating technical systems. Another conceptual alternative, that of “heteromation”, refers to a condition where human work is adapted to the functioning defined by machines (Ekbia & Nardi 2017, 32).

Shifts between these three modalities form a dynamic explored in Manuaali. Automated processes and the augmented design are elements in a heteromatic composition, where the dimension of improvisation and free will of the performer are reduced in order to make the human-machine-assemblage work.

Considering this man-made and mixed nature of technical tools and processes, it seems necessary to find a third term mitigating between human and machinic dramaturgical agencies. As the ending line for this presentation, I will propose a concept of “dramaturgical ensemble” for this purpose.

As a concept, “dramaturgical ensemble” draws from the Simondonian notion of “technical ensembles”. According to Simondon, in certain phases of the development of technology, humans no longer act as technical individuals – tool bearers – but are part of the technical ensemble, translating and coordinating the cooperation of different machines. Likewise, we could think that in certain artistic compositions, humans no longer act as dramaturgical individuals possessing a privileged agency, but as part of the dramaturgical ensemble, which combines different elements and units into a heterogeneous whole.

Whether useful or not, as a working term, “dramaturgical ensemble” might offer an insight to the condition, where human no longer acts a sole dramaturgical agent, but instead forms an element in an ensemble of technical and dramaturgical agencies in their different and often simultaneous modalities. The functioning of a dramaturgical ensemble, such as the one depicted with the example of Manuaali, is a constant process of exchange between particles human as well as non-human, which from time to time come together in the act of movement.

References

Ekbia, Hamid and Bonnie Nardi. 2017. Heteromation and Other Stories of Computing and Capitalism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hansen, Pil and Darsey Callison. 2015. Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement. Series: New World Choreographies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Maunuksela, Klaus. 2022. “Kineettinen äänikirja: Kääntäminen esityksellisenä strategiana.” Tiede & Edistys 47(4): 299–316. doi.org/10.51809/te.119938.

Olson, Parmy. 2019. “Leap Motion, Once a Virtual-Reality High Flier, Sells Itself to U.K. Rival: San Francisco startup, which develops and licenses gesture-tracking technology, had in the past been eyed by Apple.” Wall Street Journal, May 30 2019. www.wsj.com/articles/leap-motion-once-a-virtual-reality-high-flier-sells-itself-to-u-k-rival-11559210520.

Simondon, Gilbert. 2017. On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects. Translated by Cecile Malaspina and John Rogove. University of Minnesota Press.

Sklovsky, Victor. 1988. “Art as Technique.” In Modern Criticism and Theory: A Reader, edited by David Lodge, 16–30. Translated by Lee T. Lemon and Marion J. Reis. London: Longmans.

Thornton, Pip. 2019. “Language in the Age of Algorithmic Reproduction: A Critique of Linguistic Capitalism.” PhD diss., Royal Holloway, University of London.

Virate.me. 2022. “Manuaali.” Link to online documentation, accessed October 8 2023: virate.me/manuaali. (Text, dramaturgy, reader: Klaus Maunuksela. Sound design, composition, performer: Walter Sallinen. Visual design: Ville Niemi. Recording: Kaj Mäki-Ullakko. Performance 14.10.2022, Theatre Academy, University of Arts Helsinki.)

Contributor

Klaus Maunuksela

Klaus Maunuksela is a dramaturg, writer and researcher who is currently working on an artistic doctorate in the Performing Arts Research Center (Tutke) in Uniarts Helsinki. The second artistic element of the research, Prosessi (A Process), consists of an experimental novel and a digital audiobook, which will be released in February 2024. Maunuksela’s research interests include translations between sound art and literature, audiobook dramaturgy, materiality of language and sound technology as a medium for narrative and non-narrative writing.