Abstract

In the summer of 2021, after the initial COVID-19 crisis, I conducted ethnographic research in a physical training institution that offered Laban/Bartenieff Movement Studies. The training involved creating and improvising movement sequences, which was a crucial aspect of the program. Due to the coronavirus precautions, eight dancers’ training was conducted in a hybrid format via Zoom. Some dancers attended remotely, while others were present in the studio. In the hybrid setting, limited access to the studio environment and remote intercorporeality resulted in different perceptual fields and coordination dynamics, which impacted the dancers’ creative choices. In my presentation, I will discuss the emerging issues that arose when the dancers improvised as “studio-studio”, “online-studio”, and “online-online” partners. Using an enactive perspective as a theoretical background, I aim to reflect on the outcomes of my fieldwork in the current dramaturgical discussions.

Introduction

In 2015, I studied Laban/Bartenieff Movement Studies (LBMS) at a physical training institution in Berlin. Since then, I have been trying to apply LBMS in my practice and research. Two years ago, in 2021, I conducted ethnographic research at the same institution. LBMS aims to develop somatic awareness by focusing on voluntary bodily movement. Therefore, I thought it would be a great opportunity to monitor the change in bodily consciousness from a dancer’s perspective. I designed my research around how Laban/Bartenieff training shapes the perception of our own body and how it creates a common discourse about bodily experience. To achieve this, I proposed a research design based on a phenomenological approach, which included additional movement sessions with dancers. However, due to the corona measures, the program was held in a hybrid format where some participants were taking classes in the studio, and others were participating remotely via Zoom. This was a dramaturgical shift in my research because during the one-month training, social distancing, absence of touch, and online mediation (Zoom) in the hybrid setting created discomfort for participants and teachers. As a result, I could not apply any of my research plans and had to shift my focus towards the challenges of movement training in a hybrid format and understanding the digitalisation of movement experience. Although the scope of the fieldwork was dancers’ somatic training, improvisation-based movement creations were an essential part of the process and revealed important aspects of dancers’ bodily interactions in creative practices.

In my presentation, I will present the challenges that dancers face while working remotely via Zoom. I aim to reflect on these emerging discussions and relate them to current dramaturgical practices. The main objective is to open discussion on the directions of dramaturgical practices for the digitally mediated remote creation process. To begin, I will look at the concept of dramaturgy from an enactive perspective and mention some of the current dance dramaturgy literature that focuses on enactive cognition. Later, I will delve into details about dancers’ different modes of interaction during their partner-work in the studio and online.

Dramaturgy from enactive perspective

From a broader perspective, I take dramaturgy as an attempt to construct meaning by generating and applying strategies to shape the experience in any art form. The “meaning” that the practice of dramaturgy brings about does not only refer to propositional and discursive aspects. Instead, it encompasses patterns, images, concepts, qualities, emotions, and feelings that constitute the basis of our experience, thoughts, and language (Johnson 2018, 2). I want to introduce enactive “sense-making” here. Sense-making refers to the creation and appreciation of meaning (de Jaegher and di Paolo 2007, 488). This mode of interacting with the world involves actively understanding a situation and determining the appropriate course of action for the agent to take (di Paolo et al. 2017, 121).

When we apply enactive sense-making processes to improvisation and devising-based production-making, two significant aspects come forward. Firstly, enactive theories prioritise the coupling of the sensory-motor system and the environment, allowing us to concentrate on the meaning that arises in the present moment. This highlights the constitutive role of our bodily interaction dynamics and perceptual experience. Secondly, these theories assert that an individual’s sensorimotor abilities are embedded in a broader biological, psychological, and cultural context (Varela et al. 2017). These inferences draw a frame for dramaturgical thinking that emphasises the importance of studying dramaturgy on the perceptual level. This applies not only to the sensorial aspect of production but also to the facilitation of the creation process. In that sense, taking the enactive paradigm as the foundation, I define dramaturgical practices as creating strategies to give direction to our sense-making process, which starts here and now but is embedded in a broader context.

In the field of dance dramaturgy, there are researchers whose works align with the enactive paradigm. Bruce Barton (2015, 182), for instance, is interested in “what a performance is doing, rather than what it is trying to be”. He also takes meaning as a perpetual negotiation between intention and affect. He utilises the term “interactual dramaturgy” to underlie the interactive process of negotiating between explicit meaning and implicit experience that both performers and audience members engage with consciously, intuitively, and instinctively (Ibid.). Phil Hansen (2011) proposes the term “perceptual dramaturgy”. He applies dynamical system theory to facilitate perception and memory for generating creative strategies to work with implicit dynamics of experience in the performance-making process (Hansen 2015). Freya Vass-Rhee (2015) proposes the term “distributed dramaturgy” to explain William Forsythe’s devising-based production process. Her idea of distributed dramaturgy is based on Hutchins’ (1991) “distributed cognition”, which refers to shared mental representations distributed in a sociocultural system. For Vass-Rhee (2015, 90), the ability of distributed cognition is essential in collaborative work since it enables the group to function resilient and flexible like an organic tissue. According to that, in production making, even though group members have their own tasks, dramaturgical responsibility is distributed among members of the creation process. Vass-Rhee emphasises that while the dancers focus on creative potentials in their own work, the dramaturg’s role is to record and track these emerging possibilities. Similarly, Vida Midgelow (2015) also refuses to see dramaturgical thinking only as dramaturgs’ tasks. She indicates that dancers should and can take responsibility for their own practices for dramaturgical possibilities. It is mainly because the necessity of being an outsider and having a distance to creation for a reflective point of view is no longer valid. In embodied cognition, thinking and doing, intellect and the body, procedural knowledge, and embodied knowledge are not two different cognitive modes but intertwined. So, dancers can have a dramaturgical awareness as they improvise. Midgelow proposes improvisational tasks to help dancers develop the modes of attention so that they become aware of dramaturgical responsibilities and respond to them. In that way, she argues that dancers can enhance “dramaturgical consciousness” while performing (Midgelow 2015, 107).

The practices and reflections of these researchers address a clear shift in the notion of dramaturg from being a dramaturg’s task to modes of dramaturgical awareness, which is shared by all participants of the creation process. I will follow this understanding and take dramaturgy as a “mode of thinking” which doesn’t exclude embodied knowledge production and bodily shared-sense making. In that sense, dramaturgy stands in an interesting position which requires certain self-reflective awareness. The awareness of interaction dynamics of the creation process at the perceptual level and the awareness of context where those dynamics and perceptual experience are located and intertwined. Here, it is also important to note the consistent emphasis on intention, attention and awareness in the discussion of dramaturgical practices, which emerged as the most problematic domains in the remote creation process.

In my presentation, I will narrow down my focus to the performers’ experience in the creation process, and I will have a closer look at dancers’ interaction dynamics during the improvisation in a hybrid setting. I will explore how the telematic system, Zoom, challenged their intention, attention and awareness level, which eventually has an impact on their dramaturgical awareness.

Improvising through telematics in three different interaffective spaces

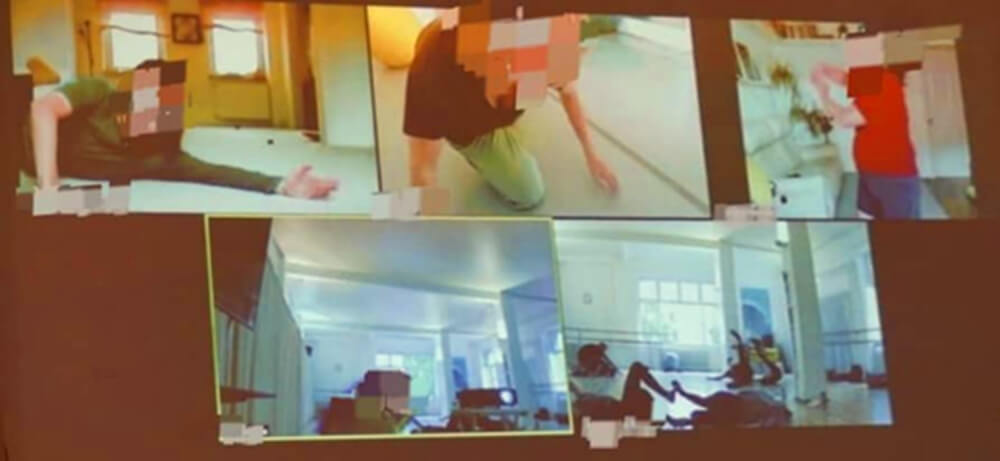

In my fieldwork, training was held in three different spaces, which were connected to each other via Zoom (Figure 1). When dancers get together for partner-work during their improvisation, three modes of participation have emerged based on the pairs’ location: Studio – Studio, Online – Online, Studio – Online.

In each mode, interaction dynamics and movement qualities of pairs during the improvisation were varied. That created diverse spatial and temporal dynamics and also affective qualities that contributed to participants’ meaning-making process and anticipation of it. For Fuchs, the interpersonal sphere generates continuous “interaffective qualities,” which consist of the emotional and affective states of participants, and they can be perceived directly by others (Fuchs 2017). Thus, during the improvisations, three diverse “interaffective spaces” emerged. Now, I want to share some of the differences and notable features of those three different modes in three different interaffective spaces.

Studio – studio interaction mode

During the improvisational dance sessions in the studio, it was difficult to identify common characteristics of the dancers’ interactions as each session produced diverse and varied qualities. However, some features were more prominent than others. For example, the dancers’ use of space differed from other modes of interaction. Despite restrictions on free movement due to COVID-19, couples changed directions, levels, and planes more frequently while moving within their own kinesphere and around their partners’. They were also more attentive to the space created by their partners’ movements.

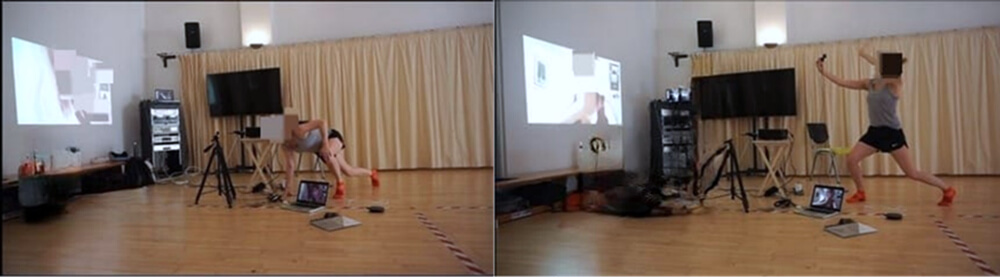

During my observation, the point that particularly caught my attention was how the dancers substituted one sense with another. An example of this can be seen in the attached picture, which is a caption from a video. The couple in the video was improvising on the floor, and they were touching each other’s tiptoes while moving. This touch formed the main thread of their improvisation until the end. However, when one participant changed the position of her leg, they lost touch, and the connection was no longer there. When they lost touch, one of the dancers’ first movements was to lift her head to try and re-establish the touch connection. This was repeated several times throughout their dance, and whenever they lost touch, they looked at each other to find the point of connection on their tiptoes again.

What happens here is basically they substitute touch with a glance; tactile sensorial modality is replaced by vision sensory modality for the accomplishment of intended action. Switching from touch to gaze corresponds to “optimal grip” (Merleau-Ponty 2013; Dreyfus 1996). According to that, our bodies move in the space with a “perceptual attitude” determined by our intention to have the optimal grip of our surroundings (Merleau-Ponty 2013, 316). So, studio participants have more advantages in adjusting themselves to the situation to grasp the maximum. Because they have access to the rich sensorial inputs created by partners’ actions, it is also interesting to think about that in terms of Brian L. Due’s (2021) “distributed perceptual field.” For Due, perception may be distributed, practical, and publicly recognisable by other agents (Due 2021, 135). It means that sensory information provided by others’ actions in certain situations creates a perceptual field; within the same situation, we rely on this perceptual field created by others to construct our actions. It is essential for how we create solutions for new, unexpected situations. And for Due, we can co-operate on perception-related actions regardless of sharing a similar understanding (Due 2021, 153). In the studio-studio mode, it was easy to maintain the relationship since, as partners were moving, they were creating a rich perceptual field through their actions and that became creative possibilities during the improvisation.

Online – online interaction mode

In online – online mode, the main challenge was to maintain the connection between partners. Online participants indicated that eye contact by facing the camera was the primary position and cue to keep the relationship with their partners during the improvisation. Trying to look at the camera not only affected their bodily positions but also had an impact on the “Effort level” of their movement. Here, I use the term Effort for the dynamics of the movement defined by Laban. It refers to energy level and outer expression of inner drives that can manifest in movement in relation to Weight, Time, Space and Flow. According to that, trying to look at the camera gives direct spatial intention to online participants’ movements. While online people were moving in the “Awake State,” which emerges from the combination of Space and Time Efforts, studio people were dancing in “Dream State” (Weight and Flow Effort) or Remote State (Space and Flow Effort). This is to say that studio people were moving with more Flow Effort than online people. It is an interesting outcome because, in the LBMS system, Flow is a motion factor which establishes relationships and communication (von Laban and Ullmann 1988, 76). Laban describes the measurable aspect of the Flow as control and fluency of the movement (von Laban and Ullmann 1988, 77). It means that participants in the studio moved in a way that they had more control and fluency in their movement during the improvisation.

During online coupling, participants had to adopt certain bodily positions to face the camera to maintain their interaction. However, for participants in the studio, eye contact did not appear as the central part of their connection. Instead, they expressed their connection using terms such as “intensity,” “temperament,” “rhythm,” and “attunement.” Some participants even described their experience as “almost subconscious” or “a result of bodily decisions.” These felt qualities that made participants attuned to each other in the studio could only emerge in physically shared spaces. It is because Zoom mediation was insufficient to transmit this level of information to the remote spaces, such as intensity, muscle tone, level of contraction, etc., which generates “interaffective space.” As a result, online participants could not engage each other’s presence in energy level (Effort quality), and they could only keep their interaction through eye contact and their bodily positions.

Studio – online interaction mode

Studio – online partner work brought about discussions on “peripheral vision,” “mutual intention” and “multifocality of the attention” in the interaction process. One of the online dancers noted that in a studio setting, she was able to use her peripheral vision to maintain contact with her partner and understand their movements, even if she wasn’t looking directly at them. However, this didn’t work in the Zoom environment. Her partner in the studio also indicated that she was more aware of other couples in the studio than her partner because even though she kept a Zoom screen on her periphery, her partner was not always in the frame, or only some body parts were visible. In normal studio conditions, eye contact is a clear indication of reciprocal interaction; however, on Zoom, even if the dancers face each other, it does not assure mutual eye contact. Thus, these two modalities of “to see” and “to be seen” were diversified during the partner work and participants needed to be multifocal towards the Zoom screen and the camera.

As a result, creating a “mutual intention” to maintain the connection became much more effortful for dancers. One of the online partners expressed that as follows:

we had to make an effort; the invitation must be very clear for us to notice that the other person is looking for a contact. Otherwise, here we are alone, with no engagement; you have to be clear in your intention; it must be overly stated.

From Merleau-Ponty’s perspective, intentionality is not an intellectual concept and does not always work on a conscious level, but it is also a bodily motor skill which works unconsciously and spontaneously to engage with our environment (Merleau-Ponty 2013). It is also an essential part of the sense-making process. First of all, it is because it constitutes the idea of the autonomous agency who freely chooses to regulate her actions in the world based on her needs or situation (di Paolo et al. 2017, 212). Secondly, the intention of the agency’s action enters the intersubjective realm since it is readable by others. Not only from a phenomenological level but also from a more neural perspective, mirror neuron related research made it clear that our sensory-motor systems can sense the intentions of other’s actions even before the action is completed (Rizzolatti and Sinigaglia 2007; Keysers 2011). Therefore, in the interaction process, coordination between intentional and embodied agents (Fuchs and de Jaegher 2009, 467) makes mutual engagement possible. In training, the studio-online couple struggled with their partner-work because they struggled to sense each other’s intentions.

Conclusion

Here, I’ve mainly addressed the challenges of distant improvisation and interaction. However, my main point is not to degrade remote production and devising processes. Despite the challenges, it is still possible to dance and feel connected remotely, as the studio participant expressed: “[…] And yet, we can dance together even if we don’t see each other; we can still be very close, and we can have a close relationship. Yes, it is different dancing on the screen and dancing here, but still possible […]” From an enactive perspective, the creation process is a shared sense-making procedure, and dramaturgical practices help to facilitate this process, whether it is provided by dramaturg or distributed responsibility. Thus, it is important to understand the underlying mechanism that gives direction to mutual creativity at a sensory level. Our sense-making process is not only determined by physical properties and the context but also created by others’ actions in our environment. Therefore, the dynamics of remote and co-located improvisation are not the same. It is true that one aspect of participants’ discomfort derives from the limited affordances of Zoom mediation. However, dancers indicated that if all participants were online, that would be much easier for them rather than a hybrid format. One of the online participants noted that:

[…] it was just a clash for me […] I would be happier if it was only online. You see people […] and you know what to expect. I could always see gallery people on Zoom; you are all equal […]

What participants experienced as a clash stemmed from the degree of asymmetries, which is much higher in the hybrid format than in the online environment. Emerging dissimilarities in attention, intention, emotional level and differences in interaction dynamics have impacted the co-creation of common meaning among participants in a hybrid format.

In dramaturgical practices, when we work remotely, we can not take telematics as only a channel to transmit information. Zoom and technological devices become more than a mediation because there is no information to be transmitted. As I tried to present here, the information, therefore meaning, is revealed through the use of technology. Participants’ awareness about their bodily positions, attention level, and direction of their intention in the interaction process were revealed while dancing through and with technological devices. So, the telematic system should be considered a training regime for aesthetic innovations, as Klich and Scheer indicate (Klich and Scheer 2011). Specifically, telematic technologies address an epistemological shift in our embodied knowledge generation process because they basically challenge our intracorporeal co-presence, which is the basis of our shared world. So, our dramaturgical question then is not only how we can use these technologies in our production but how we can facilitate the creation process, which can meet the needs of this digital epistemological realm, even though we don’t use such technologies directly in our productions.

References

Barton, Bruce. 2015. “Interactual Dramaturgy Intention and Affect in Interdisciplinary Performance.” In The Routledge Companion to Dramaturgy, edited by Magda Romanska, 179–185. London. New York: Routledge.

de Jaegher, Hanne, Barbara Pieper, Daniel Clénin, and Thomas Fuchs. 2017. Grasping Intersubjectivity: An Invitation to Embody Social Interaction Research. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 16(3): 491–523. doi.org/10.1007/s11097-016-9469-8.

de Jeagher, Hanne and Ezequiel di Paolo. 2007. “Participatory Sense-Making: An Enactive Approach to Social Cognition.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 6(4): 485–507. doi.org/10.1007/s11097-007-9076-9.

di Paolo, Ezequiel, Thomas Buhrmann, and Xabier Barandiaran. 2017. Sensorimotor Life: An Enactive Proposal. Illustrated edition. Oxford, United Kingdom: OUP Oxford.

Dreyfus, Hubert L. 1996. “The Current Relevance of Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology of Embodiment.” https://ejap.louisiana.edu/ejap/1996.spring/dreyfus.1996.spring.html.

Due, Brian L. 2021. “Distributed Perception: Co-Operation between Sense-Able, Actionable, and Accountable Semiotic Agents.” Symbolic Interaction 44(1): 134–162. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.538.

Fuchs, Thomas. 2017. “Intercorporeality and Interaffectivity.” In Intercorporeality: Emerging Socialities in Interaction, edited by Christian Meyer, Jürgen Streeck, and J. Scott Jordan, 3–24. Oxford University Press. doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190210465.003.0001.

Fuchs, Thomas, and Hanne de Jaegher. 2009. “Enactive Intersubjectivity: Participatory Sense-Making and Mutual Incorporation.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 8(4): 465–486. doi.org/10.1007/s11097-009-9136-4.

Hansen, Pil. 2011. “Perceptual Dramaturgy: Swimmer (68).” Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 25(2): 107–124. doi.org/10.1353/dtc.2011.0023.

Hansen, Pil. 2015. “The Dramaturgy of Performance Generating Systems.” In Dance Dramaturgy, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi.org/10.1057/9781137373229.

Hutchins, E. 1991. “The Social Organization of Distributed Cognition.” In Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, edited by Lauren Resnick, John, B.M. Levine, Stephanie D. Teasley, 283–307. American Psychological Association.

Johnson, Mark. 2018. The Aesthetics of Meaning and Thought: The Bodily Roots of Philosophy, Science, Morals and Art. Chicago and London: Chicago University Press.

Keysers, Christian. 2011. The Empathic Brain. Social Brain Press.

Klich, Rosemary, and Edward Scheer. 2011. Multimedia Performance. 2011th edition. Basingstoke: Red Globe Press.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 2013. Phenomenology of Perception. 1st edition. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York: Routledge.

Midgelow, Vida L. 2015. “Improvisation Practices and Dramaturgical Consciousness: A Workshop.” In Dance Dramaturgy, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi.org/10.1057/9781137373229.

Rizzolatti, Giacomo, and Corrado Sinigaglia. 2007. Mirrors in the Brain: How Our Minds Share Actions and Emotions. Oxford University Press.

Varela, Fransisco J., Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch. 2017. The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and the Human Experience. Revised Edition. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Vass-Rhee, Freya. 2015. “Distributed Dramaturgies: Navigating with Boundary Objects.” In Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison, 87–105. New World Choreographies. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi.org/10.1057/9781137373229_5.

von Laban, Rudolf, and Lisa Ullmann. 1988. The Mastery of Movement. Princeton Book Company.

Contributor

Bilge Serdar

Bilge Serdar has a Bachelor’s degree in mathematics education, a Master’s degree and a PhD in Theatre Studies from Ankara University. She completed EU funded Choreomundus – International Master in Dance Knowledge, Practice, and Heritage program. Now, she works as a post-doctoral researcher in the AMBIENT project at the RITMO Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Rhythm, Time, and Motion at the University of Oslo, where she conducts Hybrid Dance Experiments to explore the use of telematic technologies in the artistic creation process.