Abstract

briefly

Between 2020 and 2023 I made a short film WE BITES US (17’ 25”), a hybrid between live action and animation. The cinematography used in the live-action scenes combines two different points of view: that of a cinematographer and that of an autonomous mobile robot equipped with a camera. At times, the robot is controlled by a wearable “prosthesis”, a glove with gyroscopic sensors attached to an actor’s body. There is an element of juxtaposition in the film that shows the tension between a code of cinematic narrative and an unfamiliar “alien” perspective. This paradoxical cinematic apparatus is a techno-feminist gesture to see technological innovation neither as a grand futurist dream nor as a seductively sleek toy for the rich, neither as freedom nor as subjugation.

The film WE BITES US is the main element of the second artistic component of my dissertation: Monstrous Agencies – Resisting Precarisation within the Organisation of Collaboration and Authorship. The research oscillates around parasitic and monstrous relationships with the aim of recognising interdependence. It looks for a way to recombine the power structure of a working environment, conditions, and format, including the human and non-human agencies involved.

about

I will talk about two moments from the making of the short film We Bites Us. We Bites Us is a portrait of the collective: complex, difficult, dark, but also joyful and unpredictable. The film follows a group of rather eccentric, slightly over-intellectualised characters and three fancy poodles, all stuck together in a constantly odding space. What does that mean? That the space is odding? Sometimes the places or situations feel a little familiar, but you can’t say in what way? The purpose, function and appearance are confused and seem somewhat hostile to the bodies inhabiting them. As a result, both the spaces and the bodies are constantly changing, shifting their form. The idea for the film comes from the experience of the post-communist generation faced with the resurgence of the extreme right. It is anchored in the moment of the now, from which the past is still morphing. In the carnal coexistence of “former” people, in the uncontrollable and indecent growth of an unpredictable body, something is still missing. Something is out of place.

Did you spit on it?

Common… Public…Private… Bodily fluids and body parts seem to have life on their own, rebellious, foreign, and unwilling. A group wanders through a monstrous shape-shifting reality; in the grey zone in between life and death, the present and the future, the human, cannibal, and cyborg existence.

Short synopsis of We Bites Us

The film is produced by Kenno Film Cooperative, a feminist production house, so the question of what it means to produce a film based on feminist principles has been with us throughout the process.

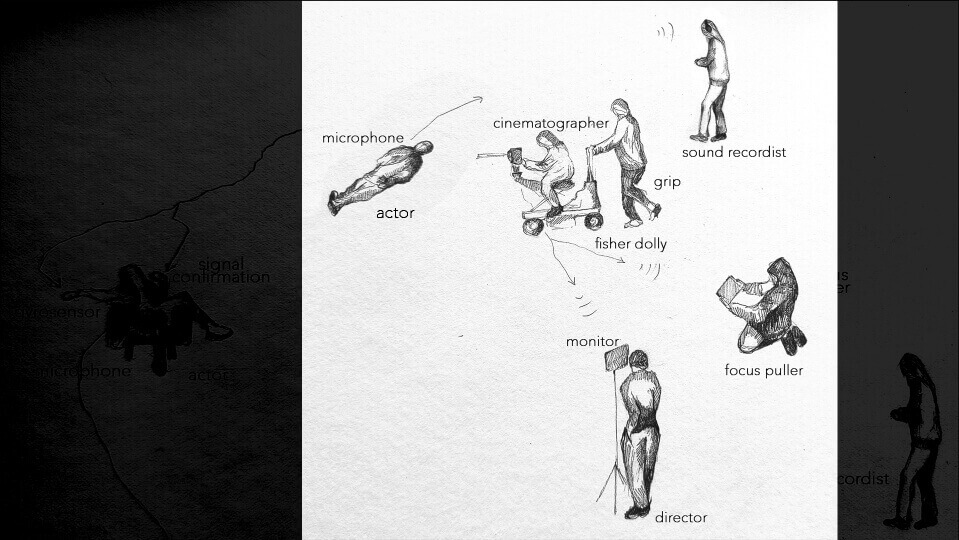

The cinematography used in the live-action scenes combines two different devices: a classical way of shooting with traditional equipment, planned and executed by a cinematographer, Janina Witkowski, and her crew, and another, supervised by the same people, but carried out by an autonomous mobile robot.

the robot at work,

What is an Autonomous Mobile Robot (AMR)? According to Robotnik, the Spanish robotics company, “the AMR is one that, in addition to the initial programming, has a certain degree of independence to make decisions in the middle of the work environment, without the need for human intervention” (Robotnik 2022). Initially, we were looking for a “mobile manipulator”, that is an AMR additionally equipped with robotic arm.

The use of the perspective of such a robot, which is the size of a dog or a small child and is not designed for camera work or as a camera operator, as opposed to the cinema robot arms, which are made for the smoothness and versatility of a panning movement and the precision of a macro shot, was deliberate. It wasn’t only so, that I couldn’t afford the expensive gear, so instead we got this thing, this parody of cinema robots. “It’s just a bloody rumba, only it doesn’t even vacuum” – the focus puller put their impression of the robot into words, after the first day of shooting.

Omron’s LD is designed for transport. It can carry 60–90 kg and can be used as a coordinated fleet of robots, for example to transport the “check-in” trays at the airport. It can operate both in human-free environments, such as automated production halls, and in spaces with a high probability of unexpected encounters with living beings, such as public spaces. It is in the process of product application, being tested for its possible uses, not in mass production. I don’t think the company that loaned it to us really believed that we could offer them a future in the cinema industry, but perhaps it was too much fun not to try.

As we were unable to find a suitable robotic arm as originally planned, the camera was attached to the Omron via a remote head, which allowed additional movement of the camera itself. The remote head was controlled by a joystick, just like the PlayStation. There was a bit of an argument among the crew as to who was going to do the job. The director of photography and their first assistant, the focus puller, both had a go. In the end, the focus puller, Eepu Näsi, who is a passionate gamer, won, so they switched places with the DP on the focus pulling controller.

There was a team of three people from Station of Commons who were needed to organise the process from the technological side. Gregoire Rousseau, who was involved in the process of finding the robot and thinking how to organise the work around it. Then Angelina Barbonelova and Alain Ryckelynck, who coded robots’ movements, tested, developed, and operated it during the shoot. Vesa Virmanen from Omron Electronics, who we found through his former teacher at the Metropolitan University of Applied Sciences, organised the loan of the robot and gave us the basic training and operational information we needed for further development.

the movement of the robot,

What is the logic behind the robot’s movement?

It operates based on a map of a location, which is a kind of scan of a place that it does on its own to establish a working environment. The map is further coded with a series of triggered responses based on location within the map, interaction with an obstacle, or other pre-coded parameters such as speed or duration. It “reads” the environment using lasers and proximity sensors. It follows the path designed for it in the logic: from point A to B in the shortest possible line at a given speed.

It can come close to the moving bodies, but sometimes it gets confused. When it encounters an obstacle, it stops, but sometimes it stops and tries to continue at the same time, which causes a kind of stuttering, and it adjusts little by little until it can continue. Sometimes the robot backs up or turns around, then returns to the previously planned path, correcting it with the knowledge of the obstacle. Sometimes its logic is so precise that it seems irrational and unpredictable to a human sense of mobility.

This, in my opinion, produces an excellent moving image. In general, framing doesn’t follow the actor or the action as a representation or source of dialogue, it’s usually slightly off. It somehow considers the characters in the scene, but also somehow ignores them. In addition, the image shakes, and wobbles because the wheels are not designed to provide the stability that is normally required for camera work.

and then some complications,

In order to trigger a different relationship with the robotic camera movement, I decided to cast a few dogs. The hope was that their presence on the set with the robotic camera would reveal something different about this apparatus than the interaction with somewhat trained actors. However, the poodles… It took these super-smart and super-fast creatures about thirty seconds of barking, a few minutes of suspicious observation from a distance, before they seemed to have the robot figured out. After this initial interaction, they seemed to move on with their lives and acted completely oblivious to the camera’s techno-operator for the rest of the shoot. As we wanted some interaction between the two beings in the footage, we had to come up with a proxy system to provoke it. You can see a fragment of the said footage in the following video.

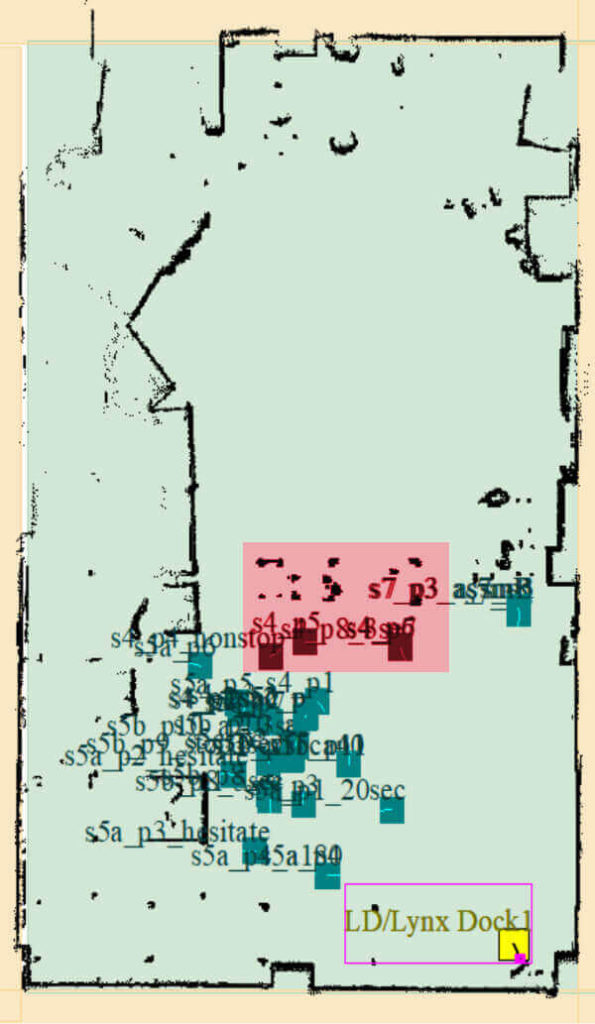

In the following picture you can see the positions of the elements of that scene (marked as red area) within the map of the room. The image is a copy of the map created by the robot.

Each position of the robot has some additional directions and reactions coded. For example, at point s4p5 (scene 4 position 5), “turn slightly to the right” + “repeat three times”, then “wait 5 seconds” before moving to position s4p6.

In the following video you can see a “making of” this scene in the video documentation.

At this stage, I, the director, concentrate on the robot’s path and carry dog treats in my pocket. I walk behind the robot to keep the poodles’ attention. Then the remote head manipulator watches the camera’s viewpoint on the monitor and moves the camera according to the dogs’ movements. The DP, acting as the focus puller, focuses on the image quality and keeps it in focus. So, let’s put it another way: I focus on the robot, the dogs focus on me, Eepu focuses on the dogs, Janina focuses on the image of the dogs. There are some delays in this chain of reactions, because each element, each human/machine or human/animal dependency has a different capacity for speed and rhythm. In the end, what I think the image (the first video clip you saw) becomes is something between focus and loss of focus, reciprocity and detachment, a process of negotiation or a state of uncertainty about who is watching whom.

then more complications…

Perhaps the most technically interesting situation was the addition of the gyroscopic sensors to the technical device described above, in such a way that the actor could control the robot’s movement. With four simple gestures, positions of the palm of the hand, the actor could “call” the robot to move forward, backward, right, left. All these commands are confirmed by an additional button, which also indicates the duration of the movement. Here is some of the footage created with this mechanism.

And here you can see some of the gestures used to set it in motion.

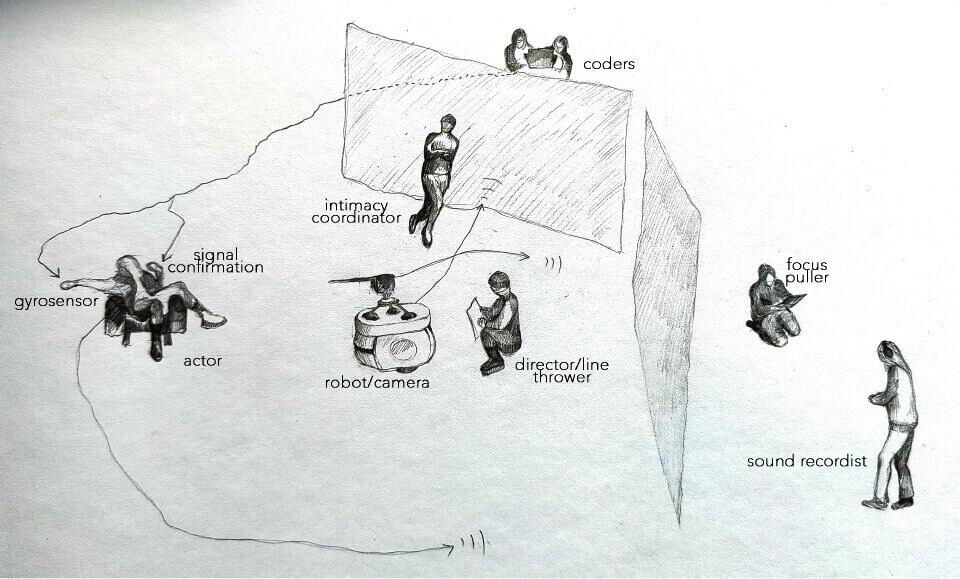

This whole “prosthetic” device was conceived when I was planning this film to have a larger erotic component, a kind of self-erotic encounter between this character and the camera/robot. The idea behind this piece of technology was to change the power structure of the whole crew/actor machine so that the actor could possibly be “alone” with the camera, in control, rather than enacting the erotic situation being viewed by the camera and other people behind the filming apparatus. In the end, the loan of the robot was short, there was not enough time to explore and deepen the relationship between the actor and the robot well enough to feel erotic and to explore all the possibilities of the “prosthetic”device. We went for a softer version of the scene, and this is the organisational structure we ended up with.

The actual situation required a focus puller (Eepu), a sound recorder (Lou Strömberg) and the coders (Angelina and Allan), but because of the remote nature of their work, they could work at a distance, behind the partition, without occupying the direct set of the scene and becoming direct viewers.

An intimacy coordinator (Marit Östberg) with extensive experience in the independent porn industry was present on set They were present during the planning and preparation process, as well as during the shoot, to ensure that the actor did not feel pressured into doing something they did not want to do, given the additional pressure: of time constraints or from the director. So, the intimacy coordinator is there to make things work, safely for everyone, but also in a capacity to come between the actor and the director, to defend the actor from the director’s demands. In the case of this particular shoot, the situation was more complex, and the line of defence was more difficult to find. The dynamic of the entire ensemble was altered.

I (the director) was placed (at the actor’s request) as a line thrower and not “as usual” at the monitor overseeing the result of the actor’s work, so still as an approximation of a viewer/receiver of the scene, but not withdrawn as the ultimate observer or decision maker. The camera, instead of being in the hands of the DP who would follow the plan of the shoot previously agreed with the director, was in this case in the hands of the actor and the plan of the shot was to some extent unpredictable. The actor’s (Vishnu Rajan Vardhani and the Anonymous Stand-In) job was undoubtedly challenging. They had to operate a camera, act in front of it and, due to the intimate nature of the scene, take care to define their own limits in a situation they had never faced before.

I believe that this challenge was made easier, or simply possible, by three factors. The first was letting go of the control of whether the image was satisfactory, simply by deciding that there would only be two takes, and one of them would have to do. The second “easing” was the work of co-designing, with the actors, the robot’s operating apparatus into a few very simple gestures. And the third was to have someone present during the process to ensure that the actors’ needs, agreements and limitations were taken into account before and during the shoot. These three elements gave a sense of control not only to the actors, but to everyone working on the set. No one had ever worked in this way before, so the level of uncertainty, the possibility of failure or things going wrong was high. We put a lot of thought and preparation into making sure that “this” would work and that the sense of uncontrollability would be a positive one. And it did. In a way, it was also this “we” as a structure that worked.

and so, what?

In a way, this device, this “prosthesis” we created was again a mockery of the “classical” cinematographic device. The same “classical” device that we also used for other shots in the film.

This “classic” device is designed to be as precise as possible, to turn a machine that can be controlled by the human hand, to provide tools for the so-called “vision”, so often used in reference to the director’s idea for the film. This machine transforms the “vision” of the human author into a result that can be related to the human eye and mind of the viewer. There is a considerable amount of psychology, understanding and training of human perception that goes into the design of the moving image. And then you have this mockery device that is hyper-controllable, terribly precise, and yet ends up producing random-looking, “accidental” results. Because of its “functional confusion”, what happens is a certain release of tension, or even a repression of the cinematographic process. It is “functional confusion” because it still follows the same logic: the gesture of the hand is translated (by a gyroscope) into the movement of the camera in order to produce representation. The difference is that it doesn’t serve the mind of the one who should decide the framing, but the sense of the one who is filmed. And it doesn’t fulfil the imaginary expectations of the viewer, because it is freed from them by a mechanical logic and a mechanical perspective that doesn’t try to stand in for anything else.

If this shooting strategy was intended as an exercise in human/machine/animal agency, can I call it non-human agency? No. Judging by the amount of work we (many people) had to do to accommodate the robot and the dogs, the human element in it would be called hyper-human or multi-human. I would call it a monstrous agency, one that arises out of the mixture and interdependence of human, machinic and animal elements. And yet this monstrous agency, exercised during the process described above, is less human because the animal and the machine have been given a decisive role in the framing, not a leading role, but a decisive one.

If the shooting strategy was intended as an exercise in parasitic relationships? Through additional “complications”, such parasitic relationships occur through the hijacking of the existing power structure into the chain of dependent functions, which call each other into question. This given power structure is not transformed into a horizontal network of reciprocal exchanges, but into a complex multiple system of dependencies, which, however, allows for some redefinitions and some renegotiations. By using the reconstruction of what already exists, the “cascade”, a unidirectional chain of parasitic relations, a “semiconduction” of the flow of the power (Serres 1982, 5), by repeating them with a slight tweak, a twist, a “mockery”, we obtain a different flow of the feeding structure – the strange material itself, the twisted logic of its production and productivity.

References

Robotnik. 2022. “What is an AGV and differences with AMR?” Accessed November 16, 2023. robotnik.eu/what-is-the-difference-between-agvs-vs-amr/.

Serres, Michel. 1982. The Parasite. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Contributor

Karolina Kucia

Karolina Kucia is a performance artist with a background in sculpture and intermedia as well as in performance studies. At the moment she is also doctoral candidate in the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki. She develops organizational scores based on concepts of parasite, monster and slip in the context of precarisation of labor in post-neoliberal capitalism and the current form of art institutions.