Abstract

This essay discusses aspects of the composition KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE (2022) by Norwegian composer Trond Reinholdtsen. I explore an idea of a principally unrestricted musical material formulated in a presentation text related to the work and discuss its relation to the artistic research project that commissioned the work, Reinholdtsen’s practice, postdramatic theatre (Lehmann 2006) and the Norwegian concept of likestilt (“equalized”) dramaturgy. KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE was commissioned by pianist Ellen Ugelvik and percussionist Jennifer Torrence as one of nine premieres in their artistic research project Performing Precarity (Ugelvik et al. n.d.). I argue that some of the texts surrounding this work may themselves be understood as performative and thus as practical instances of an idea formulated in one of them about a principally unrestricted material in music.

The opening lines of a text presenting the Norwegian composer Trond Reinholdtsen, published on the website of the German contemporary music festival ECLAT in February 2022, claims that this composer at some point in time decided that his creative practice should include all imaginable materials and art forms:

Composer Trond Reinholdtsen decided a few years ago that his practice would include all art forms, that music is more than sound, that there should be no restrictions on the type or relevance of material [.]

(ECLAT 2022)

My research as a Ph.D. candidate in performance practice at the Norwegian Academy of Music aims to both explore and challenge this idea of a principally unrestricted material, as well as its relation to a context referred to as musical (“that music is more than sound”). In my dissertation I am planning to discuss a selection of musical and theoretical examples that in different ways engage with this idea. I am educated in musicology and subsequently in creative writing and visual arts. In this essay, it is primarily the musicologist who speaks.

In the paper I presented at CARPA8, I particularly aimed to discuss how the idea of a principally unrestricted material might affect traditional functions of musical scores and musical writing. The composition that the above sentences about Reinholdtsen are written to present, entitled KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE, served as my example.

From attending the rehearsal process of this piece prior to its first public performance, my paper argued for the need to understand a musical score as a function more than a given format, a function somehow regulating a division of labour between composing and performing with the help of musical writing. I further proposed to approach musical writing from a similarly functional perspective. An immediate example of the latter that would differ from a conventionally produced musical score, would for example be a prerecorded sound or video file played back as part of a live musical rehearsal or performance. KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE contains several such files, recorded by the composer before or during the rehearsal process.

This essay builds on my conference paper. However, as the scores and the documentary video that were part of my conference presentation are not yet cleared for publication, I will instead use selected publicly available verbal texts surrounding the composition KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE as point of departure for developing some of the theoretical frameworks that my paper also explored. Some of the texts I will discuss might be understood as paratexts (Genette 1997) with a defined function in contemporary music as institutional practice. I will however try to show how some of them might as well be read as performative. If so, they might also be understood as examples of practical instances of composing with a principally unrestricted musical material.

The initial quote could be seen as connecting two paradigms in the Western art institution: a differentiation in disciplines and an understanding of artistic practice, including music, as autonomous and free. Proposing a principally unrestricted material could be understood as applying the last paradigm to the first – apparently allowing a principle of freedom to dissolve disciplinary and material differences between art forms. Historically, such an idea is of course not new. Ed McKeon for example traces a similar paradigm shift back to American composer John Cage’s (1912–1992) late work, arguing that it implies “a reconfiguration of music’s “internal” and “external” relations, its essence and autonomy, as constitutive of claims to musical value.” (McKeon 2022, 11) Just as McKeon argues about Cage, disciplinary differences are not erased completely in the above case of Reinholdtsen’s music either, as the word music remains in the equation.

The above claim that “music is more than sound” might as well be understood as valid for any music, if music is conceived as resulting from collisions and interactions between human and nonhuman bodies and material agencies. This calls for discussing how an idea of a principally unrestricted material might influence specific examples of creative practice.

KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE was commissioned from Trond Reinholdtsen by its two main performers, pianist Ellen Ugelvik and percussionist Jennifer Torrence, as one out of nine world premieres in their artistic research project Performing Precarity taking place between 2019 and 2023 (Ugelvik et al. n.d.). Performing Precarity aims to rethink the idea of mastery as guiding principle of professional contemporary music performance. The performers describe their project like this:

To be a contemporary music performer today is to have a deeply fragmented practice. The performer’s role is no longer simply a matter of mastering her instrument and executing a score. Music practices are increasingly incorporating new instruments and technologies, methods of creating works, audience interaction and situations of interdependence between performer subjects. The performer increasingly finds herself unable to keep a sense of mastery over the performance. In other words, performing is increasingly precarious.

(Ugelvik et al. n.d.)

This need to rethink mastery could be seen as a principally unrestricted material reflected from a performer’s perspective. As such, it has precursors within music performance such as violinist Anna Lindal’s work on unlearning performance (Stockholm University of the Arts n.d.). In postcolonial studies, a field that as contemporary music is negotiating traces of modernism, albeit in different ways and perhaps for different reasons, Julietta Singh has published a book called Unlearning mastery (Singh 2018).

All the works commissioned as part of Performing Precarity were expected to somehow relate to the above statement that “performing is increasingly precarious”. In other words, for a composer, accepting a commission in this project implied (as accepting commissions normally does) a certain limitation to an imagined unrestricted creative autonomy as indicated above. How to relate to the theme of performing precarity was up to each composer.

The title KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE translates as «No ideas, no new perspective». Before the work was finished, the composer knew that its first performance was planned to take place at Festival ECLAT, a festival for contemporary music located in Stuttgart, Germany.

It is possible to argue that a principally unrestricted material is present already in how this title plays with negating the obsession of «the new» that tends to ride contemporary composed music as institutional practice, and that may perhaps be traced back to ideas of musical modernism. As a title, KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE could be read as a statement telling the festival and its audience that modernism is over, and consequently that creating something new is fundamentally impossible. Such a reading implies an extension of the score to the website of the festival, as the title starts discussing its context and the conditions for its own existence with a future audience long before they are seated in the concert hall. Both claims are as well reflected materially in the piece.

At the same time, KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE adapts to the institution in practice, showing up and doing its job as a world premiere in a festival for new music. A principally unrestricted material is unquestionably also present in its “instrumentation”, listed in a manner imitating contemporary music practices that mainly compose with sound, and where the selection and constellation of instruments are an important part of the compositional process:

KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE (2022)

(ECLAT 2022)

for Ellen, Jennifer, emergency instruments, ghosts, floating instruments, lyrics, rain samples, modernist-nostalgic-neoclassical revival video documentary, the Blob, various degrees of darkness and choir.

In Reinholdtsen’s practice, such a multimodal material can be traced at least back to the turn of the millennium. In this period, I worked as a producer and festival organiser in the field of contemporary music. In that role, I commissioned and followed the development of new work by composers and performers. In 2001, on behalf of the local department of the concert promoter Ny Musikk[1] in Oslo, I commissioned a new piece from Trond Reinholdtsen that became the work Turba: Theories of Mass Society, premiered at the Ultima festival in 2003 by the Norwegian Soloists’ Choir. Turba is Latin for crowd. In music, the word appears in passions or oratorios, referring to situations where a choir as a group moves the biblical story forward, in contrast to parts where a choir reflects or comments on events. Turba: Theories of Mass Society among other things included live spoken monologues by singers in the choir, a live performance lecture by the composer videostreamed from backstage of the concert hall, and a section where the conductor invited the audience to join in singing the hymn An die Freude from Ludwig van Beethoven’s 9th symphony (1824). None of these elements were however specified in our commission, whose guidelines were 12 professional singers and a traditional mixed choir layout (SATB).

Large parts of Turba: Theories of Mass Society are collected in one and the same musical score (unpublished). This document however leaves out central parts of the live performance, such as the verbal manuscript for the performance lecture or the series of slides projected on the back wall. Some of these elements not present in the score are documented in a review in the online music magazine ballade.no (Korbøl 2003).

In the role of producer and festival organiser I argued for ideas behind future works in applications for financial support, facilitated communication between composers and performers, organised and attended rehearsal processes and was involved in the choice of venues for first performances. When my practice later expanded to the performing arts, I was fascinated to learn that my experience with unfinished work and with processes preceding first performances, had a more specific name in contemporary theatre and dance: dramaturgy. The term seemed to be shared by artists and scholars alike. I appreciated how dramaturgy may refer both to material composition, “the shaping and composing on stage of materials and devices in time and space according to aesthetic principles” (Larsen 2019, 40) (my translation), and to practices of building knowledge, language and publicness around such doings. One motivation for bringing my research on a principally unrestricted material in music to a conference on dramaturgies, is that I aim to explore correspondences and differences between musical and dramaturgical perspectives. I am interested in how ideas of a principally unrestricted material are pronounced across artistic disciplines, and whether differences and similarities are discernible in creative practice.

One apparent similarity exists between the idea of a principally unrestricted material in music and a term established both in creative practices in the performing arts and in theatre and dance studies in Norway called likestilt dramaturgi, or an “equalized” dramaturgy. This term refers to a dramaturgy where the action and the work inherent in the word dramaturgy might in principle be taken on by any element on a stage – visual, sounding, physical or verbal. Likestilt dramaturgi was developed by theatre scholar Knut Ove Arntzen to describe practices in Scandinavian project theatre in the 1980s (Arntzen 1990), and has been developed further by Wenche Larsen into a tool aiming to differentiate between various types of action in a given play and how they interact (Larsen 2019). However, does “principally unrestricted” imply equalized?

One apparent difference is not located between music and dramaturgy but between a principally unrestricted material in music as pronounced above, and theatre scholar Hans-Thies Lehmann’s term postdramatic theatre (Lehmann 2006). The term postdramatic refers to how the contemporary theatre practices Lehmann aims to discuss, tend to challenge the central organising function of written dramatic text, a function that could also be understood as a privileged or dominant position:

[…] postdramatic theatre establishes the possibility of dissolving the logocentric hierarchy and assigning the dominant role to elements other than dramatic logos and language.

(Lehmann 2006, 93)

The postdramatic is as well developed to avoid the literary bias of the postmodern and the tendency to understand it as an epoch. Lehmann aims to include “the presence or resumption or continued working of older aesthetics, including those that took leave of the dramatic idea in earlier times, be it on the level of text or theatre” (Lehmann 2006, 27), and the last paragraph in his introduction is entitled Tradition and the postdramatic talent with a nod to T. S. Eliot.

The initial statement of a principally unrestricted material in Trond Reinholdtsen’s creative practice may resemble Lehmann’s postdramatic move. However, while postdramatic theatre aims to reflect a dissolution of hierarchies between dramatic and non-linguistic theatrical devices, in a context of scored music this translates to dissolving hierarchies between the sounding and the non-sounding: “Music is more than sound”.

Correspondingly, consequences of a principally unrestricted material may affect the functioning of a musical score differently than the functioning of a theatre manuscript. The two function differently in the first place, but they may also decentralise and give away authority in different ways. In KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE for example, a principally unrestricted material neither leads to the score being dissolved nor to the score being made equal to other musical devices. Instead, scores become more numerous and more materially different.

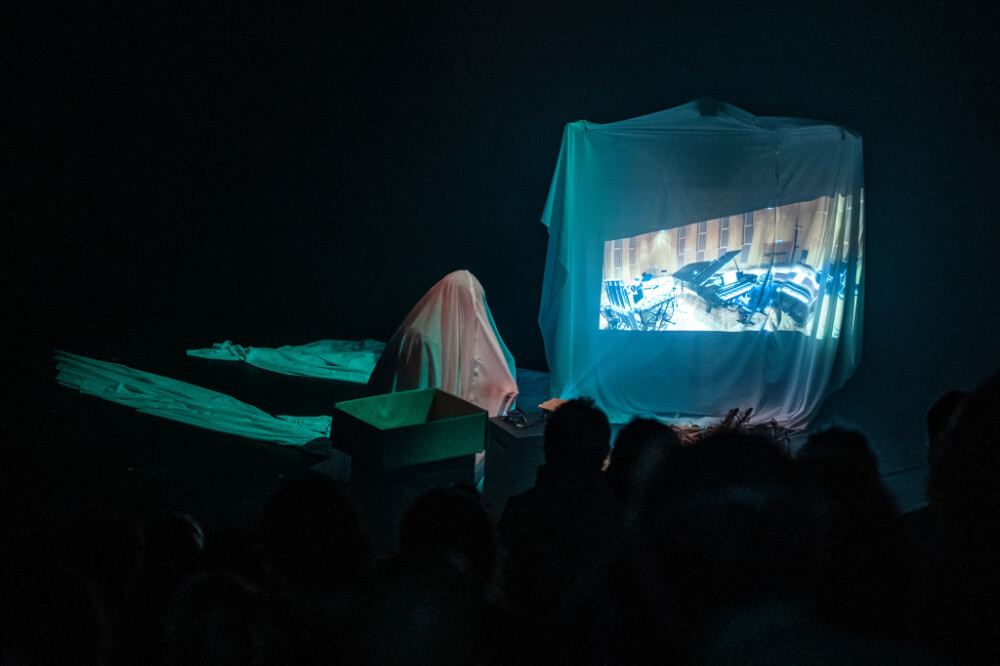

One instance of a score in KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE that differs materially from a conventional one, but whose function could be understood as a form of musical writing, is the above-mentioned documentary video recording, referred to in the instrumentation of the piece as “modernist-nostalgic-neoclassical revival video documentary”. The video and its sound were recorded separately during the rehearsals of the piece and afterwards put together. The video shows Ugelvik and Torrence in a rehearsal space at the Norwegian Academy of Music, dressed in everyday clothes and performing a dense musical score for percussion and keyboard instruments, as captured in this documentary photo taken by the festival’s photographer.

The presence of this video recording on stage (I will get back to the ghosts!) connects both to the title KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE and to the commissioned theme of performing precarity. To an audience familiar with 20th century music, combining piano and percussion points to a body of work composed in the second half of the century by composers such as Béla Bartók (Sonata for 2 pianos and percussion, 1937) Karlheinz Stockhausen (Kontakte, 1960), Luciano Berio (Concerto for two pianos and orchestra, 1973), Bruno Maderna (Concerto per due pianoforti e strumenti, 1947–1948).

When I heard Ugelvik and Torrence record the music to the video during rehearsals, I assumed the music consisted of short musical quotes from repertoire like the above. It turned out to be wrong, as the music they recorded was a score by Reinholdtsen, composed in a style of postwar repertoire for percussion and keyboard instruments. A video recording of original music performing a style is anyway the statement from the title of the piece returning in a new modality, reminding us that modernism is gone.

Or, perhaps modernism, or its spectre, has returned, both in the ghosts on stage and in the stylized composing? The spectre of modernism a known trope[2] [3], which the ghosts in KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE anyway challenge by being living ghosts.

The closed format of the video also connects to the theme of performing precarity by the fact that Ugelvik and Torrence never play their instruments outside the video recording. A grand piano and timpani are present on stage, but with one coarse exception, the performers never play them live. The restricting of conventional musical mastery to the rehearsal space and the video format refuses to locate the precarious performing elsewhere – for example behind the white linen covering the two musicians throughout the whole piece, making them invisible and visible at the same time and severely restricting their vision and possibility to move.

The initial presentation text about Trond Reinholdtsen is longer than quoted above. After a relatively neutral opening sentence that could have been written by the festival, it continues in a way that seem to break with a conventional curatorial statement:

Composer Trond Reinholdtsen decided a few years ago that his practice would include all art forms, that music is more than sound, that there should be no restrictions on the type or relevance of material – resulting in an “aesthetic of universal genius-dilettantism.”

(ECLAT 2022)

The combined omnipotent ambition and indecisive judgement performed by the three words “universal genius-dilettantism” open for an alternative reading where the composer himself is writing in third person about his own practice with the festival website as his performance space. Besides pointing to the fact that composer biographies or artist statements are normally collectively produced, such a reading opens for understanding the above text as a performative work with such texts as a genre, and thus as an act of composing with a musical material that is “more than sound”.

While the quote about Reinholdtsen’s practice claims that music is more than sound, a postdramatic perspective however claims that music is a sounding instance of something theatrical. Lehmann underlines that a postdramatic perspective might as well be directed towards a dramatic text, emphasizing its theatrical, nondramatic aspects. Perhaps paradoxically seen from a disciplinary perspective, whenever such aspects imply sound, Lehmann refers to them as both purely theatrical and musical:

Even where great directors use dramatic texts but emphasize the nondramatic, purely theatrical aspects about them, it is not least of all the musicalization which most strikingly manifests the otherness vis-à-vis the dramatic theatre.

(Lehmann 2006, 92)

In Nekrosius’ work musicalization manifests itself especially in the relationship between humans and objects on stage. The latter undergo a perversion of their function, they are used as musical instruments and interact with the human bodies to produce music.

(Varopoulou in Lehmann 2006, 93)

Lehmann’s and Reinholdtsen’s two instances of the word music do not exclude each other. But compared to the tensions at work in KEINE IDEEN, KEINE NEUE PERSPEKTIVE between affirmation and negation, work and genre, original and style, presence and absence, text and paratext, recurring modernists and living ghosts, I will argue that despite structural and performative similarities between what a principally unrestricted material in contemporary music and the promotion of wordless elements in postdramatic theatre could be said to do, there are still disciplinary differences between the two. These differences however become clearer when temporarily juxtaposed and compared. To continue such disciplinary comparisons is the purpose of my further exploration of this topic.

Notes

1 The Norwegian section of the ISCM.

2 Audience present in the theatre space or watching the broadcast could also see and hear that each part of the video recording was introduced with reference to Samuel Beckett’s monologue Krapp’s last tape (1958) thus to a piece working with time through recording, in which the lonely Krapp once a year adds a new recording to the earlier recordings of his own voice – and to modernist theatre.

3 Even the materially oriented Lehmann describes an unresolvable connection between the postdramatic and the dramatic in almost spectral terms: “This describes postdramatic theatre: the limbs or branches of a dramatic organism, even if they are withered material, are still present and form the space of a memory that is ‘bursting open’ in a double sense.” (Lehmann 2006, 27)

References

Arntzen, Knut Ove. 1990. “En visuell dramaturgi: De likestilte elementer / A Visual Dramaturgy: Equivalent Elements.” Katalog vol. 1 1990 – et saernummer av SPILLEROM, tidskrift for dans og teater, 8–21.

ECLAT Festival 2022. “ECLAT | Performing Precarity II.” Accessed 7th December 2023. www.eclat.org/en/konzert/performing-precarity-ii/.

Genette, Gérard. 1997. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Literature, Culture, Theory Series (20). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Korbøl, Aksel. 2003. “En mangfoldig og flott konsertopplevelse.” Ballade, October 13th, 2003. www.ballade.no/kunstmusikk/det-norske-solistkor-en-mangfoldig-og-flott-konsertopplevelse/.

Larsen, Wenche. 2019. “Likestilt dramaturgi.” Teatervitenskapelige studier (3): 39–54.

Lehmann, Hans-Thies. 2006. Postdramatic Theatre. Translated by Karen Jürs-Munby. London; New York: Routledge.

McKeon, Ed. 2022. Heiner Goebbels and Curatorial Composing after Cage: From Staging Works to Musicalising Encounters. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Singh, Julietta. 2018. Unthinking Mastery: Dehumanism and Decolonial Entanglements. Durham: Duke University Press.

Stockholm University of the Arts. n.d. “‘Unlearning performance’ – fragments and doubts by Anna Lindal.” Accessed 8th December, 2023. www.uniarts.se/english/research-and-development-work/research-projects/unlearning-performance-fragments-and-doubts/.

Ugelvik, Ellen, Jennifer Torrence, and Laurence Crane. n.d. “Performing Precarity.” Research Catalogue. Accessed 8th December, 2023. www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1040522/1054989.

Contributor

Hild Borchgrevink

Hild Borchgrevink is a research fellow at the Norwegian Academy of Music with a project exploring dramaturgical approaches to post-instrumental music. She holds an MA in musicology (University of Oslo) and an MFA in Art and Public Spaces (Oslo National Academy of the Arts). She studied performative criticism in Stockholm and creative writing in Bergen. 2012–2017 she edited the magazine Scenekunst.no. Alongside her Ph.D. she teaches musicology at UiB and curates Public Art Norway’s project STUDIO at KMD in Bergen.