In this narrative I describe and reflect upon some features of a dance and theatre research process in which I participated during 2011. The participatory performance Who Are You – Breath, Steps, Words and Other Things? was a collaboration between dance-scholar, dance artist and choreographer, Dr. Leena Rouhiainen; lighting designer and researcher Tomi Humalisto; sound designer and researcher Antti Nykyri; videographer and dance artist Riikka-Theresa Innanen and the writer of this, actor and scriptwriter, whose part was funded by a grant for artistic work of the Arts Council of Finland. It was produced by the Training Theatre and the Performing Arts Research Centre of the Theatre Academy in Helsinki and The Academy of Finland, and performed in December 2011.

Who are you – was a participatory performance, or a performative installation environment that was based on experimenting with somatic and psychophysical methods of elaborating the performers’ sensibility in the now-moment. It was a collaborative process, and also a postdoctoral artistic research project, part of Dr. Leena Rouhiainen’s Academy Research Fellowship, funded by The Academy of Finland. (Rouhiainen 2012b) Facilitation, improvisation, and solos as well as duets with movement and speech were worked on during the entire process and later formed scenes in the performance. The performative installation environment was based on spatial dramaturgy where videos and sound were of great significance; they had a role as (interactive) scenographic elements, as the visitors could come and stay as long as they pleased, and leave when they wanted. (Kinnunen et Rouhiainen 2011)

The main collaborators in the making of the performance were Rouhiainen and the writer. From the very beginning we started to question in practice, how to develop shifting modes of awareness of the performer. In this contribution I focus on our practice-led exploration, following my own research interest: transformation through breathing and voice in the work of a performer. I draw from the experiential material of the process and utilise my personal notes, as well as other inspirational resources. (Barba 1995; Bosnak 2007; Linklater 2006; Reznikoff 2004/2005; Vuori 1995) As I problematise the human perception of time and space, I refer to sociologist Robert Levine (Levine 2006).

To join in this collaboration sounded exciting and challenging. We shared an understanding of the importance of somatic and psychophysical methods in the artistic work of the performers, as well as an interest in exploring the demands that a contemporary performer/ dancer/ actor faces in her professional working environments. Leena’s research interest was influenced by Reichian body psychotherapy and somatically oriented dance, whereas my orientation was practice-led by various actors’ psychophysical methods, of which I focused in this project on methods of breathing and voice work.

Led by the Practice

My personal reflections about our practice stem from my interest in the use of actors’ practical breath and voice training methods, as well as the basics of harmonic, or meditative, chanting and improvisation, and understanding of how the voice vibrates and thus affects the human body. (Vuori 1995; Reznikoff 2004/2005; Utriainen 2005) Through the adaptation of these interests into our work I wanted to approach the phenomenon that can be called an awareness of the now-moment in artistic practice. Specific layers in participatory, or collaborative contemporary performing, such as acting without a role or encountering visiting participants beyond a conventional theatre event, became focal points for my reflection, related to the daily collaborative, non-hierarchical space.

I discuss a few experiences that are part of the complex skills and abilities a contemporary performer needs, as she works with changing groups, environments and tasks, and collaborates with professional artists from various backgrounds. I end this narrative by suggesting a practitioner’s meta-level orientation for collaborative work, which differs from the Western, modernist tradition where the actor, or artist, is generally seen as an independently operating, self-conscious member of the group.

A Dance of Tasks

Our artistic interest lay in creating an atmosphere of playfulness and meditation where the visitor-participants would ask themselves or others: Who are you? We wanted to offer a multisensory, aesthetically affecting spatial experience. As performer-participants Leena and I would guide the audience through a variety of spatiotemporal scenes. There would be no fixed roles for us but a dance of tasks, from playmates to performing soloists, from facilitators to breathers-in-space. For this, an extra daily orientation would be essential, what Barba describes as an “alteration of balance [of energy]”.

Furthermore, our intention was to develop soft and smooth ways of working, without purposely pushing and exhausting our bodyminds. Our challenge was in combining meditative bodymind exercising with the work of dancers and actors. Our experiential understanding was that whatever our bodies contained and carried from rehearsal to performance, would affect the participants.

PICTURE: blue ribcage, strictly framed yellow and red

These quick drawings are pieces of my notes and actual experiences of the 22 June and the 24 October 2011. They were sketched when we were about to start rehearsing. In the first one I chose the colour blue to describe the feeling in my body. The focus is on the ribcage, legs are just simply sticking out. In the other one the torso is also strictly framed, the arms are thin. Through the drawings I recall my momentary body image. It looks stiff and I am easily reminded of that embodied sharpness, a tense feeling in my body. As notes from moments of awareness, they still seem to work much better for me than any words.

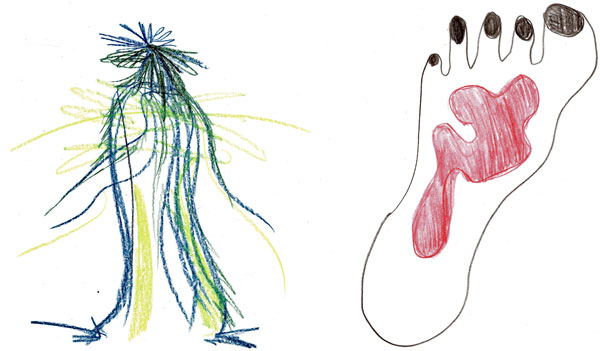

PICTURE: airy hairy, sole of a foot

These sketches show how I felt by the end of the rehearsals. Yellow and green lines spread on the paper like loose hair in the wind. Does it not look a little like a shaman? To me it speaks of the warm, careless and strong activation needed in that session. The footprint brings me back to our grounding exercises: silent, slow walking began a process that finally lead to an experience of a focused existence in a hot spot of flesh, grounded, towards the floor.

We did these drawings every day at the beginning and the end of the practice. They were a part of our psychophysical and somatic preparatory work, and were useful for reflection. They help me also now, afterwards, to trace momentary changes in the daily practice. With them I return to how my awareness of time, space and situation altered, and how I benefited from conscious breathing while rehearsing.

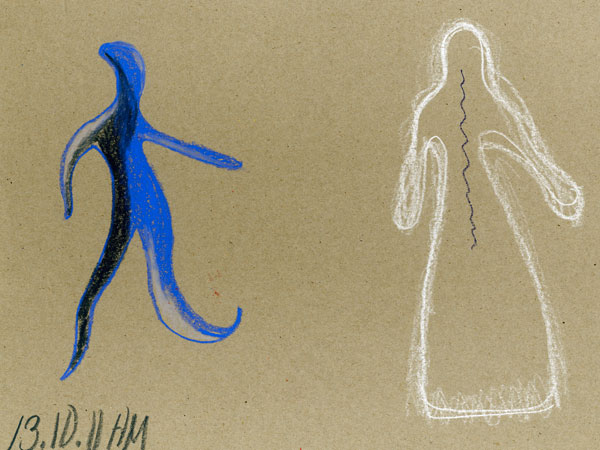

The bluish pair of drawings bring back the moment of transforming an everyday way of being – busy, heady, with a wandering mind and a stiff body, feeling cold – towards a more flexible position: sensuous, warm, slowing down, breathing with the space around me. The drawing about the beginning reminds me of my need to resist schedules which organize an ordinary day. The frame of the body draws the boundaries between an individual and the environment around her. The body is still though aware and active.

Theatre anthropologist and director Eugenio Barba writes about the demand for the performer to attune from daily into extra-daily attitude while working:

“The body is used in a substantially different way in daily life than in performance situations. In the daily context, body technique is conditioned by culture, social status, profession. But in performance, there exists a different body technique.” (Barba 1995, 15)

According to Barba (1995,17), extra daily techniques mean an orientation on stage that wastes energy with maximum effort, and is opposite to daily techniques. He draws examples from Asian performing arts and their visibly different qualities; he “imprecisely translates” the most important principles into European understanding: energy, life, power and spirit.

The performers’ extra daily orientation in Who are you – has both similarities and differences with Barba’s view. Our aim was not to present an intense performance which would catch the spectators’ collective attention for their entire stay, but to create an altering awareness of the performers, where it would be possible to let go of the extra daily qualities. It would then be possible for the visitor-participant to let her own activity and awareness guide her in the space.

Time Frames

Sociologist Robert Levine (2006) has analysed how cultures live and understand time differently, and how these understandings meet and collide when people travel and settle down in new cultural systems. There are parallels here with artistic practice, for example in the forming of temporary groups. Stepping into an artistic process can cause both good and bad cultural shocks. Levine’s primary terms: clock time – event time, describe the shift in the experience of time that we were working on and wanted to offer to the visitor-participants of Who are you – Breath, Steps, Words and Other Things?

According to Levine, clock time is scheduled, filled with routines and linear thinking. In a clock time culture preciseness is highly valued. When a clock time inhabitant steps into an event time culture, her experience of time is sharpened: she notices that things are not functioning the way they do at home. She may experience that time is wasted or stretched.

As I understand it, event time contains a freer attitude towards lived reality; it allows spontaneity, chaos and reorganising, whereas clock time builds on preciseness, coordinated structures and predictability. When clock time culture is carried within a practitioner in artistic work it may become an obstacle. It is however important to keep in mind that there is no short cut to help one free oneself from a profoundly learned discipline of timekeeping; it is usual that lots of energy in stage work is “wasted” in the struggle to free the vitality of performers.

Barba describes the body-mind character of artistic work:

“Creative thought is actually distinguished by the fact that it proceeds by leaps, by means of a sudden disorientation which obliges it to reorganize itself in new ways, abandoning its well-ordered shell. It is thought-in-life, not rectilinear, not univocal.” (Barba 1995, 88)

In our process, we concentrated on the performers’ sensations, observations and embodied modes of awareness, and drew elements into the performance from these.

To experience the process of moving from a daily way of being to calmness, in order to concentrate on a psychophysical exercise, I must make a shift. It may resemble the shift between clock time and event time. It enables a slowing down and release; I open up to the emerging situation. My drawings tell their stories: they are about turning one’s focus towards the situation and the other(s). The pictures remind me of a diversity of modes of being in time and space in the rehearsals.

PICTURE: filled with blue/ white frame with spine

As I dialogue further with the drawings they bring me back to an in-between space, to a threshold where my awareness finds ways of action within the now-moment.

In contemporary projects a performer shares transformational dimensions of her work with her partner-in practice; with the group or the spectator. Postdramatic or applied theatre and performance bring the contemporary performer into unpredictable situations. The performer’s capability of sharing her ideas, sensations and space become focal in these new forms of performance. (Lehmann 2006; Oddey 2007)

All experimental performance work questions the traditional roles of the genre and offers new ones: the facilitator, the co-performer, and the co-participant, to mention a few. Different kinds of positions of the performer, and the spectator, create different options to solve the questions of space, action, interaction, intensity and expression. The contemporary stage as a whole is in motion. Contemporary theatre projects suggest a dance of answers to the questions posed.

Numminen (2011) describes the openness of the contemporary theatre. She argues that its focal question is in “being otherwise, or seeing otherwise”. Contemporary theatre and performance is thus not a pure genre of the performing arts, but it wants to provide actions and motion that put the stage into a dance of representations, interpretations or means of expression.

Returning to my notes: each pair of drawings gives a view of the elements included in the daily rehearsals; the creation of a freely breathing, interactive awareness; an expanded experience of time and a mindful interaction. These are the elements that we discussed would be essential and they were present in a changing balance in our rehearsals. Mindfulness in a performer’s artistic practice can mean being conscious of her actual methods of participation, but it can also include a non-hierarchic quality of authorship in artistic work. Mindful attitude demands empathic listening and trust, thus it offers multitudinous, sensitive ways of practice. (Kinnunen et Rouhiainen 2011; Tarvainen 2008)

After the shift from the clock mode of being and thinking to the event mode and beyond to the liminal, it became possible for me to approach the other participant(s), and to create a consciously shared awareness in the artistic practice.

Our aim was to begin each rehearsal without much planning, from our own bodymind condition experienced that day. We found that our extra-daily orientation started best with drawing, slow walking, breathing exercises, deep body alignment and voice work. There was a mutual understanding among us about the demands of proceeding further in the creative space. I call it a space for embodied and collaborative imagination (Kinnunen 2008, 138; Bosnak 2007). The event time quality enabled us to reach for deeper modes of practice; into a lively but calm awareness which relied on opening oneself up instead of controlling and knowing. We were aware that the journey would require trust and would take us through not knowing, through an expanded experience of time and space, to an entity that could be called a performance where the spectators could be invited to participate.

Step by Step

After drawing, our working days started with breathing and walking. First we did slow walking: we simply moved the weight of our bodies from one sole of the foot to another, at the same time observing the sensations of the body. We did this for five to eight minutes. After that we proceeded into applications of Reichian breathing exercises introduced by Leena, or other breathing and vocal exercises introduced by me. (Rouhiainen 2012b; Vuori 1995; Linklater 2006) From there we often proceeded into experimenting with body resonances; sensing the inner space with vibrations of our own voices, and listening to the resonances in the outer space and the other participants. It was my recognition of the dynamism of an air pillar which made me appreciate the significance of voice work for our aims. Together Leena and I developed variations and combinations of these exercises from day to day.

After quite a time of preparatory practice, simple exercises of observation, movement improvisation and improvisation with words led us further into the work. We regularly paused to describe our sensations, talk about our perceptions and suggest the next moves. All these activities were linked to a very sensuous way of collaborating without losing openness and imagination. Thus we step by step created the performative installation environment whilst we also little by little asked the other group members to join in the discussions and the practical sessions. For example the videos of the breathing corner of the performance were drawn from our pre-performative work. Riikka-Theresa observed our practice, which was then discussed, after which we chose the elements for the video.

The meaning of our practise revealed its full significance in the performative event. When the visitor-participants came we were ready to witness their possible attunement to the space but we were very insecure as to how they would do this – would they agree and play with us, or would they behave otherwise, maybe leave all the possible activities untouched?

In the comments and reflections of both the visitors and the members of the artistic group, several described an experience of the disappearance of time. Our group organised two opportunities to hear the comments of the visitors (Recorded discussions 13 December 2011; 18 January 2012). Both times there was a lively discussion about individual experiences, observations, encounters and aims. Some of their comments gave an impression that certain features of the event resembled those of an insight in meditation, whilst others invited a socially active playfulness. Every visitor-participant more or less made individual choices about different possibilities. Some spectators were critical about having felt that they were forced to perform as if they were on stage during their partaking into the activities.

Breathing as a Method

Conscious breathing is essential according to several (or all) methods that aim at increasing or changing the performer’s abilities in mindfulness, is the performer an actor or a shaman or something else. (Linklater 2006; McAllister-Viel 2009, 115–30; McDaid 2009, 131–46) Breathing exercises offer multiple possibilities to transform one’s embodiment. It is a well-known fact that misuse of the body and the breath cause malfunction of our whole organism. Malfunction consists of muscular tension and unconscious movement habits that lead to reduced bodily wellbeing. (Wolf 2009, 57)

But breathing is more than this. A collaborative performer’s specific concentration on breathing makes a re-orientation to her own body and the environment possible. Levine’s sociological terms, clock time and event time, point out the differences in tempo-spatial integration in different cultures. Clock time demands precision, planning and efficiency. It is common to us who live in Western societies. Event time oriented societies can be seen as careless, unworried, easygoing. I chose to use this pair of terms in this reflection because they give value to the social connotations of the now-moment; a freely breathing lively way of being that enjoys discussion, acting slowly or instinctively and wasting time by not knowing. At the same time it is clear to me that a performer-collaborator’s task goes beyond sociological criteria; the basics of the practice lie in giving discerning attention to awareness.

PICTURE: swirls/ air pillar

Exploring Through Breathing

Leena and I shared an interest in developing our work as artist-researchers. It concerns both our professional skills and the abilities that contemporary performing artists need in order to work in various environments and to provide theoretical and methodological discussion on issues concerning contemporary performance. The practice of breath formed a basis for our work. It affected both our individual awareness and the shared space.

After orientating myself into conscious breathing, I found it easier to be a facilitator, actor, collaborator, mover, or writer-in-performance. Freeing the breath through spine and diaphragm exercises (Linklater 2006), restoring the breath (Nair 2007), working with the vibrations of the voice (Vuori 1995) and applications and combinations of those formed the basis that I introduced into our daily practice. Barba (1995) following Decroux, states that “killing the daily breathing” and using conscious breathing provides the dynamism needed in stage work. Conscious breathing activates and softens a tensed body and helps to focus a distracted mind. Although our means of exercising were gentle, we ended up in extremely long sequences of breathing, movement, resonance and interaction.

Elaborating scores of breathing actions through our sensuous findings allowed further embodiment and mindfulness. In my journal I wrote:

“A breathing exercise offered a moment for listening to my body that day, for noticing its weight, tension, tiredness, restlessness, or: lightness, joyfulness, playfulness, excitement. It gave the opportunity to give way to what my body wanted: to relax, to stretch, to lengthen the exhale, to sink deeper into my body, to sense the air, to find the air container, to hum.” (Kinnunen 2011, working journal)

Finding the air container in a breath and voice exercise offers a way into deeply concentrated voice work. The now-moment was fostered by a dance of exercises that led us to experience the resonance of the human voice. We formed simple, natural scales of sounds which made us aware of our inner space and linked us with the sound we could hear from the others. The sounds massaged our inner organs and uncovered areas in our bodies that needed more focus in order to resonate well. (Reznikoff 2004/2005; Vuori 1995) After these activities the experience of standing, walking, moving and (inter)acting was different from everyday standing and moving; I was filled with liveliness and imagination, a container of spirit, sensitivity, energy and air, a dilated body. (Barba 1995)

Sensitivity and Embodied Imagination

A condition of collective embodied imagination is maybe the best description for my experience of the awareness that was essential to the artistic process of Who are you – Breath, Words, Steps and Other Things? Collective embodied imagination describes the opening of the performer towards the other, the unknown and the unexpected. Embodied imagination means an embodied awareness that cannot be controlled, but it can be fostered and observed.

Embodied awareness enhances the use of one’s senses and thoughts and so can lead to greater use of the imagination. It can also lead towards the partner(s)-in-practice. I wrote in my journal:

“In today’s performance we noticed how easy it is to improvise the order of our solos and duets. […] A visitor-participant took part in my solo in the twister area. The feeling of surprise was pleasant. It was enjoyable to allow a sudden change in the score. A visitor stretching her hand toward me and joining the moment was like a gift.” (Kinnunen 2011, working journal)

When the embodied imagination starts to activate, it also opens up one’s memory. It exposes elements of oneself that one normally keeps private or is unaware of. The collaborators balance between emerging aspects of the collective as well as of the individual. Great amounts of sensitivity and empathy are needed in this vulnerable, fragile work.

I have already mentioned that actor education and theatre literature mostly consider the work of performers as individual professional practice. In the contemporary performing arts, this is not enough; there lies an unexamined territory of co-embodiment within true collaboration. Performers have always known that the sum of the group members’ work is more than the individuals can ever elaborate by themselves. Further exploration of the transformative potential of collective embodiment will lead to greater understanding of this phenomenon. As the Jungian psychotherapist and theorist Robert Bosnak (2007, 11) underlines, embodied imagination is not about intelligent thinking, nor about creating fiction. It is bodymind action, like dreaming, where collective images become embodied, real.

A Meta-Reflection

I have described here aspects of a flexible, sensitive way of attuning to collaboration. As I reflect upon the working process, I see that a great deal of the ideas for the performative installation environment developed during the rehearsing – not in earlier planning, nor after the rehearsals. This thought has significance to me as a performing artistic researcher. It underlines the necessity of giving way to transformation-in-experiment, intuitive choice, implicit understanding and a shared bodily basis.

Now-moment oriented artistic collaboration demands specific professional skills and thoughtful action. The collaborators rely on their former experience, are self-reflective and self-directed, and they bring their capability of interaction with them to a shared working culture.

Collaborators work in a complex environment which consists of negotiations, agreements and visions. Their respons(e)ability lasts until the last performance is over, in a research context much longer. They create much of the environment themselves and they conduct the whole of the process together. It demands emphatic listening to oneself and to the collaborators. (Kinnunen et Rouhiainen 2011; Rouhiainen 2012b; Tarvainen 2008)

Awareness of the Now-Moment

Leena and I have investigated the influence of our artistic training on our practice. The aesthetics and discipline demanded from a traditionally trained actor or dancer do not always help in contemporary artistic inquiry; we needed to understand these influences before we could truly experiment.

PICTURE: one-eared/ my body is all ears

Settling down in the now- moment, scanning our bodies by various means – that was how our practise started day after day. But the most important thing was not what we did but how we did it.

The aim of our artistic process was to create a participatory performance that would benefit from specific reflective somatic and psychophysical means. Our deeper aim was to create a performance and an artistic process based on the mutual creative influence of the members of the artistic group. Finally, our wish was to create an environment that would also be activated through the activities of the visitor-participants. We were realising a long-term dream of creating a meditative atmosphere in a performance that would give the audience choices of moving freely and constructing their own (artistic) experience of it, like the studio-stage was changed into a gallery, or an ordinary activity (e.g. walking) was transformed into a mindful activity and one’s daily awareness into an extra-daily way of being. Our dream was to give the visitors the choice of adopting whatever role they wished: a spectator, visitor, co-actor, co-dancer, observer or something else.

There are innumerable ways of making performances within the contemporary performing arts. Postdramatic theory and practice of theatre provide radical possibilities for thinking about participatory artistic events as non-dramatic and the role of a performer as a non-performer. (Lehmann 2006; Numminen 2011b; Oddey 2007; Smith et Dean 2011) The variety of practices that formed the participatory parts of the spatial dramaturgy in Who Are You – Breath, Steps, Words and Other Things? were fostered during and from our rehearsing. Likewise were born the performers’ parts. Our rehearsing developed our performer-facilitator’s consciousness and helped in altering the activity needed in the performing situation. The task to move from one role to another proved enjoyable. Although I was nervous before the first visitors came, I was convinced within my bodymind of that our work could be shared and that made me trustful.

In this essay I have discussed a piece of non-dramatic artistic research. I am arguing for practice-led research within the performing arts that encourages more conscious ways of creating shared theatrical spaces which touch both the artist and the visitor on unexpected levels. I especially point to the little known territory of the performer’s empathic awareness and the urgent need for a holistic understanding of collective embodiment. So part of the future of the theatre is a collaborative approach that uses material from the now-moment experience of the performers and visitors instead of fiction-making through the traditional rules of theatre and drama. Thus it would take part in construction of an empathic, responsible environment for encounter and experience within art. This creates an empathic environment in which art can be encountered.

Bibliography

Barba, E. (1995). The Paper Canoe: A Guide to Theatre Anthropology. London: Routledge.

Bosnak, R. (2007). Embodiment: Creative Imagination in Medicine, Art and Travel. London: Routledge.

Kinnunen, H-M. (2008). Tarinat teatterin taiteellisessa prosessissa. (Stories in the Artistic Process of Theatre-Making) Acta Scenica 21. Helsinki: Theatre Academy.

Kinnunen, H-M., Rouhiainen, L. (2011). “Approaching Embodied Respons(e)ability: Explorations in Mindful Interaction.” Lecture-demonstration at The Politics of the Psychophysical Symposium, Theatre Academy Helsinki, Helsinki, November 16–17.

Lehmann, H-T. (2006). Postdramatic Theatre. Abingdon: Routledge.

Levine, R. (2006). A Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist. Oxford: Oneworld Publications.

Linklater, K. (2006). Freeing the Natural Voice: Imagery and Art in the Practice of Voice and Language. London: Nick Hern Books.

McAllister-Viel, T. (2009). Dahnjeon Breathing. In J. Boston & R. Cook (Eds.) Breath in Action. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 115–130.

McDaid, M. (2009). Transformative Breath. In J. Boston & R. Cook (Eds.) Breath in Action. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 131–146.

Nair, S. (2007) Restoration of Breath: Consciousness and Performance. NY: Rodopi.

Numminen, K. (2011b). Johdanto (Introduction). In A. Ruuskanen (Ed.) Nykyteatterikirja: 2000-luvun alun uusi skene. (The Contemporary Theatre Book: The New Scene of the Early 21st Century) Helsinki: Like.

Oddey, A. (2007). Re-Framing the Theatrical: Interdisciplinary Landscapes for Performance. NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ouston, J. W. (2009). The Breathing Mind, the Feeling Voice. In J. Boston & R. Cook (Eds.) Breath in Action. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 87–100.

Reznikoff, I.(2004/2005). ”On Primitive Elements of Musical Meaning”, JMM: The Journal of Music and Meaning 3, [www.musicandmeaning.net/issues/showArticle.php?artID=3.2], sec.2.3.

Rouhiainen, L. (2012b). From Body Psychotherapy to a Performative Installation Environment: A Collaborating Performers Point of View. In S. Ravn & L. Rouhiainen (Eds.) Dance Spaces: Practices of Movement. University Press of Southern Denmark.

Smith, H., Dean, R. T. (2011). “Introduction.” In H. Smith & R. T. Dean (Eds.) Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh University Press.

Tarvainen, A. (2008). Empathetic Listening: Toward a Bodily based Understanding of a Singer’s Vocal Interpretation. [www.runko.net/dokumentit/empathetic-listening.pdf]

Utriainen, J. (2005). A Gestalt Music Analysis: Philosophical Theory, Method, and Analysis of Iegor Reznikoff’s Compositions. Jyväskylä: Jyväskylä University.

Wolf, J. (2009). The Art of Breathing. In J. Boston & R. Cook (Eds.) Breath in Action. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 57–67.

Vuori, H-L. (2011). Hiljaisuuden syvä ääni. (The Deep Sound of Silence) Helsinki: Unigrafia.

Unpublished

Kinnunen H-M. (2011). Working journal.

Recorded discussion with the audience after the performance on 13 December 2011.

Recorded discussion in the research seminar of the Performing Arts Research Centre of the Theatre Academy Helsinki on 18 January 2012.