This chapter offers a doctorate-level introduction to a series of challenges and benefits involved in interdisciplinary dance research that is (co-)led by an artistic researcher. Strategic approaches are shared, the importance of methodological choice-making is discussed, and the relationship between such choices and the impact of the knowledge produced is emphasised with reference to examples from the author’s research praxis (inserted throughout).

Risks and rewards

As in all other forms of interdisciplinary research, projects that cross dance artistry, scholarship, and science are more time-demanding and tend to be less recognisable to stakeholders and assessors than projects that are defined within the norms of one specific discipline. The outcome of the research can also be less stable and predictable. In other words, this kind of work involves a significant risk of failure to produce results that are considered valid by and useful for specific research fields. If we flip the coin, however, this risk is also what constitutes the exciting, innovative, and original potential alive in this work. By finding ways of crossing fields of knowledge, negotiating methodological standards, and having one’s blind spots revealed again and again through questions raised from the perspective of another discipline, researchers are pushed to exceed their knowledge and advance past the boundaries of what can be imagined within a single discipline.

In my experience, successful crossing and negotiation demand that challenges of communication, methodology, reach, documentation, feedback or transfer, and articulation are addressed with rigour. When that is done explicitly and within a strong research design, the risks initially mentioned can be turned into opportunities. The loss of a single, stable disciplinary field can be replaced with multiple fields, effectively expanding the impact of the work. The problem associated with accessing resources, typically reserved for discipline-specific knowledge production, can be addressed by sharing resources collaboratively. Most importantly, however, is the fact that interdisciplinary work has the potential to address questions, problems, and phenomena that are too complex to be understood using the methods of one discipline alone.

There are many strong examples of dance research conducted across dance practice, dance studies, and dance psychology or science. Dance scholars Dee Reynolds and Matthew Reason, neuroscientist Corinne Jola, and their team’s phenomenological and scientific research into the effect of music on audience reception of dance is a strong example (Reason et al. 2016); so too is neuroscientist Guido Orgs, dancer Matthias Sperling, and their research team’s scholarly and scientific study of the pleasure audiences take in watching joint action in dance (Vicary et al. 2017). An advanced analysis of joint action in Forsythe’s choreography, which scholar and dancer Elizabeth Waterhouse, dancer Riley Watts, and dance scientist/psychologist Bettina Bläsing collaborated on, integrates scientific knowledge and observations with theoretical, scholarly concepts, and the embodied knowledge of dancers (Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing 2014).

Although dance artists and their perspectives are very present in these studies, the explicit focus of the studies is on scholarship and science, not on artistic research. Choreographer Wayne McGregor’s long-term collaborations with neuroscientist Philip Barnard and cognitive ethnographer David Kirsh come closer to a meeting between equals: Categorisations and analyses of McGregor’s praxis that were produced by the scientists have been repurposed collaboratively and in artistic research to develop choreographic language and a dance training program. These developments maximise and further develop the usage of cognitive strategies revealed in the initial research (May et al. 2011; Kirsh 2011; deLahunta, Clarke, and Barnard 2012; Callaway 2013).

For the purpose of anchoring the strategies of this chapter in interdisciplinary project examples that feature artistic research and that I have privileged access to, I have chosen to draw on two research topics of mine: 1) The dramaturgy, psychology, and performativity of performance generating systems, and 2) The demands that ageing dancers experience and the strategies they develop to meet them.

Communication and the performativity of articulation

The first obstacle and opportunity that is encountered in cross-disciplinary work is communication. Even basic terms like ‘research’ can vary significantly in meaning. For Canadian choreographers, early stages of rehearsal are referred to as ‘research’ regardless of whether they involve inquiry; for a dance scientist, ‘research’ requires a hypothesis, research design, and ethics protocol. Both uses of the term are correct. To collaborate, however, these individuals will need to adopt more specific terms, such as ‘exploratory creation phase’ and ‘experimental intervention’ that can explain the processes involved. The need to explain, demonstrate, and name the aspects of a praxis, a subject matter, and a research approach that your contribution brings to a collaborator is time-demanding, but it also brings about an opportunity to gain clarity about those aspects for yourself. Such clarity is perhaps the primary precondition for successful interdisciplinary collaboration. Without that clarity it becomes very difficult – if not impossible – to locate points of connection, overlap, or transfer between the disciplines.

Embodied knowledge in dance can be implicit (i.e. it may not register consciously) and artistic inquiry is often concerned with the emergence and discovery of something that cannot be defined or known up front. Indeed, articulation of tacit knowledge may be part of an artistic research objective and not the entry point. That said, the starting point of artistic research is usually known, as are some of the questions, curiosities, source materials, challenges, movement approaches or tasks, spaces, and technologies that are involved. Some of the methods that artistic researchers wish to explore in their attempts to render the implicit explicit in process may also be known, while others are sought out and developed in response to these starting points. It is possible to name and explain such aspects at the outset, while noting that some of them remain subject to change if the research process is emergent and iterative. In doing so, choices tend to become clearer, as does the understanding of when certain choices need to be made and in response to what.

In 2014, Christopher House, the Artistic Director of Toronto Dance Theatre, returned to Deborah Hay’s solo score I’ll Crane For You in preparation for public performance. I observed this work in progress and recorded several interviews with House. In 2015, we co-authored an article on the notation of the work (Hansen with House 2015), and in 2016, we co-taught a course and experimental intervention for scientific testing on the same topic at the University of Calgary. House’s adaptation of Hay’s score is one out of five systematic improvisation scores I was studying in order to examine how they generate dance in performance and how their built-in tasks, rules, and source materials affect the dancer(s) psychologically. I refer to these improvisation scores as ‘performance-generating systems’ because their components are predefined and the interactions between these components that generate performance thus tend to be systematic.

In Hay’s works, a practice of continuously taking in fresh information, responding to it in movement, and letting go while inhibiting planning is combined with a series of score tasks that range from the abstract to the concrete. There is also a framework for rehearsal that prevents planning and rote-learning yet matures the dancer’s mental capacity to sustain the kind of hyper-presence the work depends on. These components were fairly easy to inquire into and articulate as they were explicitly available to House. Questions about how the combination of these components generates performance and how it affects the dancer were much harder to answer because this knowledge was implicit.

I was working with three social and natural scientists (behavioural economist Robert Oxoby, experimental psychologist Vina Goghari, and – in a follow up study – educational psychologist Emma Climie) in order to observe implicit effects that do not register phenomenologically to the dancer and thus are highly difficult (in some cases impossible) to access using the more subjective research methods of artistic research and scholarly analysis alone.

Part of our objective was to develop tools to notate the generating components and their effects so that other dancers might re-engage them. Because this notation approach would need to be responsive to our developing insights into implicit knowledge, we were unable to articulate the notation approach up front to our collaborators and funders; instead, we articulated the activities and steps that the research would progress through:

- Interviews about the generating tasks and source materials of the system. The interview questions were to be based on rehearsal observations.

- Artistic, self-reflexive observations about challenges and solutions arrived at during rehearsal.

- Qualitative analysis of self-organised patterns of response that appear across four recorded evenings of performance with attention to aspects drawn from steps 1–2 and Dynamical Systems Theory.

- Translation of these discoveries into shortcuts for notation and teaching.

- Application trial of the shortcuts with a group of advanced performing arts students in an intensive course.

- Test of the effect on cognition and learning of participation in this course using standardised working memory and cognitive flexibility tests as well as qualitative coding of the participating students’ daily observations of challenges and solutions.

- Revision of the notation, implementing our findings.

In steps 1–3, House and I needed to develop a shared language for Hay’s and House’s practice, for his subjective experience, and for the components of a dynamical system. In steps 4–5, we needed to synthesise and translate this insight to a language that is accessible to someone without our shared vocabulary and understanding. During steps 5–6, I furthermore needed to explain to the three collaborating scientists the basic principles of the system and how I hypothetically reasoned that the hyperpresence and multitasking involved could affect the participants. In return, the two scientists explained why only part of these hypotheses could be tested scientifically and listed the test conditions required. The conversations I had at step 5 with scientists were not possible to have at step 1. When arriving at step 7, practical implications of the highly specialised psychological findings had to be considered and articulated in an accessible form.

Articulation can facilitate interdisciplinary collaboration, even when it feels premature. The concrete nature of that which has been articulated helps others consider it and factor in the conditions that it depends on in the research process. Articulation is thus performative; it places your contribution in the worlds of your collaborators and invites them to work with it. It also carves out something that feels smaller and perhaps more diminished than the less explicit potential embedded in a process. I have found that a useful way to ensure that this early articulation supports process and does not merely lock it into the already known is to work towards some degree of shared understanding of the different types of knowledge and methodology at work.

Different knowledge paradigms

The primary challenge associated with interdisciplinary work is that of negotiating different kinds of knowledge. Instead of adopting a naturalised attitude towards the research norms of your own field, it is useful to consider the concept of knowledge paradigms. In the 1960s, Karl Popper argued for the scientific falsification principle. The idea was that research projects should be repeatable and transparent. A peer should, in principle, be able to replicate all conditions and procedures of a past study and either arrive at the same result or prove the results false. This approach understands knowledge as a puzzle: add and test individual puzzle pieces and researchers will eventually be able to map everything that exists positively (Popper 1999). The contemporaneous Thomas Kuhn reacted with a counter-perspective, which has been as influential over time as Popper’s scientific falsification principle. In simple terms, Kuhn looked at how foundational ideas have gained and lost influence over history and argued that such ideas produce shifting knowledge paradigms. That which is considered valid within one paradigm is typically critiqued or regarded as invalid within another, and thus knowledge is not believed to be falsifiable or accumulate over time, but rather paradigm-dependent. According to Kuhn, a knowledge paradigm arises when an idea gains support because it can explain something or get at phenomena in ways that the existing paradigms cannot. When that happens, other researchers set out to prove the new idea right until the limitations of these attempts prompt a new idea that gains support (Hacking 1999, 219–24).

When we, as researchers, apply popular theoretical concepts to our research in dance, we are effectively reconstituting the truth value of the paradigm that such concepts represent. Hermeneutics, structuralism, cultural theory, postmodernism, constructivism, embodied cognition and enactivism, as well as the post-Anthropocene are all examples of shifting paradigms that have influenced dance research and continue to do so. Although the sciences may seem like they are in a time-gap of perpetual positivism and continue to operate with Popper’s view on knowledge, it is not difficult to identify different periods with dominating ideas and methods affecting research in scientific disciplines. Take a moment to think of examples from psychology like the shift from Cartesian and computational models of a mind that controls the body, through behaviourism with its attempts to shape human beings culturally via positive and negative conditioning of reflexive responses, through to the more contemporary theory of embodied cognition that views all mental capacities and responses as dependent on the body. Paradigmatic transitions between dominating ideas can also be observed within positivism.

Methodology and criteria of validity

Each paradigm poses more or less explicit ideas about the existence of phenomena (i.e. its ontology) and closely related theories of how phenomena can become detectable to the researcher (i.e. epistemology). A methodology is comprised of ontology, epistemology, methods, and tools. Although the ostensible differences between research collaborators from diverse disciplines is manifested in different terminology and the usage of different research methods and tools, those all reflect more fundamental ontological and epistemological differences, which are best understood in the context of their respective theoretical and paradigmatic foundation.

One of the main reasons why ontological and epistemological differences matter, especially when crossing artistic, scientific, and scholarly research in dance, is that they inform the different criteria of validity of the involved fields. In the following examples, the typical ontologies and epistemologies of four paradigms are offered alongside a discussion of the different criteria of validity that often apply to them.

If a positivist position on ontology is adopted, as dance scientists often do, the researcher accepts at a foundational level that phenomena in the world exist in and of themselves. The work of the researcher is to objectively measure them and their causal relationships while minimising the effect this activity has on the phenomena studied. From such a position, validity does in general depend on whether the instruments used can produce reliable measures of the phenomena and whether all of the factors that might significantly affect the phenomena have either been considered or eliminated. The significance of the effects or relationships measured tends to be calculated with reference to the law of statistics, which again reflects a positivist ontology. The more generalisable the results, the higher their truth-value and utility (see Bernard 2013 for an accessible introduction to the criteria of validity involved in scientific experiments). The research team does not want to know what the effect of, for example, a medical treatment may be depending on the perspective chosen, they wish to know what the effect is most likely to be in the largest possible number of cases.

When the researcher chooses the relative ontology, which is common to paradigms from hermeneutics to cultural studies within the humanities and social sciences, then phenomena in the world exist through complex relationships and such networks of relationships include the researcher. It follows that the epistemology is interpretive; the researcher needs to interpret how, for example, collective meaning, patterns of behaviour, or forms of social organisation are produced, maintained, and reflected in objectively observed and subjectively experienced relationships. Just as the phenomena studied become something different in various relationships, the researcher’s interpretations will also differ depending on how he, she, or they relate and which relationships they examine. In this case, validity depends on factors such as: the consideration of the researcher’s own bias; the data types collected and their ability to reflect the specificity of each type of praxis or context studied; the appropriateness and systematic application of analytical methods; and comparison to relevant bodies of knowledge (see Angrosino 2007 for a useful introduction to ethnographic criteria of validity). In these cases a fresh perspective and insights into new relationships are valued because the researchers are not seeking one true piece to add to a puzzle, but rather an ever-growing body of different perspectives on a subject, which in turn expand what that subject can be to us.

A constructivist position involves an epistemological ontology. More specifically, this reflects the idea that phenomena never exist independently of human, discursive engagement. They are, using Judith Butler’s term, ‘constituted’ by our continuous performance of them (Butler 1993, 1–23). While constructivist research tends to study performative manifestations and mechanisms of discursive constitution and iterative change, it always involves the dilemma that the analytical and theoretical knowledge produced is about phenomena that in part are constituted through the act of research. Much constructivist research uses theoretical concepts from specific schools of philosophy to verify arguments, critique existing norms, and reveal our performance of them. For validity it is important, however, that this work is not unaware of the constructive performance of both the theory used and the researcher’s own actions. In other words, both the phenomena studied and the act of studying become potential subjects of analysis. The outcome from constructivist research that is often valued involves revealing and critiquing norms and forms of organisation.

In the area of artistic research (or Practice as Research) ontology can be understood as emergent because the phenomena that are examined do not fully exist prior to or outside of the researcher’s engagement with them. The researcher is both bringing phenomena into the world and studying how such phenomena emerge. This work tends to involve an enactive epistemology as the researcher gains access to insight through active and embodied engagement (see Haseman 2007; Kershaw 2009; Nelson 2013; Arlander 2018 for different approaches that share this notion). A significant difference between this paradigm and constructivism is that the researcher has agency. He, she, or they are not primarily regarded as involuntary participants in the iterative performance of discourses; rather, they are aiming to bring something new into the world by, for example, developing techniques, affecting change, or rendering implicit artistic knowledge explicit. There are many different views on how to validate artistic research, but three criteria of validity that most agree on are awareness, responsiveness, and utility. The work benefits from being planned with the explicit aim of producing knowledge, and thus, awareness of the creative methods used and choices made is often prioritised. This plan is typically a starting point, as it will likely need to be revised in response to insights and possibilities as they emerge; the knowledge produced tends to feed back into the field of creative practice in useful ways.

Questions about whether the consistent methods of the sciences, the subject-specificity of most analytical scholarship, or the emergent process of artistic research takes priority are the primary and most important sites of negotiation in interdisciplinary collaborations. Such choices will determine validity and utility; they will decide what kind(s) of knowledge you are producing and who will recognise it as knowledge (see Hansen 2018 for an elaborate discussion of this question).

Imagine that you, as a dance artist, have gathered a team of research collaborators, including an experimental psychologist, an ethnographer, and a performance studies scholar. If you design a scientific experiment in a contextually controlled lab with a large, and thus statistically valid, group of participants in order to produce generalisable knowledge about the psychology of your subject, then you lose the ability to study relationships in their context-specific natural setting, which the ethnographer may prioritise. If instead you study relationships in the field, the work will not be as theoretically driven as the constructivist performance studies scholar might be interested in, nor will it involve the enactive facilitation of emergence and recording of embodied experience that can produce useful results for the artistic field. I could keep going. In their most rigorous and recognisable form, each of these discipline-specific methodologies are mutually exclusive. Regardless of whether you work collaboratively or are interested in incorporating scientific, ethno-sociological, or analytical research methods in your artistic research, something has to give, compromises must be made, and very different forms of knowledge must be related to one another.

The first step in such a process is to expand the articulation previously discussed from the clarification of terminology and explanation of procedures to exchange of methodological principles. The purpose is to ensure that all collaborators understand how different criteria of validity are informed and why some are more important than others within each discipline. The second step is to design the overall research project in such a way that that the most important criteria, which each discipline depends on for validity, are met. The third step is to negotiate the criteria that are mutually exclusive and be prepared to give, adapt, defend, and develop solutions that are truly interdisciplinary in the sense that they do not already exist within a single discipline.

The Aging Dancers project identifies interactions between a series of demands and challenges that affect the professional practice of Canadian dancers above sixty and examines the strategies these dancers have developed to meet them. I have identified factors that present demands and challenges in collaboration with dance scientist Sarah Kenny through a pilot study. We will examine these factors more fully in the future with a larger team from the disciplines of dance, kinesiology, psychology, and economics. The identified factors are: artistic, material, discursive, physical, and mental (Hansen and Kenny 2018).

The overall aim of this study is to deliver strategies for how to meet challenges and articulate values in support of dancers who wish to continue dancing far past the age of thirty-five when many leave the industry. To reach that objective it is not sufficient to examine one factor or several factors in isolation from one another, we need to look at the more complex interactions between these factors and extract insight into affective strategies. Such a take on the subject requires exchange and dialogue between methodologically different areas of knowledge.

Two of these areas are scholarly discourse analysis and scientific analysis of injury patterns and kinetic movement adaptations. Discourse analysis empowers us to examine negative discourses of the ageing body in the dance industry and their effect on the professional identity and opportunities of ageing dancers. However, the theory of the discursively constituted body that informs these analytical tools (Butler 1993) cannot be productively upheld when examining injury patterns and the kinetic adjustment and support of movement that prevent injury later in life. Rather, we need to look at biomechanical principles that regard the biological structure of the body as an objective reality. When faced with such mutually exclusive ontologies, I name them and elect to let them sit side by side. I accept that discursive values can affect the physical body and vice versa and invite my collaborators to engage with that possibility. When working on the analysis of interactions and publishing results, the team will need to continue to articulate such inherent differences and name the choices that follow as premises of the suggestions made.

It is useful to be aware of the stakes. If the knowledge produced does not adhere to criteria of validity and thus cannot be recognised as knowledge by editors/presenters, assessors of funding bodies, and the stakeholders who may apply the research results to practice, then it also becomes very difficult to disseminate and fund the work. As a result, it is unlikely to gain the intended impact.

Engaging with subject material beyond your experiential or discipline-specific reach

Working with subject material, methods, and methodologies that differ from the researcher’s own field and praxis empowers him, her, or they to engage with knowledge beyond their experiential reach. As a physically disabled dance dramaturg, I depend on this empowerment in all my work and inquiry into the aspects of dance that I can never register experientially. The work does far more than circle or represent the embodied experience I cannot have, it articulates, measures, and repurposes insights about the dancing mind and body, and about creative processes that otherwise would not be available to anyone. It makes me better at hypothesising about and considering the experience I cannot have, but it also takes me and my collaborators far beyond that in ways that help advance the field of praxis studied. The latter is a product of moving beyond the limited discipline-specific reach while maintaining some strength of discipline-specific methodology and insight.

Returning to the example of the Aging Dancers study, I can analyse social discourses of body values in dance as a scholar and I can also conduct empirical research into the material conditions performers of contemporary dance face when they transition out of the industry. I need the methodological tools and knowledge of the kinesiologist to understand the physical demands that also partake in the decision to transition and how they are met by ageing dancers who continue to dance. To consider cognitive or perceptual demands and strategies it is necessary to apply methodology from psychology. The strategies dancers develop over a lifetime to meet or counteract demands are embedded in creative approaches, which are accessible to me as a dance dramaturge through demonstrations and exchanges in the dance studio. There are factors which affect ageing dancers’ praxis that I would not be able to consider with sufficient precision if I were to inquire through one of these disciplines alone.

The blind spots and naïve assumptions that all disciplines involve are also challenged. When co-editing an interdisciplinary book on the cognition of memory in the performing arts (Hansen and Bläsing 2017), dance scientist and psychologist Bettina Bläsing and I were discussing a series of assumptions that are common within one discipline, but are highly problematic from the perspective of another. Bläsing noted that performing arts scholars sometimes used results from scientific studies of memory systems as theory in ways that far overreach the appropriate range of transfer. I observed that in some cases, dance psychologists discussed and referred to their intervention as ‘dance’ or even ‘physical action’ without factoring in the significant differences in memory demands of, for example, codified ballet movement and contemporary dance improvisation. We were able to catch such areas of naïveté and guide our authors and each other through the task of addressing them because we chose to approach our differences as products of complementary rather than competing areas of expertise.

Project designs with cross-disciplinary transfer and feedback loops

There are different models for how to collaborate across disciplines while still producing knowledge that is recognisable. The most common solution is to set up a hierarchy among disciplines with openness towards each other. Dance artists may deliver dance tasks and choreography for the experimental interventions of dance scientists or psychologists and they may also advise scientists on terminology (e.g. Vicary et al. 2017). In other cases dance artists are involved in delivering interventions or participate as research subjects in studies that involve non-hierarchical collaboration between neuro-scientists, social ethnographers, and dance studies scholars (e.g. Reason et al. 2016; Waterhouse, Watts, and Bläsing 2014). While the collaboration between scientists and scholars involves active negotiation of methodology and different forms of data collection, the dance artists are still serving the research and rarely producing knowledge or offering leadership. Although I often refer to and draw upon the results of the studies cited above, I also think that it would be interesting to revisit these studies with a central artistic research component.

In my experience, artistic research can provide much needed connective tissue between disciplines (Hansen 2017). Scientific studies typically find an effect caused by an intervention or the real-life experiences of a specialised group. They may also identify statistical correlations between different factors. It often is a much harder challenge to explain why the effect happened or how the correlation emerged. To do so it can become necessary to take a close look at mediating processes. Examining processes as they unfold is exactly what artistic researchers excel at. This orientation can, furthermore, be a precondition for the research results to be of use to artists. A verified hypothesis is rarely directly applicable to artistic practice; an understanding of which creative approaches, components, or challenges that can bring about the effect is far easier to use to develop creative strategies and methods.

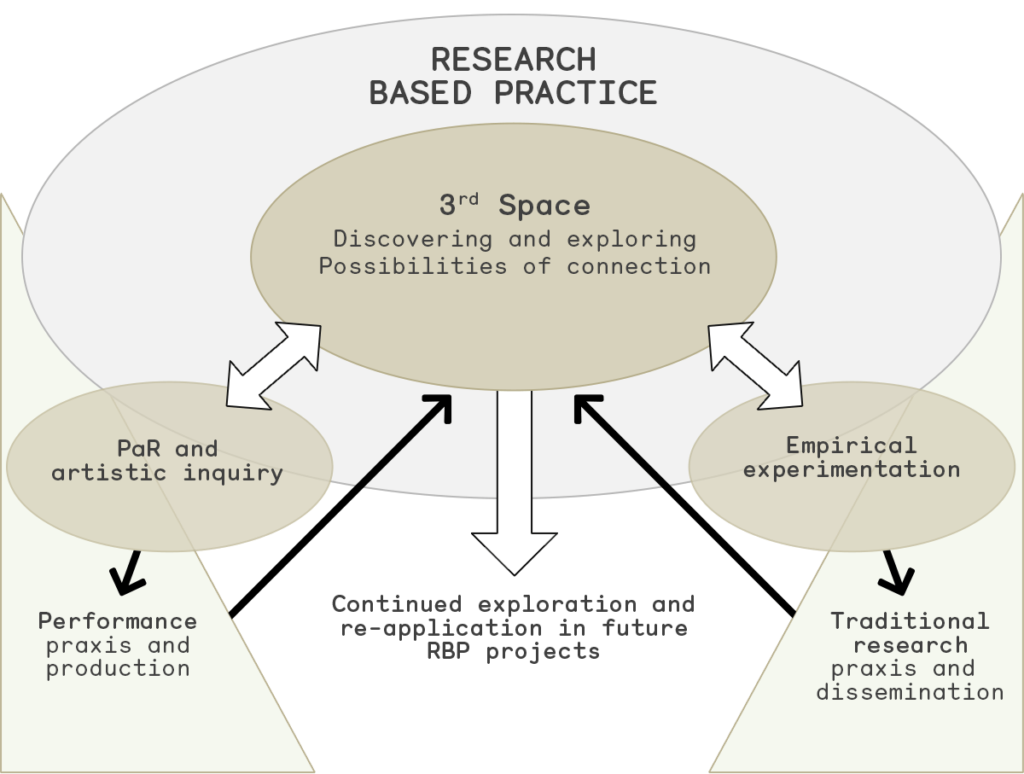

In 2009, Bruce Barton and I co-designed a research model with the intention of facilitating multidisciplinary knowledge production and interdisciplinary contamination without subordinating one discipline under another (Hansen and Barton 2009). We named the model Research-Based Practice in order to emphasise the utility for practice that artistic research brings to the model, yet we differentiate it from Practice-based Research (Practice-based Research, Practice as Research, and Performance Research are some of the many terms now recognised under the more inclusive term Artistic Research. See Barton 2018 for an overview). The model was subsequently applied to several of our respective research projects and in projects of peers and students, leading to a further developed version (Hansen 2018).

As pictured in Figure 1, this model establishes a minimum of three distinct spaces, or I could say frames, for research: two discipline-specific spaces and one 3rd space for interdisciplinary exploration. A research topic and perhaps even questions and participants are shared across the discipline-specific spaces. In these spaces, however, the research is designed to adhere to the methodological norms and criteria of validity of a leading discipline in order to ensure that the research output will have impact for the associated field. Results, questions, problems, new ideas, and even procedures from these spaces are then transferred to the shared 3rd space, in which criteria of validity are suspended in order to examine mediating processes and explore possible connections and ideas that are not suitable for examination within a single discipline. Discoveries and abductive jumps (associative inferences) made in the 3rd space are then pulled back into the discipline-specific spaces, adding significant, interdisciplinary components and perspectives to the work.

The examples that the model above was based on bring together Artistic Research (or Practice as Research) and scientific experimentation, but the model could include any two or more disciplines.

Returning to the phases of my research into the dramaturgy, notation, and psychology of performance-generating systems, artistic inquiry was a fully integrated component that often gave me and my collaborators access to mediating processes. My artistic collaborators were also actively contributing to knowledge production. Different project phases adhered more to the methodologies of one discipline than another, as illustrated in the RBP model.

The early phases surrounding House’s rehearsal process on Hay’s solo provided him with dramaturgical reflection and perspectives that were cycled into his creative research. The interview and writing forms used during these phases also extracted dramaturgical and experiential knowledge for future use.

Hypotheses about how the components of this system might generate performance were then tested empirically and analytically by completing a DST analysis of self-organising patterns and actions across four nights of performing the work.

We made use of the knowledge produced through both the artistic research and the analytical work when co-authoring teachable forms of notation and shortcuts to the generating principles of the solo (see Hansen with House 2015).

When these notations and shortcuts were brought back into the classroom, we once again chose artistic research as our framework. Students were invited to join us on a journey of trying to understand how performance generating systems work, how they generate performance and affect the performer, through embodied and reflexive engagement with practice. They went through learning curves, reflected on experiences of relevance to the joint research question in written observations, and took their knowledge back into rehearsals.

When our hypothesis about the effect on cognitive and learning capacity was tested scientifically, we adhered to experimental methodology and kept the tests isolated from the artistic research questions. However, now that a significant effect has been discovered and it has become relevant to explain it, the qualitative daily observations of the participants are key. When analysing this large amount of text using both pre-established codes and ‘grounded codes’ (that is, subject codes that emerge out of the material) we will understand which tasks and which responses to these tasks that could have caused the measured effect (see Hansen and Oxoby 2017; the results of a follow-up study from 2018 have not yet been published).

With that knowledge in hand, it will become possible for me and House to return to our notations and shortcuts and to adapt them in such a way that the cognitive capacity needed to perform in these works is trained by gradually increasing the complexity levels and giving learners the guidance and tools they need as they learn.

Documentation

When working across disciplines, it can be useful to produce more or different kinds of documentation in order to demonstrate discoveries to collaborators. At times it may also make sense to extract data sets that can be processed using methods and tools from the methodologies of the respective disciplines involved.

In the case of the Performance Generating Systems project we were, for example, producing two kinds of data and one form of output from our coursework with students:

- Standardised cognitive tests conducted before and after the course and repeated at the same interval with a control group that did not take the course. We also surveyed information about years of training, past experience with improvisation, mental health conditions, language fluency, gender, and age to help us consider variables and alternate explanations for our findings.

- Subjective daily praxis-observations written by the participants.

- Performance praxis and new performance generating systems created by the participants.

Different groups of researchers, research assistants, and participants were collecting and processing this data or producing the creative output.

On the one hand, the fact that we were able to work with the same group of participants and the same intervention increased our ability to relate the different kinds of knowledge to each other. On the other hand, each discipline had to work within the limitations that derived from other disciplines.

For example, the students were invited into an artistic research process with full openness and agency. Yet, we had to keep them blind to our hypothesis about how the performance generating systems might affect the participants’ cognition and learning. Withholding the hypothesis was important because the cognitive experiments required participants to be unbiased about the values tested. The boundaries produced by a primary criterion of validity of one methodology limited our ability to consistently apply a criterion used within another methodology.

To offer another example of these strengths and limitations, I would like to switch to the Aging Dancers project. We plan to: commission a short but physically demanding choreography; teach it to dancers above sixty; task these participants with making the choreography comfortable and interesting; analyse their choices and strategies comparatively. We will need access to the dancers’ subjective experience of the physical adaptation, mental processes, and artistic approaches they use while dancing. However, because we are also recording the performances to extract objective data for kinetic analysis and comparison, we cannot task the dancers to talk through their dancing as that will affect the movement. Instead we will work with the second-best tool and ask the dancers to annotate their video recordings shortly after the recording. Memory recall triggered by video is different from live notation of experience and our analysis of results will need to account for this difference.

A dance scientist would prefer to isolate the physical adaptation of movement from creative and mental strategies in order to arrive at cleaner data with fewer competing causes of the kinetic changes recorded. However, such isolation would separate physical and mental aspects that are closely integrated in the creative strategies that our subjective data collection is designed to record. This means that everyone needs to compromise. However, the fact that the kinetic analysis and the analysis of subjective artistic experiences are based on the very same performance, instead of separate experiments, makes the two forms of knowledge far easier to relate in our discussions, since they concern the exact same choreographic challenge and performance situation.

The examples offered above demonstrate that when multiple types of data are extracted and processed differently with the aim of producing and relating different kinds of knowledge, the research team ends up with a puzzle of competing criteria of validity. Solving this puzzle can require all parties to prioritise the criteria and agree to compromise around the lower priorities.

Utilising the many routes inquiry can take across multiple projects

A project of the scope of the examples offered here is resource demanding. If working with smaller amounts of funding or limited access to resources, it can be useful to involve collaborators early and have an open conversation about their interests and ability to contribute resources such as space, production resources, research assistance, test materials, data processing software, time, and funds to pay participation fees. Make use of opportunities that save resources.

When planning the Performance Generating Systems project, I pitched teaching an advanced dance improvisation class at the University of Calgary, framed the class as artistic research, and used it as the intervention and case for my collaborators. A teacher–student relationship does present ethical complications and will require a thorough ethics protocol, as it is important that students feel entirely free to opt in or out of the study while taking the classes. However, this setup made recruitment of participants less time-demanding because we were recruiting from a group that had already expressed interest in the subject matter. Participation fees were also reduced in this setting as the participants were paid only for their test and interview contribution and not for workshop participation. It also gave us access to space free of charge and two researchers were paid by the educational institution for delivery of the intervention workshops as class or guest instructors.

It can also be useful to tailor the scope of the project to the resources available. The researcher may start with a small pilot study or with fewer participants and collaborators. He, she, or they may decide to offer the workshop series twice to refine and add new forms of observation and data collection gradually. Results from a pilot or early phase can then be used to motivate grant applications and generate interest and resource sharing from new collaborators.

In addition to accessing resources and establishing buy-in from collaborators, there are other benefits from completing a larger project in phases or even connecting several projects. The work gets to mature, dance tasks and approaches can be advanced, problems can be solved, test measures can be adjusted, and results can be applied to different contexts.

Articulation of knowledge and impact

When an interdisciplinary project is designed to allow for multiple kinds of knowledge to be produced, as I have advocated for here, these outcomes can be disseminated and applied to a larger number of fields than a discipline-specific project, effectively increasing the reach and impact of the research. I have led projects with outputs published in interdisciplinary journals, psychology journals, dance journals, performance studies journals, and essay collections covering a comparable range of readers from different areas. The same projects have also outputted touring and award-winning dance works, course designs, and workshop contents. They have produced tools for the notation or dramaturgical composition of improvisation systems and devised work. Finally, new research models and test tools have been developed, published, and used in subsequent projects.

The majority of the publications are co-authored, though I initiated the writing and served as the primary author. University institutions do, as a rule, value co-authored publications lower than single-authored publications when assessing the output of artist-scholars in the arts and humanities. In some contexts, output of artistic research that is shared in public performances, workshops, or on open-access websites is also valued below peer reviewed articles. Depending on the institutional norms of the researcher’s context, it may be advisable to write an occasional single-authored article or chapter in order to live up to expectations and counter this institutional disadvantage. Such writing does becomes easier when reference can be made to a diverse body of other kinds of output. The institutional expectations mentioned here are changing in many contexts and new measures of impact that incorporate community involvement, performance output, and collaborative efforts are being developed. Funding agencies expect such results, and thus, institutions will also have to adjust over time. Our work helps bring about this institutional change and it makes us uniquely positioned to benefit from it.

The primary reward of inter- and multidisciplinary dissemination, as I see it, is that the fields we are bringing into dialogue in our research can access and draw on our results for future research and application to praxis, effectively continuing the dialogue.

References

Angrosino, Michael. 2007. “Focus on Observation” and “Analysing Ethnographic Data.” In Doing Ethnographic and Observational Research edited by Uwe Flic, 53–76. London: SAGE.

Arlander, Annette. 2018. “Agential cuts and performance as research.” In Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact, edited by Annette Arlander, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz, 134–51. New York: Routledge.

Barton, Bruce. 2018. “Introduction I. Wherefore PAR? Discussion on ‘a line of flight’.” In Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact, edited by Annette Arlander, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz, 1–19. New York: Routledge.

Bernard, H. Russell. 2013. “Research Design: Experiments and Experimental Thinking.” In Social Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. 2nd edition, 90–110. London: Sage.

Butler, Judith. 1993. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York: Routledge.

Callaway, Ewen. 2013. “Leap of thought: Ewen Callaway meets cognitive scientist David Kirsh, who works with choreographer Wayne McGregor.” Nature 502, no. 7470, 168.

deLahunta, Scott, Gill Clarke, and Philip Barnard. 2012. “A conversation about Choreographic Thinking Tools.” Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices 3, no. 1–2, 243–59.

Hacking, Ian. 1999. “The Rationality of Science After Kuhn.” In Scientific Inquiry: Readings in the Philosophy of Science, edited by Robert Klee, 216–27. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hansen, Pil. 2015. “The Dramaturgy of Performance Generating Systems.” In Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement, edited by Pil Hansen and Darcey Callison, 124–42. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hansen, Pil. 2017. “Connective Tissue: Practice as Research in Cross-disciplinary Research Collaborations.” Canadian Theatre Review on Articulating Artistic Research 172 (Fall): 18–22.

Hansen, Pil. 2018. “Research-Based Practice: Facilitating Transfer Across Artistic, Scholarly, and Scientific Inquiries.” In Performance as Research: Knowledge, Methods, Impact, edited by Annette Arlander, Bruce Barton, Melanie Dreyer-Lude, and Ben Spatz, 32–49. New York: Routledge.

Hansen, Pil, and Bruce Barton. 2009. “Research-Based Practice: Situating Vertical City between Artistic Development and Applied Cognitive Science.” TDR: The Drama Review 53, no. 4: 120–36.

Hansen, Pil with Christopher House. 2015. “Scoring the generating principles of performance systems.” Performance Research 20, (6): 65–73. doi:full/10.1080/13528165.2015.1111054.

Hansen, Pil, and Bettina Bläsing. 2017. “Introduction: Studying the Cognition of Memory in the Performing Arts.” In Performing the Remembered Present: The Cognition of Memory in Dance, Theatre and Music, edited by Pil Hansen and Bettina Blaesing, 1–25. London: Bloomsbury Methuen.

Hansen, Pil, and Robert J. Oxoby. 2017. “An Earned Presence: Studying the effect of multi-task improvisation systems on cognitive and learning capacity.” Connection Science 29,(1): 77–93. doi:full/10.1080/09540091.2016.1277692.

Hansen, Pil, and Sarah J. Kenny. 2018. “Physical and Mental Demands Experienced by Aging Dancers: Strategies and Values.” Performance Research 23, (7). In peer review.

Hansen, Pil, Karen Kaeja, and Ame Henderson. 2014. “Transference and transition in systems of dance generation.” Performance Research 19, (5): 23–33. doi:abs/10.1080/13528165.2014.958350.

Haseman, Brad. 2007. “Rupture and Recognition: Identifying the Performative Research Paradigm.” In Practice-as-Research: Approaches to Creative Arts Enquiry, edited by Estelle Barrett, and Barbara Bolt, 27–34. London: I.B. Taurus.

Kershaw, Baz. 2009. “Practice-as-Research: an Introduction.” In Practice-as-Research: in performance and screen, edited by Ludivine Allegue, Simon Jones, Baz Kershaw, and Angela Piccini, 1–17. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kirsh, David. 2011. “How Marking in Dance Constitutes Thinking with the Body.” Versus: Quaderni Di Studi Semiotici Vol. 113–115, 179–210.

May, Jon, Beatriz Calvo-Merino, Scott deLahunta, Wayne McGregor, Rhodri Cusack, Adrian M. Owen, Michele Veldsman, Cristina Ramponi, and Philip Barnard. 2011. “Points in mental space: an interdisciplinary study of imagery in movement creation.” Dance Research 29, (2): 402–30.

Nelson, Robin. 2013. Practice as Research in the Arts: Principles, Protocols, Pedagogies, Resistances. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Popper, Karl. 1999. “Falsificationism.” In Scientific Inquiry: Readings in the Philosophy of Science, edited by Robert Klee, 65–71. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reason, Matthew, Corinne Jola, Rosie Kay, Dee Reynolds, Jukka-Pekka Kauppi, Marie-Helene Grobras, Jussi Tohka, and Frank E. Pollick. 2016. “Spectators’ Aesthetic Experience of Sound and Movement in Dance Performance: A Transdisciplinary Investigation.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 10,(1): 42–55.

Vicary, Staci, Matthias Sperling, Jorina von Zimmermann, Daniel C. Richardson, and Guido Orgs. 2017. “Joint Action Aesthetics.” PLOS One 12, no. 7: E0180101.

Waterhouse, Elizabeth, Riley Watts, and Bettina Bläsing. 2014. “Doing Duo – a case study of entrainment in William Forsythe’s Choreography ‘Duo’.” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8, 812. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00812.

Pil Hansen

Dr. Pil Hansen is an Associate Professor at the School of Creative and Performing Arts, University of Calgary (Canada), a founding member of Vertical City Performance, and a dance/devising dramaturg. Her empirical and Practice-as-Research experiments examine the effect on memory, perception, and cognitive flexibility of creative processes. Hansen developed the tool-set “Perceptual Dramaturgy” and, with Bruce Barton, the interdisciplinary research model “Research-Based Practice.” Her scholarly research is published in TDR: The Drama Review, Performance Research, Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, Connection Science, Theatre Topics, Canadian Theatre Review, Peripiti, Koreografisk Journal, MAPA D2, and thirteen essay collections. Hansen is primary editor of Dance Dramaturgy: Modes of Agency, Awareness and Engagement (2015) and Performing the Remembered Present: The Cognition of Memory in Dance, Theatre and Music (2017). She has also dramaturged 27 artistic works, many of which have won awards and toured nationally and internationally.