Abstract

Art and culture for well-being is a growing trend in Finland and internationally. A variety of challenges such as the discontentment of children and young people, the aging of the population, the growing needs of immigrant groups and the integration of various population groups require pro-active and preventive measures. Answers to these challenges are increasingly sought from arts-based approaches. Likewise, arts are called for help as the success of organisations in post-industrial countries is increasingly based on human resources. How do performing arts provide guidance, assuagement and remedy outside their own traditional boundaries? For example, applied theatre and community dance provide means for artistic interventions to address organisations’ needs for innovation, learning, communication, solidarity, well-being and so on. Artistic interventions can be defined as artist-led initiatives that help organisations through the arts to develop their activities or competencies. In my paper, I discuss, how, or under which conditions, could artistic interventions in performing arts be regarded as artistic research. How could artistic research be embedded in artistic interventions as a form of inquiry? In addition, I will briefly contemplate the potential of artistic interventions as performative and transformational practice by examining how artistic interventions could make impact and instigate change in organisations. Finally, I consider how artistic interventions as artistic research could be studied from inside the practice.

Introduction

My understanding of artistic interventions comes from six years of leading a specialist team in performing arts that provides theatre- and movement-based services for organisations.(1)The Development Team (formerly the Unit of Continuing Education and Development) at the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki includes Irma Koistinen, Pekka Korhonen, Satu-Mari Korhonen and Riitta Pasanen-Willberg. The team has been involved in several projects on arts-based work at national and European levels.(2)The projects include Transmission (2002–2006), Taika (2008–2011), Taika II (2011–2013), Kolmas lähde (2008–2010), Quality of Life: Creative pathways of family learning (2010–2012), Training Artists for Innovation (2011–2013) and Creative Clash Network (2013–). This paper is based on research and development that has been undertaken during the past few years in two European projects – Training Artists for Innovation (TAFI) and its sister project Creative Clash – that focus on artistic interventions in organisations.(3)As the two projects are coming to a closure in the spring of 2013, a new platform – Creative Clash Network – will be set up to enhance training, research and development of artistic interventions in Europe. TILLT/Skådebana Västra Götaland in Sweden as one of the founding members of the platform coordinates the initiative. Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki is one of the founding members together with Artlab (Denmark), Cultuur-Ondernemen (The Netherlands), KEA European Affairs (Belgium), WZB (Germany), C2+i (Spain) and 3CA (France). In the two projects, our work has been motivated by the fact that in Europe, there is a growing market for artistic interventions: that is, artist-led approaches that help organisations develop their work processes, competencies and innovations.

In this paper, my aim is to probe under which conditions, can artistic interventions be regarded as artistic research. Can artistic research be embedded in artistic interventions as a form of enquiry? I will also propose some ideas on how to study artistic interventions as artistic research from inside the practice. In addition, I will briefly address the potential of artistic interventions as performative and transformative practice.

What are artistic interventions in organisations?

Artistic interventions constitute an emerging domain in the arts, where art and organisations meet to create value to organisations. Yet, that is not what someone would call “industrial arts” but a new form of artistic practices.(4)Currently, there is no consensus of opinion among different stakeholders on the art status of artistic interventions in organisations (i.e. art or applied art). Yet, looking at the diversity of approaches, I would tentatively propose some kind of a continuum where ‘art for arts sake’ is at one end of the continuum and strict instrumentalisation of artistic methods without artistic ambitions is at the other end. In most cases, artistic interventions in organisations are not about simple instrumentalisation of the artist’s methods for non-artistic purposes. Rather, they involve high ambitions and complex artistic processes that often give rise to works of art that are displayed or performed in public. To a certain degree, one could say that artistic interventions link to art interventions in conceptual art. That is, art enters into a non-artistic context in an attempt to instigate change.(5)As Wikipedia informs us, “intervention art may attempt to change economic or political situations, or may attempt to make people aware of a condition that they previously had no knowledge of” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_intervention (accessed 5.1.2013)

While the intervention as a concept may link to the idea of subversion, nowadays artistic interventions in organisations are almost always exercised in agreement with those who are the target of the intervention.

Artistic interventions in organisations can be defined as commissioned artistic processes, which are led by professional artists and take place in organisational settings. They involve processes of artistic inquiry, art making, co-creation and co-reflection with the participants from the client organisation; for example, executive teams, employees, team members, customers, local residents, etc. The outcomes of such processes provide opportunities for the participants and the client organisation to perceive its issues and topics from fresh perspectives – to see things differently. In a sense, artistic interventions operate as a creative means to distance organisational issues at hand so that they can be grasped, reflected upon and improved.

Why now?

Economists and organisational theorists claim that the business landscape has changed drastically in post-industrial countries during the early twenty first century. (See for example: Pine and Gilmore 1999, Rifkin 2000, Davis 2009, Kotler and Caslione 2009, Berthoin Antal 2011, Schiuma 2011, Böhme 2012) It has become less predictive, more people-dependent, increasingly multicultural, interdisciplinary, aesthetic and experience-driven. As Sir George Cox puts it in his review of creativity in business, organisations need to “draw on the talents of a flourishing creative community” (Cox 2005, 10). Such landscape opens up opportunities for the arts as they are seen to have an important role in organisations, which are increasingly dependent on employee’s creativity, imagination, intuition, aesthetics and emotions (Schiuma 2011).

Recently, a number of organisations have started to look for answers from the arts as the following testimonies show:

We business people need to get into a completely different way of looking at things. We must meet other competencies and a new (creative) logic that challenges our way of thinking. Otherwise, we get stuck. Artist-driven enterprise development gives us new tools to think outside the box, which gives much, much more than ordinary methods. (Bertil Lindström, the owner of Citymöbler and Brittgården Fastigheter (Sweden) as quoted in Heinsius and Lehikoinen 2013, 7.)

Innovating through artistic interventions with our organisation has been a clear success, which is why we need artists with the ability to understand the business world, its logic and languages. We need artists who are guided by exploration and research in their work, who are able to interact in unfamiliar environments, who can propose and trigger divergent thinking; artists who in fact like people. Artists, who, like us, are convinced that they can transform organisations and societies based on creativity, collaboration between different players and risk-taking. (Urtzi Zubiate Gorosabel, the R&D+i Director of Fagor Group (Spain) as quoted in Heinsius and Lehikoinen 2013, 9.)

Also Finland has been quick to react to the European Commission’s observation that cultural and creative fields are a poorly harvested resource when it comes to achieving the objectives of the EU’s growth strategy. (Kirsi Kaunisharju and Merja Niemi, in the Foreword of Heinsius and Lehikoinen 2013, 6.) The value of arts-based creativity and cultural understanding for organisations has been acknowledged now in a number of national policy documents and processes.(6) See the report on the futures of cultural professionals, modern life and work by the Committee for the Future in the Parliament of Finland (Hautamäki & Oksanen 2011), the national working life development strategy by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy (2012), the Creative Economy at Work -project by the Ministry of Education and Culture (Niemi 2012), the Valuable Working Life -process by the Ministry of Education and Culture (http://www.luovasuomi.fi/soveltavataide/arvokastyoelama), and the national strategy on social and health politics by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (2010).

Artistic interventions where?

Based on cases in Denmark, Spain and Sweden, it could be argued that artists who work in artistic interventions get to meet people with various backgrounds. (See cases: Hempel 2010, www.tillt.se/kunduppdrag/ericsson-ab/ and conexionesimprobables.es/pagina.php?m1=185&id_p=331) In addition, they get introduced to a range of organizational cultures. Organisations where artistic interventions have been introduced vary including fields such as education, healthcare and medical industry, social work, information technology, product development, regional development, service development, urban planning and public transportation, just to name a few. Physically, processes in artistic interventions are carried out in heterogeneous locations some of which are artistically typical environments such as rehearsal studios or galleries and others that are more atypical sites such as meeting rooms, auditoriums, factories, hospital corridors and so on.

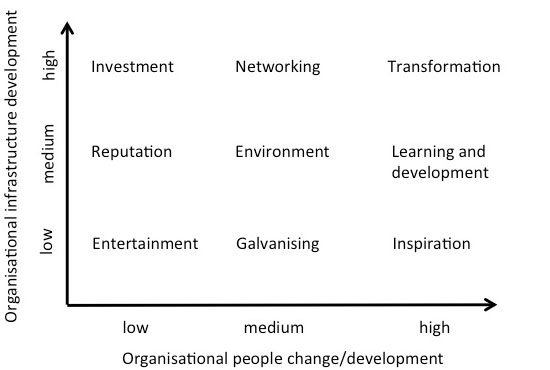

As Giovanni Schiuma’s (2011) “arts value matrix” shows (see illustration 1), artistic interventions with different focuses have different impacts on people and on the organisation’s infrastructure. In Schiuma’s matrix, the ultimate goal is to plant the seeds of artistic thinking into the very DNA of the organisation. (See the case study of Spinach in Schiuma 2011, 214–224)

Illustration 1: Arts value matrix (Schiuma 2011, 100)

On performativity and transformativity of artistic interventions

Artistic interventions can be seen as performative in a sense that they do not report or describe phenomena in the organisational reality as such. Rather, they frame it, play with it, question it and disrupt it in an attempt to open up a dialogical space where new interpretations and new identities can be constructed by the participants. The fact that such co-creation and co-reflection are not limited to speech and writing but can include a full range of human expression such as dancing, filming, painting, performing, playing, sculpting and so on is all important because, to quote Kenneth Gergen:

In doing so there is a vital expansion in the range of those who can be reached … The charge of elitism is also softened … [and] many of these expressive forms invite a fuller form of audience participation. (Gergen 1999, 188.)

Thus, compared to more traditional modes of consulting, it could be suggested that artistic interventions provide the participants significantly richer opportunities to address and reflect upon various organisational phenomena experientially. Further, multimodality in artistic interventions makes it easier for the participants as adult learners to acquire, process and share information in ways that better correspond with multiple intelligences (for multiple intelligences, see Gardner 1983, Gardner 1993 and Gardner 2000) as well as individual learning styles (for different learning styles, see, for example, Kolb 1984, Honey and Mumford 1992, Cottrell 1999, Hawk and Shah 2007, Leite et al. 2009) and different styles of communication.

Artistic interventions can be understood as artist-led social innovations in a sense that they often aim for some form of social change in organisations.(7)Murray, Caulier-Grice & Mulgan define social innovation “as new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs and create new social relationships or collaborations. In other words, they are innovations that are both good for society and enhance society’s capacity to act” (Murray et al. 2010, 3). For a concise overview of the concept’s theoretical development, see Chapter 4 in Empowering people, driving change: Social innovation in the European Union by Bureau of European Policy Advisers (2011). Many scholars have addressed the transformative potential of artistic interventions (see, for example, Berthoin Antal 2011, Rantala 2011, Schiuma 2011, Korhonen 2012, Pässilä 2013) but now there is also research-based evidence available on the impact of artistic interventions.(8)In a recent literary review, Ariane Berthoin Antal and Anke Strauß (2013) identified 29 categories of impacts of artistic interventions including for example ‘dealing with the unexpectedness’, ‘questioning routines’, ‘work climate’ and ‘organisational culture’. They organised these categories into eight groups as follows: ‘strategic and operational impacts’, ‘organisational development’, ‘relationships’, ‘personal development’, ‘collaborative ways of working’, ‘artful ways of working’, seeing more and differently’, and ‘activation’ (Berthoin Antal and Strauß 2013, 15.) At the end of the day, how artistic interventions succeed in transforming ways of thinking, work processes, products and services depend on how open the leaders and employees in the client organisation are to the intervention process. It is necessary for the leaders of organisations to understand that it is their job to ensure the successful implementation of new and creative approaches in the everyday of the organisation. In addition, it could be suggested that the success of interventions depends also on the duration of the intervention, the clarity of its aims, appropriate methodology as well as the competencies, the experience and the personal characters of the artist/s involved. As existing degree programmes in the arts do not tend to provide the special skills and competencies that artists need in artistic interventions, professional development and training is needed.(Vondracek 2013.)

What competencies artists need in artistic interventions?

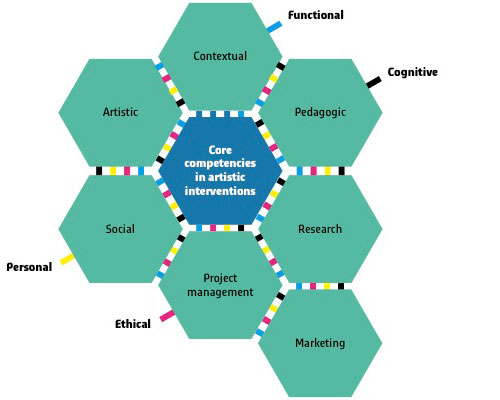

Illustration 2: Strands of Competency and Core Competence Areas in Artistic Interventions (Lehikoinen 2013a, 51.).

Devising and carrying out artistic processes that engender change in organisations call for a broad knowledge base and special skills. In the Training artists for innovation -project, our project team identified core competence areas that artists need as they work with organisations in artistic interventions (see illustration 2).(9) The TAFI project team included Roberto Gómez de la Iglesia (Spain), Anna Grzalec (TILLT, Sweden), Joost Heinsius (Cultuur-Ondernemen, The Netherlands), Gerda Hempel (Artlab, Denmark), Kai Lehikoinen (University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland), Arantxa Mendiharat (Conexiones improbables, Spain), Anna Vondracek (KEA, Belgium). Also Ariane Berthoin Antal (WZB, Germany) made a valuable contribution to the development of the competence framework. In the framework, research is included as one of the core competence areas next to other areas such as artistic/creative, contextual, social, pedagogic, project management and marketing. As I have articulated these competence areas in detail elsewhere (Lehikoinen 2013a, 49–63.), I now shift my focus to the relationships between artistic interventions and research.

Is it research?

In the line of Schiuma’s (2011) arts value matrix, an organisation can invite a stand-up comedian to enlighten a seminar or bring in a dancer to run a workshop on contact improvisation to enhance its team-building process. A stand-up comedian can poke blind spots and make people see their world from unexpected perspectives but it is hardly research. Likewise, a dancer can help a group of people gain trust and rapport through contact improvisation exercises but that is not research either. These artistic intervention practices serve their purpose as long as they are devised and carried out professionally. However, I would argue that they are not research because they lack the consciously articulated research orientation, the research process, the publication of research results, and the peer-review.

This is not to say that artistic interventions can never be research. Ariane Berthoin Antal’s (2011) comparative study of artistic interventions in Europe describes AIRIS, which is a uniquely tailored 10-month process that the Swedish producer TILLT has offered to more than 70 clients since 2002. AIRIS contains a two-month research period in the organisation before the intervention process begins. Disonancias, a Spanish programme that has delivered numerous nine-month artistic interventions between 2005 and 2009 in the Basque Country, is another example of research-based artistic interventions that Berthoin Antal mentions. Disonancias “is based on the premise that artists are researchers by definition” (Berthoin Antal 2011, 43.) while “co-research” and “open collaborative innovation” constitute some of the key processes of the Disonancias programme. (Berthoin Antal 2011, 43.)

Based on the case descriptions in programmes like AIRIS and Disonancias, it could be argued that artworks and performances that emerge from the critically reflective and collaborative artistic inquiry processes in artistic interventions yield fresh insights and new understandings.(10)For case studies, see Kirsi Kaunisharju and Merja Niemi, in the Foreword of Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) 2013, p. 6. The intervention process and its outcomes are documented, reported and shared in public events to relevant stakeholders for critical review both in AIRIS and in Disonancias. (Berthoin Antal 2011.) In other words, an extended peer-review takes place in seminars where artistic interventions are presented. Based on the above, it could be claimed that both AIRIS and Disconancias entail components of research. To emphasise that, I prefer to call artistic interventions that embody research components that produce materials for critical reflection as research-based artistic interventions. But, are they artistic research?

Is it artistic research?

Henk Borgdorff defines artistic research as “cutting-edge developments in the discipline that we may broadly refer to as ‘art’”. (Borgdorff 2009, 20.) He elaborates on the definition as follows:

It is about the development of talent and expertise in that area. It is about articulating knowledge and understandings as embodied in artworks and creative processes. It is about searching, exploring and mobilising – sometimes drifting, sometimes driven – in the artistic domain. It is about creating new images, narratives, sound worlds, experiences. It is about broadening and shifting our perspectives, our horizons. It is about constituting and accessing uncharted territories. It is about organised curiosity, about reflexivity and engagement. It is about connecting knowledge, morality, beauty and everyday life in making and playing, creating and performing. It is about ‘disposing the spirit to Ideas’ through artistic practices and products. (Borgdorff 2009, 21, my emphasis.)

In Borgdorf’s account, I have emphasised by underlining everything that can be readily identified in much of the debate on artistic interventions that has taken place in both TAFI and Creative Clash. (See, for example, Hempel and Rysgaard 2013 and Berthoin Antal 2011.) For example, Gerda Hempel and Lisbeth Rysgaard, both from Artlab of the Danish Musicians’ Union, note that,

[s]ome of the most adventurous and experienced artists keep on developing new forms of interactions, new methodologies and new theoretical frameworks to investigate, explain or test why some approaches work and in what ways. This could be regarded as artistic research on artistic interventions. These kinds of more open experiments and often unwritten theoretical frameworks in the artistic research are central for the development of artistic innovations. (Hempel and Rysgaard 2013, 45)

Thus, it could be argued that artistic interventions as a practice can – and perhaps also should – include artistic research for at least two reasons: First, it can be used as an approach to investigate and to interpret complex organisational phenomena creatively, collaboratively and reflectively in order to instigate change; second, it can be used as an approach to study artistic interventions from inside the practice almost as a form of artistic action research.

How to go about it?

To undertake an artistic intervention, the artist-researcher does not have research questions clearly articulated from the outset of the intervention process. S/he may have a broad idea about the topic of the intervention, which derives from the needs of the client organization. However, organizations are often quite unable to pin down the exact issues that link to their needs. Therefore, as Berthoin Antal describes in reference to the AIRIS concept of TILLT, the artist-researcher needs to get to know the site of the intervention first before s/he is able to draw boundaries for the artistic intervention. The artist-researcher can articulate appropriate research questions in relation to the intervention only after s/he has:

- become acquainted with the site of the intervention;

- discussed with the different stakeholders that participate in the intervention process;

- gained some information about the key issues that are at stake in reference to the topic or the focus of the intervention. (Berthoin Antal 2011)

Following that, the artist sets up an intervention methodology, a set of artistic tasks, to observe, to collect or otherwise to produce materials that are relevant to the topic of the intervention. Here, materials need to be understood in the broadest sense as any form of documentation including artistic artefacts, performances, photographs, drawings, video recordings, transcribed focus groups or interviews and so on. How such materials are created or collected depends a great deal on the topic and the focus of the intervention.(11)In addition to artistic research, relevant research paradigms for research-based artistic interventions can be borrowed from phenomenological-hermaneutic, narrative, collaborative, critical, ethnographic, autoetnographic and intertextual approaches, for example. As in any research, also in research-based artistic interventions research questions should point to the appropriate mix of methods, never the other way around.

Often, the materials are produced collectively through artistic tasks or exercises that the artist devises for the participants of the intervention to carry out. It could be proposed that such tasks have to be devised in ways that help the participants collaboratively reflect the issue at hand (co-reflection), ventilate different perspectives and spawn creative ideas in order to come up with new or improved ideas that can be implemented into practice (co-creation). Also, it could be proposed that the artist-researcher needs to be a keen observer in order to identify what are the topics and issues that the organisation and its employees need to explore in an artistic intervention. S/he needs not only to know how to observe but also to document in action complex intervention processes and everything that emerges from such processes.

In addition, the artist needs to know how to handle, analyse and interpret multiple forms of research materials (data), which of course calls for analytical and critically reflective skills. As I have noted elsewhere, reflectivity refers to the artist’s capability to scrutinise his/her prevailing beliefs and to weigh his/her activities in order to gain new understanding about ideas under scrutiny. (Lehikoinen 2013b, 76.)

Following Kupias, reflectivity in artistic interventions can also be seen as a means to question the validity of one’s actions, interpretations and judgments. (Kupias 2001, 24.) In artistic intervention, reflections are often undertaken as a collaborative process that feeds organisational learning. (Sahlberg and Leppilampi 1994.) Thus, in artistic interventions, the artist-researcher needs not only research skills but also pedagogic skills to devise tasks of artistic inquiry, to facilitate and to encourage co-creation and collaborative reflection of the research materials.

A few words on ethics

Finally, I wish to articulate some preliminary considerations on research ethics in reference to artistic interventions.(12)Here, my musings are extremely preliminary and partial. I am acutely aware of the fact that ethics in artistic interventions is a complex topic that deserves a conference on its own. First, the artist-researcher needs to keep in mind that artistic interventions are not about the artist but about the client organisation and its needs. Successful devising of artistic interventions often requires detailed information about the client organisation. The artist-researcher needs to ensure that s/he does not disclose any confidential information about the client organisation to third parties.

The second point to consider is confidentiality. Experiential accounts are often all-important for artistic interventions, as they tend to yield useful insights for new and improved innovations. Therefore, practitioners in artistic interventions strive to give voice to participants and encourage them to share their experiences. Yet, confidentiality is often a prerequisite for people to disclose their personal experiences. Confidentiality is particularly important when artistic interventions address sensitive topics such as problems in leadership or interpersonal tensions. In such cases, the anonymity of the participants as informers needs to be secured. The challenge is, how to devise artistic tasks in ways that give space for individual voices but leave persons behind different accounts unharmed.

Last but not least, the artist-researcher may need to apply artistic devices such as magnification, parody, juxtaposition, displacement, pastiche, free association, etc., to inquire topics and issues in a radical way, highlight something that has gone unnoticed or deconstruct fixed meanings or unquestioned ‘truths’. Yet, all that emerges from such a process needs to be reflected upon and discussed considerately and in an unbiased way with the participants of the process. In other words, the artist needs to find a balance between his/her two roles: The radical artist as a challenger of ideas and the disinterested researcher as a facilitator of discussion.

Conclusions

In this paper, I have entertained the idea of artistic research in artistic interventions. I have noted that heterogeneity and diversity, which are some of the key qualities of artistic interventions, stem from the diversity of setups and approaches as well as from the unique boundaries of each intervention process that are devised to meet the needs of the client organization.

Not every form of artistic intervention entails research. However, artistic research can be incorporated into artistic interventions as long as the artist-researcher understands its research paradigm and methodologies. I have argued that artistic research can provide for artistic interventions a means to generate research materials, to analyse and interpret such materials, and also to present the ‘findings’ of such a co-creative and critically reflective process, which may or may not lead to some transformations in the client organisation. I have also argued that artistic research can provide means to study artistic interventions as a practice. In addition, I have pointed out that artistic interventions entail a complex ethical dimension that requires further discussion.

While researchers have focused on the impact of artistic interventions, it could be suspected that there are also artistic interventions that fail to achieve their objectives. Such cases deserve to be studied too, for they might yield significant insights on how to improve artistic interventions as arts-based service practice and also as artistic research.

Bio

Kai Lehikoinen is a university lecturer in performing arts in the Performing Arts Research Centre at the University of the Arts Helsinki. He has degrees in dance pedagogy and dance studies and a Ph.D. (Surrey) on dance and masculinities. His research interests include artistic interventions in non-artistic environments. He has recently published a curriculum framework for trainer training in arts-based work with people with dementia and a research policy proposal on arts-based work. Currently, Lehikoinen is writing articles on artistic interventions for a book Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts, which he co-edits with Joost Heinsius.

Notes

1) The Development Team (formerly the Unit of Continuing Education and Development) at the Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki includes Irma Koistinen, Pekka Korhonen, Satu-Mari Korhonen and Riitta Pasanen-Willberg.

2) The projects include Transmission (2002–2006), Taika (2008–2011), Taika II (2011–2013), Kolmas lähde (2008–2010), Quality of Life: Creative pathways of family learning (2010–2012), Training Artists for Innovation (2011–2013) and Creative Clash Network (2013–).

3) As the two projects are coming to a closure in the spring of 2013, a new platform – Creative Clash Network – will be set up to enhance training, research and development of artistic interventions in Europe. TILLT/Skådebana Västra Götaland in Sweden as one of the founding members of the platform coordinates the initiative. Theatre Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki is one of the founding members together with Artlab (Denmark), Cultuur-Ondernemen (The Netherlands), KEA European Affairs (Belgium), WZB (Germany), C2+i (Spain) and 3CA (France).

4) Currently, there is no consensus of opinion among different stakeholders on the art status of artistic interventions in organisations (i.e. art or applied art). Yet, looking at the diversity of approaches, I would tentatively propose some kind of a continuum where ‘art for arts sake’ is at one end of the continuum and strict instrumentalisation of artistic methods without artistic ambitions is at the other end. In most cases, artistic interventions in organisations are not about simple instrumentalisation of the artist’s methods for non-artistic purposes. Rather, they involve high ambitions and complex artistic processes that often give rise to works of art that are displayed or performed in public.

5) As Wikipedia informs us, “intervention art may attempt to change economic or political situations, or may attempt to make people aware of a condition that they previously had no knowledge of” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_intervention (accessed 5.1.2013).

6) See the report on the futures of cultural professionals, modern life and work by the Committee for the Future in the Parliament of Finland (Hautamäki and Oksanen 2011), the national working life development strategy by the Ministry of Employment and the Economy (2012), the Creative Economy at Work -project by the Ministry of Education and Culture (Niemi 2012), the Valuable Working Life -process by the Ministry of Education and Culture (www.luovasuomi.fi/soveltavataide/arvokastyoelama), and the national strategy on social and health politics by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (2010).

7) Murray, Caulier-Grice & Mulgan define social innovation “as new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs and create new social relationships or collaborations. In other words, they are innovations that are both good for society and enhance society’s capacity to act” (Murray et al. 2010, 3). For a concise overview of the concept’s theoretical development, see Chapter 4 in Empowering people, driving change: Social innovation in the European Union by Bureau of European Policy Advisers (2011).

8) In a recent literary review, Ariane Berthoin Antal and Anke Strauß (2013) identified 29 categories of impacts of artistic interventions including for example ‘dealing with the unexpectedness’, ‘questioning routines’, ‘work climate’ and ‘organisational culture’. They organised these categories into eight groups as follows: ‘strategic and operational impacts’, ‘organisational development’, ‘relationships’, ‘personal development’, ‘collaborative ways of working’, ‘artful ways of working’, seeing more and differently’, and ‘activation’ (Berthoin Antal and Strauß 2013, 15.)

9) The TAFI project team included Roberto Gómez de la Iglesia (Spain), Anna Grzalec (TILLT, Sweden), Joost Heinsius (Cultuur-Ondernemen, The Netherlands), Gerda Hempel (Artlab, Denmark), Kai Lehikoinen (University of the Arts Helsinki, Finland), Arantxa Mendiharat (Conexiones improbables, Spain), Anna Vondracek (KEA, Belgium). Also Ariane Berthoin Antal (WZB, Germany) made a valuable contribution to the development of the competence framework.

10) For case studies, see Kirsi Kaunisharju and Merja Niemi, in the Foreword of Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) 2013, 6.

11) In addition to artistic research, relevant research paradigms for research-based artistic interventions can be borrowed from phenomenological-hermaneutic, narrative, collaborative, critical, ethnographic, autoetnographic and intertextual approaches, for example. As in any research, also in research-based artistic interventions research questions should point to the appropriate mix of methods, never the other way around.

12) Here, my musings are extremely preliminary and partial. I am acutely aware of the fact that ethics in artistic interventions is a complex topic that deserves a conference on its own.

References

Böhme, Gernot 2012. “Contribution to the Critique of the Aesthetic Economy Atmospheres of Seduction: A Critique of Aesthetic Marketing Practices.” Journal of Macromarketing. June 1, 2012 32. pp. 168–180.

Borgdorff, Henk 2009. Artistic Research within the Fields of Science, Sensuous Knowledge Publication Series. Focus on Artistic research and Development, No 06, Bergen National Academy of the Arts, 2009.

Cottrell, Stella 1999. The Study Skills Handbook. Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Gardner, Howard 1983. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York: Basic Books.

— 1993. Multiple Intelligences: The Theory in Practice. New York: Basic Books.

— 2000. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. New York: Basic Books.

Gergen, Kenneth 1999. An Invitation to Social Constructionism. London: Sage Publications.

Hautamäki Antti & Oksanen Kaisa 2011. Tulevaisuuden kulttuuriosaajat: näkökulmia moderniin elämään ja työhön. [Cultural Professionals in the Future: Perspectives on Modern Life and Work]. Committee for the Future, Parliament of Finland, Publications 5/2011.

Hawk, Thomas F. and Shah, Amit J. 2007. “Using Learning Style Instruments to Enhance Student Learning.” Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education. Vol. 5, January 2007. pp. 1–19.

Heinsius, Joost & Lehikoinen, Kai (eds.) 2013. Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts. Kokos Publications 2, Helsinki: Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki.

Hempel, Gerda & Rysgaard, Lisbeth 2013. “Competencies – in real life.” In Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts. Kokos Publications 2, Helsinki: Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, Ch. 3.

Honey Peter & Mumford Alan 1992. The Manual of Learning Styles. 3rd edition. Maidenhead: Peter Honey Publications.

Kolb, David 1984. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Kotler, Philip & Caslione, John A. 2009. Chaotics. The Business of Managing and Marketing in The Age of Turbulence. AMACOM.

Kupias, Päivi 2001. Oppia opetusmenetelmistä. Helsinki: Educa-Instituutti Oy.

Lehikoinen, Kai 2013a. ”Qualification framework for artists in artistic interventions.” In Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts. Kokos Publications 2, Helsinki: Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, Ch. 4.

— 2013b. “Training Artists for Innovation: Guidelines for Curriculum Development.” In Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts. Kokos Publications 2, Helsinki: Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, Ch. 5.

Leite, Walter L., Svinicki Marilla & Shi, Yuying 2009. “Attempted Validation of the Scores of the VARK: Learning Styles Inventory With Multitrait–Multimethod Confirmatory Factor Analysis Models.” Educational and Psychological Measurement. April 2010, 70. pp. 323–339.

Niemi, Merja 2012. Luova talous työssä – miten työelämää voidaan kehittää taiteiden ja kulttuurin avulla ja päin- vastoin: Taide- ja kulttuuritaustaisen osaamisen hyödyntäminen työelämän kehittämisessä. [Creative Economy at Work – How working life can be developed by the means of arts and culture and vice versa]. Report: Ministry of Education and Culture, Finland. 31.5.2012.

Pine, Joseph and Gilmore, James 1999. The Experience Economy, Harvard Business School Press, Boston.

Rantala, Pälvi 2011. ”Taidelähtöisiä menetelmiä työyhteisöihin: prosessianalyysi.” In Anu-Liisa Rönkä, Ilkka Kuhanen et al. (eds.) Taide käy työssä: taidelähtöisiä menetelmiä työyhteisöissä. Lahden ammattikorkeakoulun julkaisu Sarja C Artikkelikokoelmat, raportit ja muut ajankohtaiset julkaisut, osa 74, Lahti: Lahden ammattikorkeakoulu. pp. 16–29.

Rifkin, Jeremy 2000. The age of access: The new culture of hypercapitalism, where all of life is a paid-for experience. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam.

Sahlberg, Pasi & Leppilampi, Asko 1994. Yksinään vai yhteisvoimin? Yhdessä oppimisen mahdollisuuksia etsimässä. Helsinki: Yliopistopaino.

Schiuma Giovanni 2011. The Value of Arts for Business. Cambride: Cambridge University Press.

Vondracek, Anna 2013. “‘Training artists for innovation’ – why, what and how?” In Joost Heinsius & Kai Lehikoinen (eds.) Training Artists for Innovation: Competencies for New Contexts. Kokos Publications 2, Helsinki: Theatre Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki, Ch. 2.

Electronic references

Arvokas työelämä. Available at: www.luovasuomi.fi/soveltavataide/arvokastyoelama, (accessed 12.4.2013).

Berthoin Antal, Ariane 2011. Managing artistic interventions in organisations: a comparative study of programmes in Europe. Gothenburg: TILLT Europe. Available at: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-267627, (accessed 27.9.2012).

Berthoin Antal, Ariane & Strauß, Anke 2013. Artistic interventions in organisations: Finding evidence of values-added. Creative Clash Report. Berlin: WZB. Available at: www.creativeclash.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Creative-Clash-Final-Report-WZB-Evidence-of-Value-added-Artistic-Interventions.pdf, (accessed 12.4.2013).

Bureau of European Policy Advisers 2011. Empowering people, driving change: Social Innovation in the European Union. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/bepa/pdf/publications_pdf/social_innovation.pdf, (accessed 14.4.2013).

Connexiones improbables. Available at: http://conexionesimprobables.es/pagina.php?m1=185&id_p=331, (accessed 20.2.2013)

Cox, George 2005. Cox Review of Creativity in Business: building on the UK’s strengths. Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/+/http:/www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/coxreview_index.htm, (accessed 6.1.2013).

Davis, Ian 2009. The new normal. The McKinsey Quarterly. March 2009. Available at: www.washburn.edu/faculty/rweigand/McKinsey/McKinsey-The-New-Normal.pdf, (accessed 27.2.2013).

Hempel, Gerda (ed.) 2010. 15 Cases Artists & Businesses: People in the innovation & experience economy. Available at: http://artlab.dk/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/artlabcases_uk.pdf, (accessed 20.2.2013).

Korhonen, Satu-Mari 2012. Taidelähtöiset interventiot henkilöstön ja organisaation kehittämisessä. In Satu-Mari Korhonen & Pälvi Rantala (eds.) Uutta osaamista luomassa – Työelämän kehittäminen taiteen keinoin. Lapin yliopiston yhteiskuntatieteellisiä julkaisuja ja selvityksiä, 61. Rovaniemi: Lapin yliopisto, pp. 25–30. Available at: www.taikahanke.fi/binary/file/-/id/4/fid/1253/, (accessed 19.2.2013).

Murray, Robin, Caulier-Grice, Julie & Mulgan, Geoff 2010. The Open Book of Social Innovation. NESTA & The Young Foundation. Available at: www.nesta.org.uk/library/documents/Social_Innovator_020310.pdf, (accessed 14.4.2013).

Pässilä, Anne 2013. A reflexive model of research-based theatre. Processing Innovation at the Crossroads of Theatre, Reflection And Practice-Based Innovation. Doctoral Thesis. Acta Universitatis Lappeenrantaensis 492. Lappeenranta University of Technology. Available at: www.doria.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/86216/isbn%209789522653222.pdf?sequence=1 (Accessed 14.4.2013).

The Ministry of Employment and the Economy 2012. Työelämän kehittämisstrategia vuoteen 2020 [Working life development strategy 2020]. Available at: www.tem.fi/index.phtml?s=4698, (accessed 12.4.2013).

The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland 2010. Sosiaalisesti kestävä Suomi 2020: Sosiaali- ja terveyspolitiikan strategia [The Socially Sustainable Finland 2020: The Strategy of Social and Health Politics]. Available in: www.stm.fi/julkaisut/nayta/-/_julkaisu/1550874, (accessed 13.4.2013).

TILLT. Available at: www.tillt.se/kunduppdrag/ericsson-ab, (accessed 20.2.2013).

Wikipedia. Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Art_intervention, (accessed 5.1.2013).