Abstract

During 2010–12 I have been working with an artistic development project, exploring the theme silence, related to my own practice as a director with a laboratory theatre background. My exploration has included questions on the director’s work process, position and communication with actors in collaborative situations, the presence of personal themes in the artistic work and the investigation of silence as a specific awareness and approach to the world. In 2011 a performance act, Silent Walk, was presented in urban public space, raising new questions and areas of exploration into the project. It put the relation between actor and spectator to a head and evoked questions on the ethical aspect of the human encounter. The project has produced different artifacts and documents: performances, texts, soundtracks, performance-lectures and a short film. A complex weave of questions, threads and documents has started to grow around the project.

Introduction

During 2010–12 I have been working with an artistic development project at the Academy of Music and Drama in Gothenburg, investigating my own practice as a director.(1)The complete title is Postdramatic Theatre as Method and Practical Theory Inside and Outside of Academia. The project was carried out in two parts, one was led by me in collaboration with Helena Kågemark, and another part was led by my colleague, the choreographer Pia Muchin, in collaboration with the actress Gunilla Röör. The starting point for my part of the project was to explore working methods and central concepts in physical theatre, with my own practice as an example. The aim was also to relate this exploration to the ongoing debate on post dramatic theatre that was active in the Swedish theatre at this particular time. After several years as a teacher and supervisor at the theatre academy in Gothenburg I felt an urge to put myself under the magnifying glass.

My practice as a director has been linked to or influenced by research in different ways. This has to do with my own background in laboratory theatre (and it’s focus on acting research) but also in performance studies (my PhD dissertation from 2003 connected theory and artistic practice). My main focus since 2005 has been in the field of artistic research.

This project is divided into different parts and contains a rich material. Today I will give you a brief impression of the project’s different areas, and go more into detail in some specific parts of it. I want to make visible my way of exploring and researching that came out of this process, to give a glimpse of the many different approaches and methods that are present.

Quite soon, after starting the project, I realised that it was dealing with silence. It became obvious for me that I experienced my own practice as being silent. I asked myself why. One aspect had to do with the fact that the tradition of laboratory theatre is a tacit and marginal phenomenon in the history of Swedish theatre. Another aspect dealt with my own muteness regarding my artistic practice in the encounter with the theatre academy, with its strong tradition of realistic text-based theatre. I also perceived silence being present as a method in my work as a director, with its emphasis on listening, observing, composing and collecting. Finally, I realised that for me the most important aspects in art and in life appear in the silent, ambigous and tacit dimension.

I thus identified silence as the red thread in my practice. I decided to explore silence as a theme, in order to gain new perspectives on my artistic practice. The project came to examine the silence from various angles, as a silenced history, as a method of directing, as a search for presence, as a refuge and as a strategy.

I invited my collaborator since many years, the actress and wire dancer Helena Kågemark, to work with me in the project. The fact that she knows me well as a director was important to me in this process. We were discussing performances we had done together in the past and tried to find patterns, we related these to our common background in laboratory theatre (Institutet för Scenkonst). We also started to create performance etudes around the theme silence.

Silence as a method of directing – The director’s silence

In the work with the etudes we sometimes stopped in the middle of rehearsing trying to analyse our actions. What am I actually doing when I direct? How do the actress and I communicate with each other? How are decisions, ideas and suggestions taking shape? We were tracking the development of material and we realised how intertwined all artistic choices really were: how one step on the floor in the studio led to an association that led to a discussion that took the improvisation further… and so on. I realised that an important part of my directing is about listening and observering; it is about what I don’t say. Of course these aspects have a lot to do with the way of working based on improvisations, the process of selecting material and an open searching. It is about a resistance to make decisions too early in the process.

In this theatre tradition the director is labelled an observer. The task of the observer is to listen, wait and recognise what the actor does and make a context out of it, in relation to a spectator.

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Rehearsing

- Stopping and analyzing in the moment

- Making intentions and associations visible

- Observing what is said and what is not said

A silenced history: The Director’s personal theme

Another part of this explorative work circled around a biographical story, my own family history. I did a kind of a detective work around my own silenced Estonian heritage.

(An image with both the Swedish and the Estonian flag appears)

My mother came from Estonia to Sweden during Second World War, when she was only six years old. When I grew up we seldom talked about the Estonian background. We were Swedish. The fact that my mother was born in Estonia and that she and her parents talked Estonian to each other – this secret language my brother and me were never supposed to learn – seemed like an unimportant detail. Many years later, I started to sense that there was something strange with the silence around the Estonian, in my childhood. I started to dig into my family history – one of exile and shame – and the history of Estonia. Through literature (writers such as Oksanen, Kaplinski, Handberg, Kross), interviews with my aunt and a travel to Estonia meeting relatives I had never seen before, I got important keys to a deeper understanding of these aspects.

I started to put these different fragments side by side with images from past performances, directed by me or by my theatre sources. Through activating this biographical story I could see my artistic themes and interests more clearly. There was something of this collective Estonian silence also in me, even if I never lived there. I started to look at my artistic sources of inspiration and my own aesthetics in a new way.

(A slideshow with images of performance work by Institutet för Scenkonst, Etienne Decroux, Jerzy Grotowski and Tadeusz Kantor or by myself is being showed together with an audio quote from Peter Handberg(2)“Där fanns ett segdraget rörelsemönster som jag inte riktigt kunde härleda: kom det från gener, latituder och kulturens långsamma stöpform? Eller av främmande herrars förtryck som med århundradena sipprat in i kroppen och vidare ut i själen? Eller – som de flesta skulle påstå – var det resultatet av de senaste femtio åren med tvångsmarsch under röda fanan? Människorna påminde mig om van Gogh-målningar. Naturligtvis inte koloriten, inte heller motiven. Det var snarare den psykiska energin i målningarna som jag tyckte mig skönja i den estniska vardagen och människan. Ett slags ödsligt tomrum som hypnotiserande sög en in mot dess mitt. (…) Trots allt fanns det något som levde, fast det var överdraget av ett tjockt lager is. Något som ville ut, men som med kraft hölls inne.” “Hämskon var en inre kokpunkt som utåt visades upp som opåverkad stillhet.” Handberg 2008.).

This text was in Swedish by Peter Handberg, quoted from his book Kärleksgraven – baltiska resor. He is commenting on how he experienced the Estonian people when arriving there in the beginning of the 1990s. He is for example describing how the Estonians seemed to possess an inner boiling point presented outwardly as an unaffected stillness, an inner life covered with a thick layer of ice.

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Historical studies

- Literature/fiction

- Biographical studies

- Memories, diaries, objects

- Images from performance work

- Creating a puzzle of fragments from these different sources

Silence as a search for presence

The next perspective on silence that we explored was that of presence. This part was mostly dealing with making visible certain perspectives and practical training techniques we have developed during the years, focusing on the small moments and the attentiveness. This work is inspired by the theatre group Institutet för Scenkonst. We identified this as the searching for a full quality of life in one single moment, and saw a red thread in our theatre tradition: Etienne Decroux’ mime, Jerzy Grotowski’s impulse training, the Institutet’s mutation work. We tried to formulate what we were looking for with the help of others. Here is one example:

1897 Leo Tolstoj wrote the following in his diary:

I was dusting in my room, and when I – on my way through the room – came to the sofa, I couldn’t remember if I cleaned it or not. As the movements were familiar and unconcious I couldn’t recall, and I felt that it was already impossible to do so. So, if I had already dusted there and forgotten, if I had acted unconsciously, it would have been the same as if it never happened. If somebody had seen it and was aware of it, it could have been determined. But if nobody had seen it or if somebody had seen it without being aware of it; if the entire assembled life passes by unconsciously for many people, it is as if this life had never existed.(3)My translation from the Swedish version: ”Jag höll på att damma i mitt rum, och då jag på min rond genom rummet kom till soffan, kunde jag inte komma ihåg om jag dammat av den eller inte. Eftersom rörelserna var invanda och omedvetna kunde jag inte erinra mig det, och jag kände att det redan var omöjligt att göra det. Så att om jag redan hade dammat där och glömt det, dvs. om jag handlat omedvetet, så skulle det vara precis detsamma som om detta aldrig hade varit. Om någon hade sett det och var medveten om det, skulle det kunna fastställas. Men om ingen hade sett det eller hade sett det utan att vara medveten om det; om hela det sammansatta livet för många människor går omedvetet förbi, så är detta liv som om det aldrig varit.” Retrieved from my dissertation: Lagerström 2003.

We developed a demonstration of this kind of work, an exercise of taking one single step. The actress demonstrated the process of taking one step, simultanously talking “from the inside” commenting what was happening in the moment. It was a deconstruction of one life moment on a micro-level. The demonstration was being placed in a performative situation – it was shown in the frame of a performance – thus challenging the border between reality and art.

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Making visible training techniques on stillness

- Trying them out in performative situations

- Making a deconstruction of one moment, simultaneously commenting from the inside (reflection-in-action)

- Using and questioning concepts of “presence”

Silence as a refuge

The next part was dealing with silence as a refuge, and it played around with different kinds of material. Ethnographic research on the reasons for certain groups in society to be more quiet than others was followed by research on noise problems in the city, making people disabled and ill. The short story by the Austrian writer Heinrich Böll Dr Murkes samlade tystnad (Murke’s Collected Silences) became important. Dr Murke is working at the radio and is collecting pauses and silences that have been edited from different radio recordings. He brings them together on a tape that he listens to in the evenings at home. The silence becomes a kind of a refuge, growing from the gaps and the transitions between the past and the future, and an abundance of talk, with or without meaning.

– Tystnad. Jag samlar tystnad. När jag klipper ett band där det förekommer en och annan paus – eller suckar, andetag, absolut tystnad – så kastar jag inte klippen i papperskorgen utan tar vara på dem.

– Och vad gör Ni med bitarna?

– Jag klistrar ihop dem och spelar upp bandet när jag kommer hem på kvällen. Det är inte så mycket än, jag har knappt tre minuter – men det är ju inte heller så ofta det hålls tyst.

– Jag måste göra er uppmärksam på att det är förbjudet att ta band eller delar av band med sig hem.

– Tystnad också?(4)Quoted from the short story and used as dramatic text in the research performance “Etudes on Silence”.

We started to question our own longing for and interest in silence, when exploring these different sources. Is silence a refuge? From the corrupted language and human actions? Is it all about a skeptical attitude towards language and the possibilities of understanding that developed after the Second World War? Or is it a dream about an absolute silence that we can never realise but only imagine?

(Our version of Dr Murke’s tape is heard in the speakers).

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Research on noise and silence from sociological and ethnographic perspectives

- Literature/fiction on noise/silence (metaphorical level)

- Exploring different kinds of sonic silences and pauses in practice (editing Dr Murke’s tape)

- Critique of cognitive perspectives or “the-here-and-now-concept”

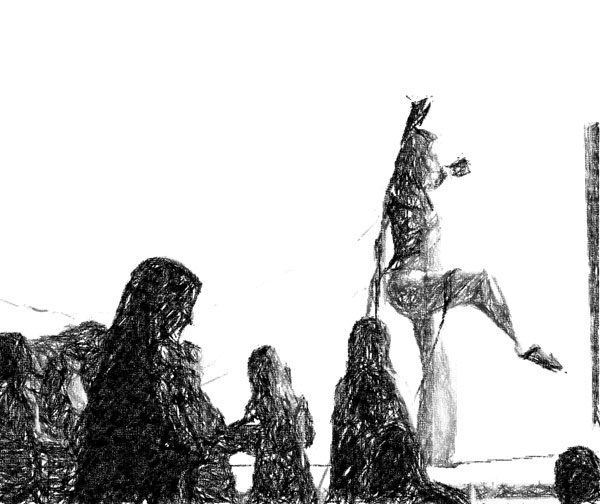

A Research Performance

In 2011 I directed a research-performance “Etudes on Silence”. The research performance is a genre I tried out for the first time in 2005, where artistic scenes blend with the presentation of the research in question, and where lecturing, acting, film showings, discussing and so on is presented as an artistic form / a performance in itself. In the performance I included much of the material and perspectives I have already touched upon. I also included one more actor, a young male actor, Rasmus Lindgren from Backa Theater in Gothenburg. He performed the role of me, Cecilia the director, while I was present on stage as Cecilia the researcher. Staging myself through an actor was another way of trying to see myself from a distance, to hear my words from another person’s mouth and getting some resistance and questioning. In one part of the performance Rasmus and Helena did a reconstruction of a rehearsal situation between Helena and me without my involvement.

(A short scene with Helena and Rasmus from a filmed documentation of the performance is being screened).

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Exploring the research material by performing

- Presenting research material by performing

- Staging myself as the researcher-director (creating distance and different perspectives)

Silence as a strategy

We are arriving at the last part of the project, silence as a strategy.

We intended to try out a strategy of silence in a situation of noise, to test a contemplative approach, facing rumbling surroundings. We also wanted to test our exploration of silence, in a situation in which we rarely find ourselves, to present an unannounced and uncommissioned performance act in the public space. We needed to meet others – people from outside of an artistic context. In October 2011 I directed a performance act with Helena titled Silent Walk.

(The shortfilm Silent Walk is being screened in the background, without sound)

In this act, Helena is walking very slowly through the central parts of Gothenburg in the rush hour, dressed in a smart suit with her face painted white. The slowness and the silence in her walking, together with her white face, were features that created a deviant pattern amongst the fast walking people in the crowd. The purpose of the act was to create a reminder of “something else” for the involuntary audience in a place marked by consumerism, high speed and people on their way. Helena had a specific path to follow, which we had worked out in advance. She did not consciously search for contact with bypassers, but she was looking around observing her surroundings. She walked slowly, focusing on her perception, inwardly and outwardly. An important basis for performing the act is the quality of her presence.

Maybe the most apparent thing with peoples’ ways of receiving the act was the plurality of reactions: Cries of delight, smiles, embarrassment, angry outbursts, scornful comments and silent observation. The actress observed the people and their reactions, seemingly without responding. She did not mirror her fellow beings or interact with them, but continued her slow, metered walk. This behaviour in itself seemed to result in certain reactions of provocation, anger, compassion or playfulness.

The intention was that Helena, the woman, would function as a reminder for people in their everyday flow of life. She was someone who walked around and listened to, or overheard, the world; not dissimilar to the angel in Wim Wender’s film Wings of Desire. She encountered what occurred around her without judging or interfering. This resulted in peoples’ reactions and answers often bouncing back on them, as if the actress became a projection screen for the spectator’s own story. The possibilities of interpretations of the act seemed endless.

At one of the performances of Silent Walk we experienced unexpected encounters with bypassers, a group of children and some teenagers. They started to follow Helena filming her with their smartphones. They tried out different strategies in order to mock her and to disturb her walk. The actress became a prey, an object. There were two aspects that broke the objectification and the aggressive approach, the gaze and the perception of risk. When she looked the young persons into their eyes they suddenly backed out and were unarmed. – “She looked me straight into the eyes, scary.” For an instant she became human. When she was on her way out into the traffic, over the crossroads at Drottningtorget (The Queen’s square), some of the young men started to walk with her. They were now walking at her pace, at her breathing.

After performing Silent Walk, the philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas’ ideas on the ethics of the face emerged. Spectators’ strong reactions on the performer’s gaze and face, and the very disparate, sometimes violent, responses that arouse activated Lévinas ideas in our work:

Lévinas’ analysis of the cry emanating from the face of The Other is central in modern ethics, but increasingly forgotten by the modern man. This face, which cannot be owned, nor become a prey possible to subdue. The face belongs to somebody else; it comes from the outside as something totally strange. And at the same time, it is my own face. Naked and vulnerable. Deep inside the gaze of the other, something tells us about our common feeling of being lost, our search, our vulnerability, our fear of violence, for extermination – and our obstinate aspiration to find a place in this ambiguous existence. (Retrieved from Kaltiala 2011, my translation.)

We experienced something both significant and disturbing in the encounter with Lévinas’ thoughts. This raised questions on the inter-human encounter. Are we able to encounter the Other without imposing our own view of the world onto him or her; without making the Other into us, into me? Are we able to accept the unfamiliar without reducing it? Emmanuel Lévinas gives the Other and the gaze of the Other a central position. In meeting another being, one’s own horizon is challenged, and therefore we are constantly looking for ways of eliminating the face of the other, to make it ours. Only through an acceptance of the gap between me and the other person, of that which is not me, can a real encounter take place. (Lévinas 1987.)

Silent Walk triggered situations we had never anticipated, and provoked responses that surprised us. This opened up for several new areas of investigation, dealing with the encounter with the Other, the ethics of the face and other aspects related to public space. This could be the beginning of a new research project. The experiment tried out our work in a direct encounter with people in public space, making visible both our way of creating an act and our approach to the spectator, the Other. For me it gave new perspectives on the role of art in society and my own theatre work.

(This section on Silent Walk is shortened, as part of this material is due to be published elsewhere soon).

Summing up methods of exploration:

- Creating a performance act – staging silence

- Placing the work in a different context than usual

- Philosophy of ethics

- Testimonies:

- Writing and drawing journals/work diaries

- Written reflections from a few invited spectators

- Discussions with spectators in the situation

- Film documentation

Concluding words

I have intended to give a glimpse of how this project shaped it’s own dramaturgy, trying out different angles on the theme silence. The project explored a specific practice, my own, with its’ links to a theatre heritage, but it also investigated questions beyond this. Such questions were dealing with the search for presence, the carrying of supressed stories or what it means to encounter the Other. Today I have presented these topics as separate sections of the project, but in the work process they were to a great extent fused or overlapping. One thing went into the other and angles were connected. A complex weave of questions, threads and documents has started to grow around the project. Many different artefacts and documents have been produced. I regard the multitude of different approaches as a value in itself and I would like to argue for a research perspective that embraces this complexity.

Bio

Cecilia Lagerström is a director, artistic researcher and senior lecturer at the Academy of Music and Drama at the University of Gothenburg (Sweden). She has a background in laboratory theatre and has a PhD in Performance Studies. Since many years she has been directing performances in theaters and other venues, and artistic research-and-development projects at the universities in Stockholm and Gothenburg. She teaches and supervises at masters and doctoral level in the performing arts.

Notes

1) The complete title is Postdramatic Theatre as Method and Practical Theory Inside and Outside of Academia. The project was carried out in two parts, one was led by me in collaboration with Helena Kågemark, and another part was led by my colleague, the choreographer Pia Muchin, in collaboration with the actress Gunilla Röör.

2) “Där fanns ett segdraget rörelsemönster som jag inte riktigt kunde härleda: kom det från gener, latituder och kulturens långsamma stöpform? Eller av främmande herrars förtryck som med århundradena sipprat in i kroppen och vidare ut i själen? Eller – som de flesta skulle påstå – var det resultatet av de senaste femtio åren med tvångsmarsch under röda fanan? Människorna påminde mig om van Gogh-målningar. Naturligtvis inte koloriten, inte heller motiven. Det var snarare den psykiska energin i målningarna som jag tyckte mig skönja i den estniska vardagen och människan. Ett slags ödsligt tomrum som hypnotiserande sög en in mot dess mitt. (…) Trots allt fanns det något som levde, fast det var överdraget av ett tjockt lager is. Något som ville ut, men som med kraft hölls inne.” “Hämskon var en inre kokpunkt som utåt visades upp som opåverkad stillhet.” Handberg 2008.

3) My translation from the Swedish version: ”Jag höll på att damma i mitt rum, och då jag på min rond genom rummet kom till soffan, kunde jag inte komma ihåg om jag dammat av den eller inte. Eftersom rörelserna var invanda och omedvetna kunde jag inte erinra mig det, och jag kände att det redan var omöjligt att göra det. Så att om jag redan hade dammat där och glömt det, dvs. om jag handlat omedvetet, så skulle det vara precis detsamma som om detta aldrig hade varit. Om någon hade sett det och var medveten om det, skulle det kunna fastställas. Men om ingen hade sett det eller hade sett det utan att vara medveten om det; om hela det sammansatta livet för många människor går omedvetet förbi, så är detta liv som om det aldrig varit.” Retrieved from my dissertation: Lagerström 2003.

4) Quoted from the short story and used as dramatic text in the research performance “Etudes on Silence”.

References

Kaltiala, Nina 2011. March 18. “Därför måste vi låta oss störas av den Andre”. Dagens Nyheter.

Lagerström, Cecilia 2003. Former för liv och teater. Institutet för Scenkonst och tyst kunnande (Forms of Life and Theatre. The Institute for Stage art and tacit knowing). Hedemora: Gidlunds.

Lévinas, Emmanuel 1987. Time and the other: and additional essays. Pittsburgh, PA: Duquesne University.

Böll, Heinrich 1960. “Dr Murkes samlade tystnad” (Murke’s Collected Silences). In Doktor Murkes samlade tystnad och andra satirer, Stockholm: Bonnier.

Handberg, Peter 2008. Kärleksgraven. Baltiska resor (The love grave. Baltic journeys). Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

Images by Johanna St Michael and Cecilia Lagerström.