Writing sites of silence

I will take my recently completed spoken-word performance work Between Our Words I Will Trace Your Presence – from which I will perform an excerpt – as the starting point for discussing the place of writing in my work. Specifically, I will explore my artistic research’s capacity to examine different sites of silence; familial, textual and institutional. My work deals with silence not as a sensate phenomenon, but as something relational; something enacted or performed, founded in acts of repression and denial; its character always specific to a given set of circumstances, but always characterised by the presence of something unspoken or unheard. In my examination of such silences, I have found myself adopting strategies which draw on Jane Rendell’s model of ‘site writing’. Also developing a mode of autofiction writing, which is informed by Mona Livholts’ conception of a ‘situated writing’ practice and which lays emphasis on insights localised in the writing-subject’s position. Together, these approaches create a writing subject, whose presence and experience are central to the creation of both site and knowledge. My writing also aspires to a performative – as opposed to an expositional – agency and through spoken word performances, I have been performing my writing. In this presentation, I will discuss my writing practice and introduce the issues raised by the proposition that my writing and my performance of my research have the potential to create distinctive relationships between researcher, knowledge and audience.

I want to focus on the emergent part played by writing in my work; specifically, its role in making legible the silences which my practice has begun disclosing at different orders of site. My writing emerges in response to my experience of site, and a diversity of different relationships between site and writing have in turn emerged as important to my reflection on my practice. Jane Rendell’s notion of ‘site writing’ provides a useful reference-point in exploring that practice. Rendell describes site writing thus: ‘a critical and ethical spatial practice that explores what happens when discussions concerning situatedness and site-specificity enter the writing of criticism, history and theory’ (Rendell 2019–2022). My own work has suggested an ever-expanding definition of what the notion of site can encompass, which reflects Rendell’s proposition that sites may include those ‘material, political and conceptual – as well as those remembered, dreamed and imagined’ (ibid.). I will examine several instances of my writing in response to site, and consider the role of that writing in each case; it’s relationship to site, to ‘situatedness’, to performance and to knowledge production.

1/. The University of Bergen Natural History Museum

Silence in my understanding may be performed or enforced. For my work, silence encompasses the notion of being silent; that is, leaving things unspoken, or equally of being silenced; also embracing the idea of a silence created by the act of not hearing; not having heard. In other words, a denial that one has heard. Crucially, in each case, the silences with which I’m concerned are revealed not as sites of absence, but as sites of repressed presence.

In making my work, I’ve found myself inhabiting different silences at different kinds of site. In the first instance, an example of an institutional silence; that found at the university’s natural history museum, in Bergen, Norway. The “object” of the institutional silence I identified here concerns the presence of the museum’s ‘wrong bodies’; the bodies of pests and insects in the museum’s midst, which ordinarily remain absent from the institution’s public discourse, but with which the museum has a covert, complex relationship; gathering and cataloguing their captured carcasses to create a curious private analogue of its public collection.

Although the presence of these wrong bodies within the museum is ordinarily a matter of public silence, their history is charted in informal, typically anecdotal, subordinate and marginal narratives, shared amongst museum staff, across generations. I was drawn to these marginal narratives, including accounts of events in 1979, when the museum was compelled to react to a particularly invasive insect infestation in a dramatic manner, which forced the presence of its “wrong bodies” into the public realm.

After gathering and compiling verbatim transcripts of eyewitness and anecdotal accounts of these events, with the permission of my contributors, I began to rework them into a vivid polyphonic narrative, which became a part of a planned, spoken-word performance, to be staged at the museum, and titled ‘The Wrong Bodies’. Here is an excerpt from that narrative:

The eye witness: They made a coat of plastic, Imagine what it took. They made a coat of plastic for the whole house. That was the first time I saw something like that and I couldn’t believe what I saw. I couldn’t believe my own eyes. It was very neatly done too, as these things are. I don’t know how they did it, but it was beautifully done, and it looked so ridiculous and we laughed.

The curator: It was 1979 and they were having an infestation of museum beetles; small beetles that eat up all the organic tissue on museum specimens. At one point it was decided that to get rid of these museum beetles, they had to wrap up the museum and fumigate the place.

The eye witness: They used this Blåsyre, which I think is Zyklon B. And it said in the newspaper, “the work has been going well”. “The work has been going well and they have been using Blåsyre”.

The curator: They wrapped the museum in plastic and put boxes of this gas in every room in the museum… They wrapped the museum in plastic, opened the boxes and let the gas come out, naturally. When the fumigation had run its course… When the fumigation had run its course and supposedly all the beetles were dead… When the fumigation had run its course and supposedly all the beetles were dead, they had to slowly start unwrapping the museum. And from what I’ve been told as soon as they started unwrapping the building… As they started unwrapping the building, a lot of the gas that was still remnant in the building came out. A lot of the gas that was still remnant in the building came out and apparently, birds… fell from the sky. Birds that were flying over the museum fell from the sky, because of the gas that was still escaping. The birds… fell… from the sky.

As an artist working with writing; responding to site, here I became an amanuensis, and a curator; an editor, re-worker and animator of these narratives.

In these images we can see the space in the museum designated for the work’s spoken word performance. A performance so far unrealised due to the current pandemic. My aspiration was to use the writing with which I was working, animated by performance, to make manifest the ordinarily unacknowledged – unspoken – presences within the institution, that had been disclosed by my work.

2/. The Green Line, Nicosia, Cyprus

I’ve become interestedin the performance of my writing as a means of mediating the relationship between site and writing, and on account of its potential to draw writing into what Salomé Voegelin, has described – in reference to her own often improvisational work with texts and other media – as an ‘ambiguous and unreliable sphere’ (Voegelin 2019).

In the case of the performance of the The Wrong Bodies, the work described above, writing and site have a clear and explicit a priori relationship. Quite a different conjunction of my writing and site took place in 2019, when I took an iteration my text work, Between Our Words I Will Trace Your Presence, to the Nicosia Buffer Fringe Festival, on the communally divided island of Cyprus. Once again here, my writing was used to activate a space, but with quite different consequences.

Over an intense forty-eight hours, I devised a performance wherein Between Our Words… – a text which comprises a meditation on the repressed, the unspoken and unheard in my own familial history; interwoven with silences drawn from selected literary and cinematic works -was read aloud in the island’s UN Buffer Zone; the demilitarised, liminal and ordinarily depopulated space, that has for many decades run through the heart of Nicosia, partitioning Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities.

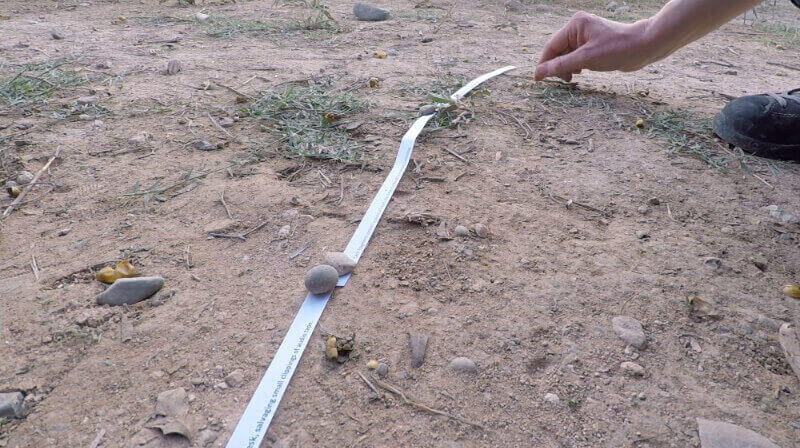

As I performed Between Our Words…, the words of my performance, laboriously printed line by line on flimsy paper, were laid out in the dirt of the Buffer Zone. The performance, its audience, the trail of printed text, and the repressed and disavowed presences concealed in the silences disclosed by the text traversed and briefly inhabited the historical, material and geo-political “gap” in the life of the city, created by the Zone’s interstice. The text, like the Zone itself, comprised of apparent lacunae, that are not empty at all, but are instead each freighted with the weight of their own histories.

When responding to site through writing, language matters, and in hindsight that is nowhere more true, than in this instance. The decision to inscribe a text in English, into the earth of the Buffer Zone is not inconsequential or neutral. It is arguably no less historically and politically loaded than writing here using Greek or Turkish words. This observation provides me with a timely check; a reminder and admonition regarding a necessary sensitivity to the importance of language itself, in relation to site. At the same time, my reflection on the Nicosia work emphasises the possibility of using writing and performance to actively explore the political and historical nuances of (different) languages, in relation to a given site.

3/. Heinrich Böll’s Doktor Murkes Gesammeltes Schweigen and Yasujirõ Ozu’s Late Spring

The sites to which my own work has returned a response, have expanded to include particular cinematic scenes; events described in literature and poetry and the materiality of certain literary texts. The first, and possibly the most significant literary site of silence for my research remains Heinrich Böll’s 1955 satirical short story, Doktor Murkes Gesammeltes Schweigen (Murke’s Collected Silences), which offers – through the activities of its eponymous protagonist – the model of a compulsive collector of silences. Murke is a radio producer who hoards the pauses, gaps, hesitations and lacunae committed to audio-tape during the production of radio broadcasts on which he works.

I found in Murke an echo of my own compulsions, and in my creative writing, I began using him as a cypher or persona – “the collector of silences” – through whom I could both explore the notion of collecting silences and, as my work developed, my own fascination with doing just that. The character of Murke, expanded from Böll’s original, has appeared repeatedly in my writing; for example, in my 2019 work, Between Our Words I Will Trace Your Presence. What follows is a short excerpt from that work, in which my own writing creatively re-imagines Murke’s relationship to the silences with which he is obsessed in Böll’s original text; allowing me to reflect more broadly on the significance of the unspoken and the unheard, both for Böll’s writing and my own research.

“Berlin, 1955. Evening, and the building around him is quiet, the office workers long departed. High above, the empty cars of a paternoster lift circulate, endlessly. Far below, in rooms insulated from the sounds of the city; occupying a world in parenthesis, Murke, the radio producer runs his hand over the surface of a studio console, salvaging small clippings of audio tape.

Each fragment contains a pause, a breath, the shape of a thought. Each represents a hesitation, a withholding; a lacuna, edited out from some or other speaker’s utterances. He sweeps the clippings into a small tin. Pockets it. Later, he will splice these fragments together, to create a recording composed not from words, but from the gaps between them. Now, he sits alone, reflecting that he has covertly become a collector of silences, in a country and at a time where every silence is like an unexploded bomb, peopled not by absence, but by presences denied.”

Although this work can still be understood within the broad definition of site writing proposed by Rendell, my role here as an artist working with writing, is in some respects qualitatively different to that I adopted in relation to the Natural History Museum. Having said that, my use of the character, Murke, as a cypher through which to articulate my own preoccupation with collecting silences, is in some respects only a alternate strategy with the same end in mind, when compared to my utilisation of the anecdotal and eyewitness accounts I gathered about the museum’s silences.

The use of such a cypher does however offer an intimation of a direction of travel which has led me to consider my own family history as a site of silence and in doing so, to adopt a form of writing in the third-person about my experience, which owes something to Serge Doubrovsky’s notion of autofiction; denoting writing which is neither straightforwardly fiction or autobiography.[1] My autofiction is also informed by Mona Livholts’ practice of situated writing; a practice, which Liz Stanley defines in her foreword to Livholts’ 2019 book, as ‘a form of reflexive autobiography mixed with story-telling which exemplifies as well as promotes its claims in terms of situated knowledge’ (Livholts 2019, viii). Livholts’ situated writing thus suggests a basis for knowledge production, through writing, which like that developed in my autofiction, embraces the value of an overtly situated, partial, localised subjectivity.

- [1] See Dix 2018, for an account of autofiction in English language writing.

In adopting these strategies to address my preoccupation with the silences and repressions which characterise my work, through my own history, I have also found myself embracing Jane Rendell’s injunction that those working with site writing: ‘reflect on their own subject positions in relation to their particular objects and fields of study’ (Rendell 2019–2022).

4/. Between Our Words I Will Trace Your Presence: family history, autofiction and situated writing

The autofictional component of my writing has been based primarily on identifying my relationship with my father, who at the end of his life, lived with dementia, as a site for interrogation. My writing has allowed me to weave my responses to Murke’s story and other literary and cinematic sites of silence, repression, withholding and disavowal,[2] with my own experience of the historical and more recent silences, that did much to shape my relationship with my father.

- [2] In writing Between Our Words…, in addition to Böll’s story, the other, “mediated” sites of silence that I drew on, and interwove with my own experience, included Ilya Kaminsky’s collection of poetry, Deaf Republic, the story of a population who enter into a self-induced deafness of denial as an act of defiance, in a situation where to hear is to become complicit; the nexus of histories and associations represented by Jonathan Safran Foer’s die-cut book, Tree of Codes (a redacted text based on Bruno Schulz’s short stories, originally published as The Street of Crocodiles) and scenes from Yasujiro Ozu’s 1949 film Late Spring.

Here is a short excerpt from that writing.

The son arrives at his father’s house in the early afternoon, noticing that the garden is beginning to fill with weeds. The house as he enters it, is quiet, but he senses his father is there, inside.

He will talk to the old man, today. Will tell him, at last, that instead of a recollected childhood of words exchanged, it is all the words withheld, that he now remembers: the frequent spells when he, the father, withdrew and would not speak either to the son or to his wife.

Living as he does these days amid other, ever-growing gaps, it is doubtful whether the father can remember those earlier interruptions in the discourse of family life, but as a child, the son had lived amongst the silences his father had created, had inhabited the gaps produced by the father’s withdrawal.

Silence breeds silence and the son imbibed the father’s habit, became practiced himself in the art of withholding, until non-disclosure became a way of life. Was more the father than he cared to know; answered silence with silence, became the man; reserved.

“Why did you behave this way?”, the son will ask his father now, but the old man will not, cannot answer and will only look at him questioningly. It is safe to ask now, because there will be no answer, only further silences.

Growing to adulthood, the son found himself compelled by encounters, which somehow spoke to his own memories of earlier, incomprehensible silences; discovering their echo in other, unexpected places; experiencing a frisson of recognition each time he did so.

He too became a connoisseur of gaps, of intervals; all the while, drawn to discover what might be found therein. His compulsion leading him to recently vacated rooms, where absences hung quietly like over-coats, expectant, waiting to be claimed.

Where once the son had perceived only absence, only silence, he now found that both had form; that the silences between lovers were not equivalent; superficially identical, they were capable of signifying both deep contentment or separation and loss.

He understood that conversation was created as much from the gaps between words as by the words themselves and if a conversation, then why not a text. If a conversation, then why not a human life?

Home: the template for all the silences, all the gaps that followed. He, the son, has come home, to a site that for all its familiarity, is nonetheless the hardest to perceive.

Even as he sits with his father, unspeaking, holding the old man’s hand, father and son both drifting back to their respective childhoods, fresh silences begin to emerge between them: an ever-growing, untraversed terrain and the son reflects that far from framing absence, these silences are freighted with all that remains unsaid; all that is now unutterable between the two.

It was through this autofiction, which is central to Between Our Words… that I was able for the first time, to acknowledge and explore the depth of the autobiographical roots of my own interest in silence, and in so doing to understand how my own subject position is central to the way in which my practice operates to generate insights and new knowledge. In encountering Livholts’ notion of situated writing, I have in turn, been able to begin to articulate a potentially useful relationship between my own evolving writing practices and a wider tradition of knowledge production, which acknowledges the importance of writing from a specific somewhere. At the same time, I find in Salomé Voegelin’s practice of drawing texts into the speculative and uncertain sphere of performance, an intriguing parallel for my own tentative attempts to use performance, to mediate the relationships between writing and site, in my own practice.

References

Böll, Heinrich. 1986. “Murke’s Collected Silences.” Translated by Leila Vennewitz. In The Stories of Heinrich Böll. Northwestern University Press.

Dix, Hywel. 2018. Autofiction in English. Palgrave Macmillan.

Foer, Jonathan Safran. 2010. Tree of Codes. Visual Editions.

Kaminsky, Ilya. 2019. Deaf Republic. Faber & Faber.

Livholts, Mona. 2019. Situated Writing as Theory and Method: The Untimely Academic Novella. Routledge.

Ozu, Yasujirõ, dir. Late Spring. BFI, 1949.

Rendell, Jane. 2019–2022. “Site Writing.” https://site-writing.co.uk.

Voegelin, Salome. 2019. “Curatorial Performances.” https://www.salomevoegelin.net/curatorial-performances.

Contributor

Andy Lock

Andrew Lock is an artist, researcher and educator. Andy Lock is currently an assistant professor at the University of Bergen’s faculty of Fine Art, Music and Design, where between 2016 and 2020, he was a Research Fellow. He has exhibited internationally and his current artistic research has appeared through commissions, presentations, exhibitions and other events, in Germany, Sweden, Cyprus and Norway since 2016; most recently published as part of Fluid Territories (2020), Sandborg et al.