Brain machine dérive

With this game performance, we aim to introduce a new form of technological writing in artistic research. We apply the technical settings of the actual Status Quo of Artificial intelligence in writing, generative neural network models. We use a certain “ludic method”, a concept developed within the Ludic Society project. We discuss pre-trained transformers as autoregressive writing styles, connect Deep Learning, automatic writing and choreography. As the departure for our proposed technological ‘détournement’ we use the contextual setting of a philosophy reading and explore how we can feel rather than understand the text. The concept of Dérive, deliberated from Debord’s notion and interpreted into Alice Becker-Hos playful interpretation, is approached through philosophy of technology, artistic research and neuroscience. What happens to the notion of activistic play when technology is choreographing, writing and analyzing our moves in the game? Equipped with a brain- computer-interface, we invite online audiences in a LIVE ONLINE writing session. Focusing on technology bias we approach reading as a performative act situating the philosophical content in practice and approaching audiences as an oracle-intelligence. In this way the setting, the game-mechanics and the audience activities acknowledge the session itself as an assemblage, subversively performing (doing), underlining and showing without telling what is at stake. Here we build on the artistic research project Neuromatic Game Arts/ art games: critical play with neurointerfaces (https://neuromatic.uni-ak.ac.at). At the end of the game loop, a second new text is generated. The words and concepts of the attendees have been algorithmically fed into a Generative Pretrained Transformer in order to generate endless versions of it.. ….. into the loop! The artistic research question concerns the generation of ethical and political questions concerning the measurement of the self.

[…] being driven by an AI system – can be experienced as a flow, rather than a succession of distinct moments. Seen from a traditional modern view, these different concepts of time clash: there is a gap between the technology and the life-world, between objective and subjective knowledge. However, with process philosophy, we can radically question the metaphysical basis for such a gap, and see AI, and how we relate to AI and experience AI, as a process rather than an object, and more specifically a process that fuses “objective” and “subjective” elements, science and lifeworld, scientific time and lived time.

(Mark Coeckelbergh 2021, 3–4)

Part 1 Introduction

In the walkable performance installation Brain Machine Dérive, performed at Angewandte Festival, Vienna 2021, we were curious how the audience/visitors could be invited to the philosophical terrain of the Neuromatic Game Art artistic research project. The starting point for the choreographic direction, introduced by Charlotta Ruth, entailed the idea of a philosophy reading combined with the modality of the Dérive, a recurring and expanded element in the artistic practice of Margarete Jahrmann, Principal Investigator of the Neuromatic Game Art Research Project and professor in experimental game cultures at University of applied Arts Vienna. Inspired by practicing what we philosophically research, we in one of the installations for Brain Machine Dérive outsourced part of the “thinking” to an AI, a GPT-2[1], a generative pretrained transformer. Through the material the GPT-2 was trained on – we, as a research team, created a biased artistic research AI. At the end of this paper we will discuss the creative pros and cons, focusing on artistic writing, as well as ethical implications of this experiment for artistic research.

- [1] In the frame of Carpa 7, Elastic Writing in Artistic Research, The GPT-2 installation was presented in the strand of techno-writing under the name Brain Dérive & Detournement. A neuro- philosophical situated GPT-2 writing game.

The aim of the FWF/PEEK funded artistic research project Neuromatic Game Art: Critical Play with neuro interfaces, AR 581[2] is to create a new form of experimental game art – the neuromatic one. Framed by the discourse on neurosciences and optimisation, the project raises awareness about cognitive conditions, ethical questions about biometric possibilities and the limitations of technologies. Brain Machine Dérive, was conceptualized together with the philosophy strand of Neuromatic Game Art under the guidance of Mark Coeckelbergh, professor in philosophy of technology at the University of Vienna. The development of Brain Machine Dérive took place during regular lab meetings where the research group, consisting of technically literate and conceptually focused scientists and artists, engaged in practice-based interdisciplinary exchange and discourse. Starting with the team constellation, an ambition of the Neuromatic Game Art research group is to make game-design and choreographic analyses part of the specialized discourse relating to wearables, machine intelligence and technological developments[3]. For a more in depth description of our playful and activistic misusage of brain devices, please visit our research Blog[4].

- [2]https://neuromatic.uni-ak.ac.at

- [3] In the interdisciplinary exchange this book among others was used for discussion: Coeckelbergh, M. 2019. Moved by Machines: Performance Metaphors and Philosophy of Technology. Routledge Studies in Contemporary Philosophy, New York: Routledge.

- [4]https://neuromatic.uni-ak.ac.at/blog/ For more insight in previous work with AI see: NEUROMATIC GAN PORTRAIT GAME: THE ARTIST IS MEASURED presented at Parallel Vienna art fair, September 2020.

Ludicism as a method for game-based design sheds light on the human condition. It allows dynamic change, free play with art, science, and game rules. A new conceptual ludic art explores rules of play, systems of investigation and knowledge acquisition through an open-ended game mechanic in the design process. The fundamentals of perception, experience and cognition are considered.[5]

Margarete Jahrmann

- [5] Jahrmann, M. 2021. Neuromatic-Lab Days, 3. September 2021, citation originally used for statement at Researchweek, ZFF University of Applied Arts Vienna.

As the title of his paper “Time Machines: Artificial Intelligence, Process and Narrative” indicates, Coeckelbergh proposes that interaction with technology can be understood as a process of time and narrative. Further he proposes an approach to AI in the line of process philosophy (Bergson, Whitehead, Deleuze, Simondon, Latour). What became especially relevant for the conceptualization of the Brain Machine Dérive environment is how process philosophy goes beyond the subject-object divide and looks at technology from the perspective of becoming (Whitehead) and time as we experience it, durée (Bergson).

Through practice of game-design and choreographic asking, we experimented with rendering usually abstract relations between human and technology into graspable relations, such as; What does it do to our actions and understanding of being when technology is choreographing (scripting), gamifying, and analyzing – our moves? Without drawing a linear conclusion towards this question, Brain Machine Dérive invited the visitors to drift in their own relationship towards these technological developments. In the next part of this paper we walk you through the four positions of the performance installation. This walk-through provides a contextual backdrop for discussing the GPT-2 experiment deeper.

Part 2 The walkable performance installation

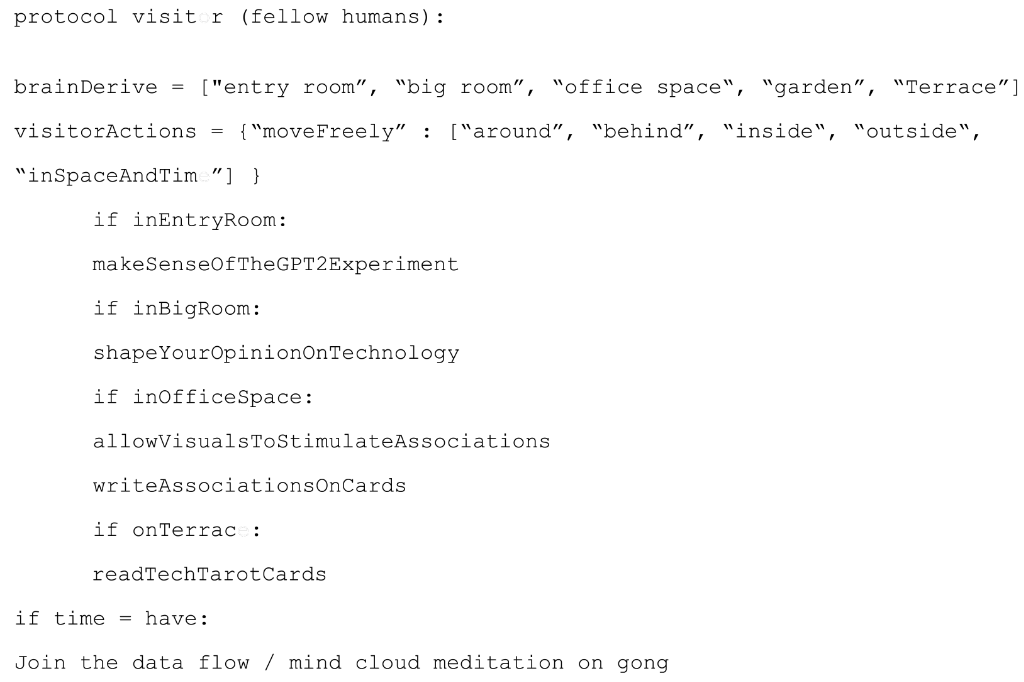

When arriving at Brain Machine Dérive, the sonification of neuroscientific data, developed and played live by Thomas Wagensommerer, intricately inhabited the space. A score written in the style of the programming language python was handed out to the visitors:

Entry Room

In the entry room a Generative Pretrained Transformer 2, a GPT2 (an autoregressive language model that uses deep learning to produce human-like text) moderated the conversation between two philosophers.

Anna Dobrosovestnova had the role of a “philosophy-bot” reading, repeating and playing with the material that was fed to her from her laptop. Coeckelbergh had the task to insist on questioning the content. As the GPT-2 had been trained on philosophy of technology texts relevant for our research as well as texts previously written within the Neuromatic Game Art Research Project a feedback loop of content was generated.

An important part of the GPT-installation was the backend/backside, where Luif, who also trained the GPT2, operated as a human multitasking server – including serving water in the breaks to visitors and performer-facilitators. He picked up the questions posed by Coeckelbergh, rephrased them into a short text-paragraph and typed them into the interface. While the GPT-2 computed the 6 alternative outcomes, the internet was “crawled” for images with the matching keywords. When the GPT2 was ready the results were output on the interface. Luif, the human server, then rolled a dice to choose which of the results would be fed back to the philosophy bot – Dobrosovestnova’s laptop. Upon completion, the sound by Wagensommerer, indicated –new round! To see this, please visit: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1407741/1422985

An observation we’ve artistically researched within the Neuromatic Game Art research project is the human bias in how technology is conceived and how this bias then is automatically built into the technology. The way Luif controlled the installation – from a semi-hidden position, still visible for the visitors – should be noted in the line of this observation. One other example is the live Friday Broadcast series, where Jahrmann together with Wagensommerer and Stefan Glasauer, professor for Computational neuroscience at BTU Cottbus (international research partner, as indicated in the FWF PEEK Project AR 581), question the aesthetics of data-visualisation, exploring how brain-data visualisation and sonification can be used as self-expression or even painting instead of following the traditionally established aesthetics of how brain waves are “expressed”. To see the visuals used in Brain Machine Dérive, please visit: https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1407741/1422979

Office & Terrace

In the office the visitors were invited to look at brain data visuals and engage with a writing task. “Look intensely at the brain-wave stream for 1 minute and write anything that comes into your brain onto these cards.” When the visitors finished looking at the visualisation, Jahrmann invited them to the terrace for a brain-machine Tarot game conversation.

Neurointerfaces, currently at the wake of becoming consumer articles (for example, as EEG headsets), provide direct access to brain activity. However, the devices also breach into the privacy of our thoughts, recording, and measuring very personal data of brain activity, thus bringing up major ethical issues, which strongly influence the research project. Inside Brain Machine Dérive we used “Mind-Reading” as a play-ful interpretation of this intrusion into the brain. Based on each visitor’s imaginations, ideas and sometimes fears towards technology, Jahrmann, who grew up in a family of fortune tellers in the eastern parts of Austria, applied her autodidact training as a “medium” to look into the future.

Big room

In the big room Ruth performed a choreographed speech about the effects of merging human and machine intelligence. The speech was delivered through amplified voice, movement and the sonified neuroscientific data of Wagensommerer.

Dear fellow humans, It’s well known that meditating leads the way inwards but how can we also go forward by going inside? “We need to go inside the brain, inside the skull. […] Between 0.2 and 0.6 seconds before the brain “gives” an order to push the brake pedal, the brain “prepares” the movement. So what if the brain instructed the car to brake directly instead of losing time on instructing the foot? This 0.4 seconds at 100 km / h equals 27 metres. You know what saved metres mean on the road, right?[6]

- [6] Excerpt from pro-technology looped speech, written by Anna Dobrosovestnova and Charlotta Ruth.

When conceiving this speech, we made an effort to take a pro-technology position in the text and Ruth also remained very neutral in how the text was vocalized and delivered.The choreographic movement material (gestures) were simultaneously trained to deliberately mismatch spoken content as if coming too early or too late or too big. Wagensommerer also allowed Ruth’s live voice to travel between different speakers in the room and at points the live voice was replaced by a recorded double. Through asynchronous relations between the human body and verbal expression as well as breaking the logics of speaking text into a device (microphone) and receiving it in real time, we explored how to create a subtext for questioning what was being articulated. The exploration can also be described as how choreographic composition and thinking in relation to technology as a process (as a relationship in time and place), can convey the feeling of what in a philosophical text remains rather abstract.

The data flow – mind cloud Meditation

At a given point the sound of a gong interrupted the activities in all rooms. Visitors and performer-facilitators were invited to gather in the grass outside. In the meantime the words from the cards that people had written when looking at the visuals in the office had been copied into a meditation text written in the style of a cloze.For those who wanted, the meditation gave a short opportunity to place oneself at the centre of the experience rather than being the onlooker. However, the attentive visitor/listener would also notice that the lines of the meditation contained words that were slightly out of context or even quirky. Eventually a word the visitor themselves had written would pop up. Through repeating and integrating the visitors into the narrative of the meditation, our aim was to not only play but potentially mirror experiences back.

GPT-2 Technical Description

For the Brain Machine Dérive installation we used the “Generative Pre-Trained Transformers 2” language model, “GPT-2”, released in 2019. It is known for generating or continuing texts that appear to be written by a human hand. According to a test at the US University Cornell, participants rated the “believability” of the results of the “GPT-2 XL” model with 6.9 out of 10 points (Kreps & McCain 2019). The code architecture is similar to existing language models, but the GPT-2 was trained with the gigantic dataset “WebText” – 40GB of pure text. Our own fine-tuning of the GPT-2 model, on a collection of texts from the Neuromatic Game Art research group as well as techno philosophical texts took several hours of pure computation time.

PART 3 AI & Artistic Writing

When developing Brain Machine Dérive we were inspired by code poetry and instruction-based art. The GPT-2 experiment can also be seen as a contemporary tool in the line of constrained writing and chance-operations introduced from the 1960s and onwards, e.g. Oulipo, Burroughs Cut-Up Method. Artists increasingly use algorithmic input in their creative process. In his keynote at Carpa7, Tim Etchells gave the example of a composer colleague who had written a program that randomly fetched compositions from his own archive that he then would listen to as input into whatever he was currently busy with. In this example the code operates like a time-machine confronting the composer with his past.

Websites and other virtual entities respond to us in real time, they feel live to us even though the only live part is our own activation.

(Philip Auslander 2011)

Based on our experiments, the interaction or possible collaboration with AI inside the medium of writing moves beyond what Auslander ten years ago described as “digital liveness”. It is true that one’s own activation is key also to the situation when collaborating with AI, but for writing it has a deeper potential than the uncanny-valley feeling usually arising when, for instance, communicating with an algorithmic chat-bot. The feeling, not surprisingly, is similar to posing a question to an oracle and with curiosity waiting for the answer. When Neuromatic Game Art research project was represented at the HCI21, 23rd international conference on human-computer interaction, Washington DC / Online, July 2021, Dobrosovestnova, spoke about her experience of performing inside the installation: “The resulting conversation created uncanny but also comical situations where the boundaries between machine and human, meaningful and meaningless control and control were blurred”.

The humor described above was carved out through training the GPT-2 also on more quotidian types of texts – a Neuromatic Game Art blog post announcing a game release is for instance grammatically seamlessly merged with political theories and language style from philosopher of technology Andrew Feenberg. Upon fusion, these materials are combined in time, hierarchy and context. Contributing to the discourse on biased AI, Coeckelbergh points out that we need to attend to the fact that the AI always reproduces and classifies the already existing when reshuffling and reconnecting materials.

…via classification, prediction, and recommendation, AI links past, present, and future in particular ways, which has normatively significant consequences.

(Coeckelbergh 2021, 2)

The curious, but also potentially dangerous thing is that the text-development with AI can absolutely not be dismissed as nonsense. In August 2021 the Neuromatic Game Art research group was granted access to the GPT-3 model. This model is currently only usable in a closed beta version. According to OpenAI, this is necessary to prevent improper use (spam, generation of false information,..). Early in the process, when we hadn’t yet trained the GPT-2 on the relevant papers, it produced rather realistic scientific, often boring text with, for our research, unnecessary facts. This first version of the GPT-2 didn’t work at all for the purpose of the installation. The texts didn’t bring enough friction to the conversation – neither in content or in grammar. Not surprisingly the authors of the original GPT-2 (OpenAI) had not considered training the GPT-2 on artistic research texts and those of us in the research project that don’t have the developer knowhow had simply underestimated how “fluent” AI-writing by now in 2021 is.

Acknowledging this, we thought more conceptually about which texts to train the GPT-2 on. As mentioned, to produce results that created more a sense of surprise or potential valuable input for Neuromatic Game Art, we trained it also on our own texts. To read the results of “our” GPT-2 has now strange history writing or fortune telling effects as if it suggests what art projects we could develop next – but expressed as if it’s already happening. The exposure of six different results, another playful element that we added, makes the controlled randomness (controlled because we knew what texts the GPT-2 was trained on) more visible – as if every beginning sentence is the door to six possible ways of continuing a thought. “Our” GPT-2 is hence far away from functioning through dialectic exchange with the aim of consensus. But if we engage with it as a dialogic tool we can instead use the AI to see possible relations that we haven’t yet recognised in the texts we trained it on. As a process tool, or even an interdisciplinary dialogic research partner we hence recognise a positive potential also beyond the installation.

When writing this text AI proved to be helpful from the very beginning. The soft-ware of the interactive document that we collaborated on is using artificial intelligence for its autocorrect function. The more we, and society at large, are collaborating with AI in everyday situations the more invisible it tends to become. Still, it feels as if there is a big leap between artificial help in regards to form and grammar and artificial help in relation to generating content. Working inside an interdisciplinary artistic research project it becomes graspable how the different ways of approaching a topic are individually rooted in the thinking trained through engaging with each respective media, in our case: game-design, neuroscience, philosophy, sound-art, and choreography. What seems as an intuitive choice for an outsider or even for ourselves in the moment of creation, is often rather a thinking through the specific expression and media that has been trained and practiced. Borrowing this interdisciplinary situatedness, it becomes graspable how everyday practice of thinking with and through technology, changes our way of relating to the world. It also becomes clear how the tech-industry, if being disconnected from other thinking and ways of relating to the world, risks developing unethical, biased and too unreflected devices.

The cultural significance of the interfaces goes beyond its technological function. Interfaces have cultural significance that are decisive in the way we relate to each other and transform ourselves and the way we think.

(Marco Munoz 2013, 50)

We originally conceived the GPT2 experiment due to the curiosity to do – not only speak about, what philosophically motivates us in the research project. Like in the pro-technology speech in Brain Machine Dérive we could ask why we shouldn’t merge with technology when this supports us. As long as a team of persons are engaged and aware of how the AI is trained, it could be valuable for interdisciplinary projects to use AI to predict possible connections and map the “inbetweenness” of the knowledge onboard in a research project.

References

Auslander, P. 2011. Digital liveness: about digital liveness in historical, philosophical perspective. Talk at Transmediale Berlin. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/20473967

Coeckelbergh, M. 2019. Moved by Machines: Performance Metaphors and Philosophy of Technology. Routledge Studies in Contemporary Philosophy. New York: Routledge.

Coeckelbergh, M. 2021. Time Machines: Artificial Intelligence, Process, and Narrative. Philosophy & Technology 34 (2021): 1623–1628. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s13347–021-00479-y.pdf.

Kreps, S., & McCain, M. 2019. “Not your father’s bots.” Foreign Affairs (August 2, 2019), https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2019-08-02/not-your-fathers-bots.

Munoz, Marco. 2013. “Infrafaces – Essays on the Artistic Interaction.” PhD diss. University of Gothenburg.

OpenAI. 2020, September 2. OpenAI charter. OpenAI. Retrieved from https://openai.com/charter/.

Contributors

Charlotta Ruth

Charlotta Ruth (S/A) plays with time and perception inside choreography, participatory art and arts based research. The last years her main topic of investigation has been performative aspects of communication, questioning forms of societal participation and what happens to “liveness” in our updated environment of interfaced reality. Ruth is approaching artistic research with a media independent but site and context-specific approach ranging between stage, gallery, public space, institutional in-between spaces and online.

Margarete Jahrmann

Margarete Jahrmann, is an artist, researcher and game designer. She is Univ.-Prof. in the artistic research PhD program of the University of Applied Arts Vienna and leads since 2020 the Austrian Science Fund FWF research project Neuromatic Game Art: Critical Play with Neurointerfaces. As professor Game Design at Zurich University of Arts she developed a focus on Game Art and Neuro- Epistemology. exhibitions: CIVA Contemporary Immersive Arts 2021, Parallel Vienna 2020, Amaze Playful media 2018.

Georg Luif

Georg Luif is a game developer and researcher, who lives and works in Vienna., Austria. Completed studies in Digital Arts at the University of Applied Arts Vienna and Interactive Media/Games at the University of Southern California. Artistically researches the convergences of art, games and technology.