Unspeakable dialogues:writ in rocks

The full paper takes the form of a presentation/performance via an online conferencing platform lasting 30 minutes, including 10 minutes audience feedback. Positioning the locus of writing beyond the human, it questions our anthropocentrism by drawing on the notion that traces of worlds in motion create recognisable details (forms of writing) that can be read if we pay them the appropriate care and attention. Such issues are essential in our greater literacy for ecological thinking, and actions capable of engendering life-promoting practices. How we may read the writing of the more- than- human realm is not just essential for our own understanding but a communications issue in search of a better relating to a changing reality. Raising questions about the recognition of the “other,” the attention paid to atypical subjects and an ethics of care for those we do not easily understand, are subjects for broader discussion with respect to artistic research in assessing and deciding what kind of writing works and is valuable in artistic research undertakings. Writing is thus conceived as an ethical undertaking rather than a purely formal concern. Our chosen forms of writing direct questions to the critical objectives of artistic research that is ecologically focussed, de- centring the human subject, and inviting new engagements through writing that can be presented in artistic research contexts and publications.

The following is the script to the video that was presented at the CARPA 7 conference. The video can be viewed on the Research Catalogue website.

Part I

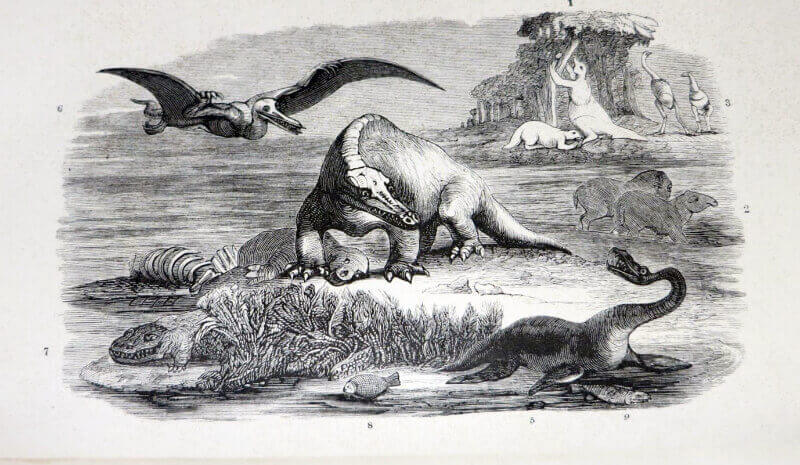

RA: Here are shells that soft bodied creatures have left behind. People call them rocks.

RH: And this soft ooze that doesn’t stay still, what is that exactly?

RA: It’s us.

RH: Us?

RA: Life and minerals co-evolved in deep time by means of a dialogue between geosphere and biosphere. This made, eventually, life, including humans.

RH: So, we are the outcome of unspeakable dialogues?

RA: Mineral surfaces concentrate particular molecules, helping them form longer structures like cell membranes and polymers. These molecules simply cannot write themselves into the ocean or atmosphere – such media are far too dilute, too random. But on surfaces like minerals that provide both the energy and organising topology for molecules to come together, a writing platform is made possible, and, with it, a form of writing that inscribes key steps in life’s origin.

RH: So a writing platform requires a medium that is neither too dilute nor random, but provides surfaces that provide the energy and organising topology for molecules to come together. This is a start for trying to understand what our friends here are calling “elastic writing”.

Part II

Learning and socialising perceptions through repetition over a lifetime, creatures with complex neural systems recognise patterns, generate memories, and start to make shortcuts in processing the world through their understanding, associations, and conditioned behaviours. With the development of memory fields, events are primed by abstractions rather than deriving the state of the world from its immediacy a priori. In doing so, the range of experience becomes narrowed and selective, not only about what is paid attention to, but also how these experiences are valued. The origin of all experimentation resides here, being equated with immersion in various environments and repeatedly engaging with them. In preparation for a more than human notion of knowledge, empathy and different kinds of sensibilities are needed, which do not privilege human concerns above all others.

Part III

Extract from “It” (short story by RH)

One morning, as it awoke from buzzing dreams, it found itself ascending at a dizzying rate. It lay on its back, and if it lifted its head a little it could feel the air rushing past as it was hauled up and away, high into and then beyond earth’s atmosphere. Its bedding slid away and its many legs, pitifully thin, waved about helplessly as it looked at the retreating surface of the planet below.

Above was a huge, white balloon, its thin, bulging polythene membrane pumped tight with helium.

Rising above the dirt and particles suspended in the lower atmosphere, it gazed blankly at the passing clouds. Drops of rain sped by. It felt a slight itch on its belly, raised itself slowly up on its back towards the headboard so that it could tilt its head. It saw that it was covered with a spatter of tiny white spots. When it tried to feel the place with one of its legs, it drew it back quickly, overcome by an icy shudder. It was way below freezing and hairy ice crystals were appearing.

It needed to get the lower part of its body out of bed, but it tried to get the top out first. It lay there, its breath escaping from its chest as if total stillness might bring back some sort of peace and order. The sky sped by and the air became colder still. Brown fluid escaped from its clattering mouthparts, flowed over the edge of the basket and dripped, down towards the earth below. (Hughes 2016)

Part IV

There are rocks that contain life grown inside their cavities. These are living creatures, able to move and exert influence. Their structure is subject to change. They can breathe, with each “breath” lasting from three days to two weeks, and they have “heartbeats” that last about 72 hours. They grow old, obviously. They have names – “trovants”, “stromatolites” and “thrombolites” – describing the chemistry, physics and biology that empower them.

You must stay with my stories if you want to share my adventures.

Part V

The Russian poet Osip Mandelstam wrote that a stone is “an impressionistic diary of weather, accumulated by millions of years of disasters, but it is not only the past, it is also the future: there is periodicity in it. It is Aladdin’s lamp penetrating into the geological murk of future times” (Mandelstam 1979). Others contemplate a stone and conclude it is what it is. The pebble in Zbigniew Herbert’s poem “Pebble” (1968), for example, is described as “a perfect creature” – “equal to itself/mindful of its limits” and possessed of a scent “that does not remind one of anything/ does not frighten anything away does not arouse desire”. It is “just and full of dignity”. The poet nonetheless experiences “heavy remorse” when holding the pebble in his hand, knowing that “its noble body/is permeated by false warmth”. The pebble would appear to resist the poet’s impulse to appropriate and transform it into poetry – it remains a simple pebble and yet, simultaneously, it has become a poem (a poem about its apparent imperviousness to the poet’s desire). Human and inanimate are thereby linked through paradox (the form that celebrates impossibilities of coexistence). The poem’s conclusion would seem to suggest the pebble’s triumph:

– Pebbles cannot be tamed

(Herbert 1986)

to the end they will look at us

with an eye calm and very clear.

And yet the poet’s gaze is now returned – the quality of care and attention has seemingly animated the pebble’s “ardour and coldness” and drawn forth, even in the moment of disavowing such a possibility, its “pebbly meaning” which thus enters the realm of poetic meaning while remaining “pebbly” i.e. outside (human) language.

Part VI

And so we started observing stones not merely as geological artefacts, but as agents engaged in a form of choreography – at a pace barely perceptible to our human senses.

One cannot collide together such disparities in energy and not expect consequences.

It was rumoured that you had decided to sink your face in the landscape, to surrender to soils’ gnawing computations.

Missing you more than my own blood, I returned to look for you. The landscape gazed mutely back, radiating rivulets, inscribing geological, biological and chemical contours – knitting an elemental skin across the indifferent mask of time.

Part VII

Three decades later, another Polish poet, Wisława Szymborska, is addressing another stone. “Conversation with a Stone” (Szymborska 1998) chronicles a repeated request by poet to stone to “enter your insides/ have a look round,/ breathe my fill of you.” The request is repeatedly refused in turn by the stone – neither curiosity, imagined palaces nor bathetic appeals to the poet’s mortality grind down the stone’s resolve, that replies “I’m shut tight./Even if you break me to pieces,/we’ll all still be closed./You can grind us to sand,/we still won’t let you in.”

In the final stanza the stone refuses poetic conceit altogether, bringing thereby the poem to an abrupt end (unlike Herbert’s earlier “Pebble” no accommodation is reached – poet and stone remain implacably ‘alien’ each to the other):

I knock at the stone’s front door.

“It’s only me, let me come in.”

“I don’t have a door,” says the stone.

Against this abrupt slamming of a non-existing door, one could argue that language itself stands in as a type of threshold – after all, that poet and stone are able to communicate necessitates a portal or interface that allows an exchange of perspectives, desire, refusals, accommodations. We can call this poetry. We can call it a philosophical dialogue.

I prefer to call it an unspeakable dialogue, as it involves a dialogue partner operating, seemingly impossibly, outside human language.

Part VIII

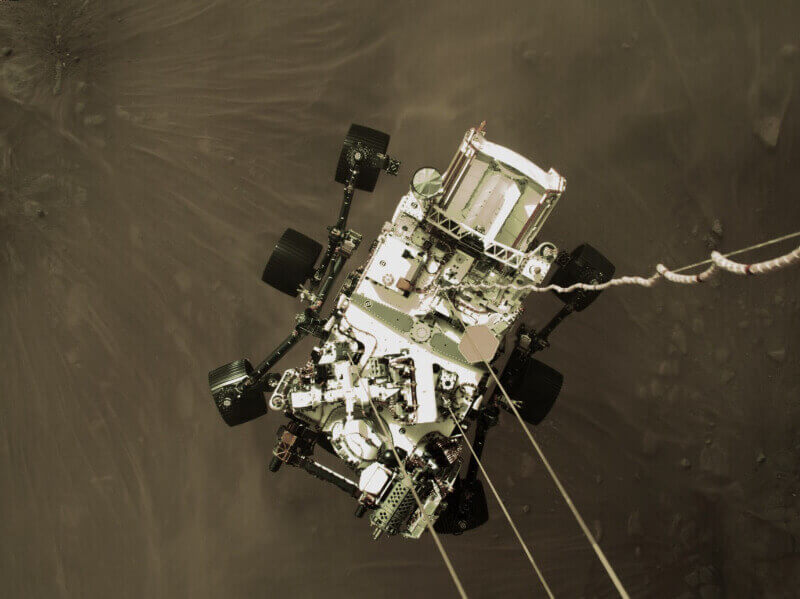

- Mission Name: Mars 2020

- Rover Name: Perseverance

- Main Job: Seek signs of ancient life and collect samples of rock and regolith (broken rock and soil) for possible return to Earth.

- Launch: July 30, 2020

- Landing: Feb. 18, 2021

- Landing Site: Jezero Crater, Mars

- Tech Demo: The Mars Helicopter is a technology demonstration, hitching a ride on the Perseverance rover.

On 21 February 2021, the Perseverance rover successfully landed on the surface of Mars. Looking for signs of life its specific mission is to sample the Martian soils, performing the work of an instrument that in space and time, may help us “read” the Martian rocks.

What do Mars’ rocks have to tell us? How might they “speak”? Why should they acknowledge us?

Part IX

All know what is meant by the Book of Nature. But nature is rather like a library than a book; for it is the general and well-stored receptacle of all that has ever been created, of all we know and all we have not yet learned, of all that is animate and all that is inanimate, of all that is happening and all that has happened, not only on the earth, but above the earth, and within it and around it. Nothing once existing has entirely disappeared. Everything has been photographed and is preserved for use and reference somewhere and somehow. Every year something is discovered that was not before known; but there remains so vast an amount of material yet unknown and unrecorded, that we may be quite sure it will never be exhausted, however long the human race may remain on earth, or however highly the faculties of man may be developed.

(Ansted 1863)

In the riverbed and sea-beach, in the sun, wind, rain and frost, Mr. Ansted finds the key to the language of the great stone book of the world; he then opens its leaves and shows us the stones of the great stone book. Then he points out the placements and displacements of the stones of the great book, in the brick-pit and gravel-pit, in the quarry, the mine, by volcanoes and earthquakes and other disturbances of rocks. Next the treasures, – gems rich and rare, metals precious – the more really precious the more useful. And so through his brief narration of the world’s own special wonders, we are brought to the end of his pretty little book that prettily tells the great story of the Great Stone Book.

Part X

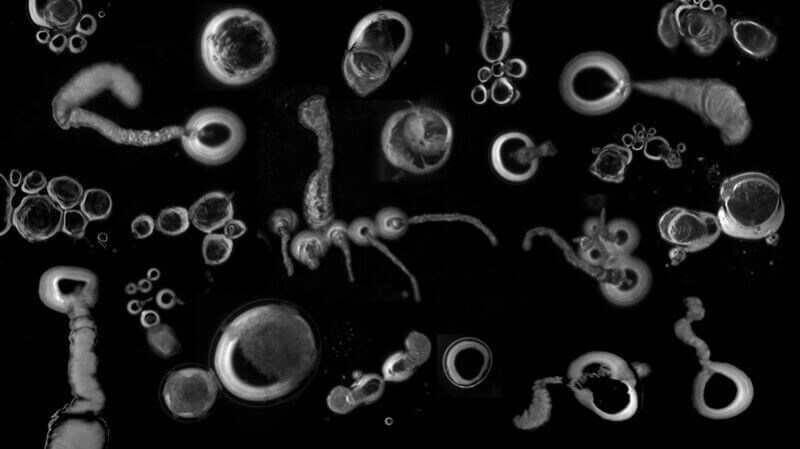

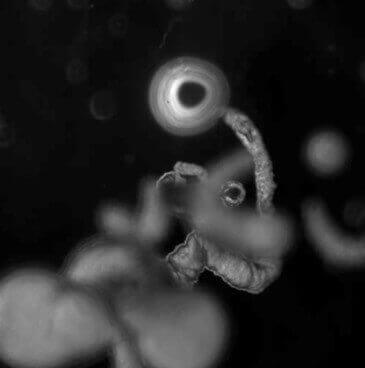

In 1892, Otto Bütschli, a Swiss zoologist, added a few drops of concentrated alkali to a field of olive oil in a glass dish. As the main droplet body broke down he could just, unaided, see the daughter droplets squirming around the dish, bumping into each other and passing around each other in a remarkably lifelike manner.

“I’ve seen these somewhere before,” observed Bütschli, “these are amoebae, unicellular creatures. Now I have proven that biology is only a more complex expression of chemistry!”

Part XI

While resisting the tendency to speak for nonhumans, rather than along with them, it is possible to expand our feeling together with those that are different from us. If we are to speak to “others” no matter how unlikely their agency may seem, no matter how “alien” their nature, then we must be prepared for them to climb into our skin, and we into theirs and walk around in it awhile. By allowing thought itself to be creatively and experimentally present within our experiences, techniques for receptivity can be acquired for “composing with creative practice, for composing emergent collectives, for composing thought in the multiplicitous act.” (Manning & Massumi 2014)

*

Appendix

Positioning the locus of writing beyond the human, this presentation questions our anthropocentrism by drawing on the notion that traces of worlds in motion create recognisable details (forms of writing) that can be read if we pay them the appropriate care and attention. Such issues are essential in our greater literacy for ecological thinking, and actions capable of engendering life-promoting practices. How we may read the writing of the more-than-human realm is not just essential for our own understanding but a communications issue in search of a better relating to a changing reality. Raising questions about the recognition of the “other,” the attention paid to atypical subjects and an ethics of care for those we do not easily understand, are subjects for broader discussion with respect to artistic research in assessing and deciding what kind of writing works and is valuable in artistic research undertakings. Writing is thus conceived as an ethical undertaking rather than a purely formal concern. Our chosen forms of writing direct questions to the critical objectives of artistic research that is ecologically focussed, de-centring the human subject, and inviting new engagements through writing that can be presented in artistic research contexts and publications.

References

Anonymous. 1863. “The Great Stone Book of Nature. By D. T. Ansted M.A., F.R.S., F.G.S. London and Cambridge: Macmillan and Co. 1863.” The Geologist 6, no. 6 (1863): 240–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359465600001489.

Ansted, D.T. 1863. The Great Stone Book of Nature. London and Cambridge: Macmillan and Co.

Herbert, Z. 1986. Selected Poems. Translated by Czeslaw Milosz and Peter Dale Scott. Ecco Press.

Hughes, R. 2016. “It.” Odyssey: The e-Magazine of the British Interplanetary Society (September 2016). https://www.bis-space.com/membership/odyssey/Odyssey43_September2016.pdf (accessed 14.11.21).

Mandelstam, O. 1979. “Conversation about Dante.” In The Complete Critical Prose and Letters. Edited by Jane Gary Harris. Translated by Jane Gary Harris and Constance Link. Ann Arbor, Michigan.

Manning, E. & Massumi, B. 2014. Thought in the Act: Passages in the Ecology of Experience. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Szymborska, W. 1998. Poems New and Collected: 1957–1997. Translated by Stanislaw Baranczak and Clare Cavanagh. Harcourt Brace.

Contributors

Rolf Hughes

Rolf Hughes is Professor of the Epistemology of Design-Driven Research at KU Leuven and Director of Artistic Research for the Experimental Architecture Group which develops pioneering transdisciplinary research, design prototypes and immersive experiences for the emerging ecological era. A prose poet, he applies artistic and design-led research methods to explore ecological epistemologies that foreground ethical relationships with non-human agencies in architecture, bio-design and beyond.

Rachel Armstrong

Rachel Armstrong is Professor of Experimental Architecture at the School of Architecture, Newcastle University, Visiting Professor at KU Leuven, a Senior TED Fellow and a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Rising Waters II confab Fellow. She holds a First-Class Honours degree with 2 academic prizes from the University of Cambridge (Girton College), a medical degree from the University of Oxford (The Queen’s College) and a PhD (2014) from the University of London (Bartlett School of Architecture).