Writing with trees

This contribution to CARPA 7 consisted of two parts, a pre-conference workshop and a video presentation in a panel. The introductory Power Point presentations to both parts are available online as pdf files (see pdf file) on the RC (Research Catalogue). The workshop took place via zoom on 25 august from 3 to 4 pm and was presented in the program (see program) in the following way:

“Writing to your chosen tree – a workshop”

In this workshop we will explore writing a letter to a tree of our choice next to that very tree and share parts of those letters with each other via zoom. Thus, the participants are asked to choose in advance a tree that is important to them, or to go to a nearby park and approach a tree that seems inviting. Please, be prepared to bring your computer or phone or other device with zoom connection next to the tree at the time of the workshop. And prepare pen and paper in order to be able to write the letter to the tree by hand. Looking forward to meeting you and the trees…

I was sitting in front of the Royal Library in Humlegården Park in Stockholm, under a huge plane tree, with an umbrella. No registration was needed, so I did not know what to expect; however, there were enough participants joining in from various places to make the workshop a meaningful experience. The workshop was based on provocation created for the project Designing a Pluriversity (see provocation) and was structured into a ten-minute introduction, a twenty-minute writing assignment and thirty minutes of sharing and conversation. Despite planning to do so, I did not write a letter to the plane tree but moved indoors from the rain to facilitate the final conversation.

“Writing Letters to Trees with the Trees”

The video paper was included in session 11 in the strand Dis (guised) writing on 27 August from noon to 1.30 pm, (see the program). The abstract (see abstract online) explains the presentation as a form of Dis (guised) writing in the following way:

This presentation is related to the strand in the sense of being an ”experimental form of writing in artistic research”, with the aim to subtly ”disrupt and displace conventions” and ”queer scholarly writing”, related to ”interests in fictioning and speculative fabulation”. The practice of writing letters to trees by the trees, a form of semi-automatic writing addressed to the tree with the camera as witness, has been developed as part of the project Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees and explored with various trees in Finnish, Swedish and English. The presentation will include excerpts of videos depicting writing with trees as well as excerpts from the letters.

This presentation proposes the perhaps controversial idea that a thought occurring to the writer while writing next to the tree might be provided by the tree, as their contribution to the conversation. This idea can be understood as a literary gesture or dismissed as pure fantasy, but it could also be seen as a possible solution to the dilemma of communicating with trees. Patricia Vieira proposes “the notion of inscription as a possible bridge over the abyss separating humans from the plant world [because] all beings inscribe themselves in their environment and in the existence in those who surround them.” (Vieira 2017, 217) Following this line of thought, although we could expect the human who writes to the tree to be doing the inscription, we could also see the trees inscribing themselves onto the text, which emerges in the encounter.

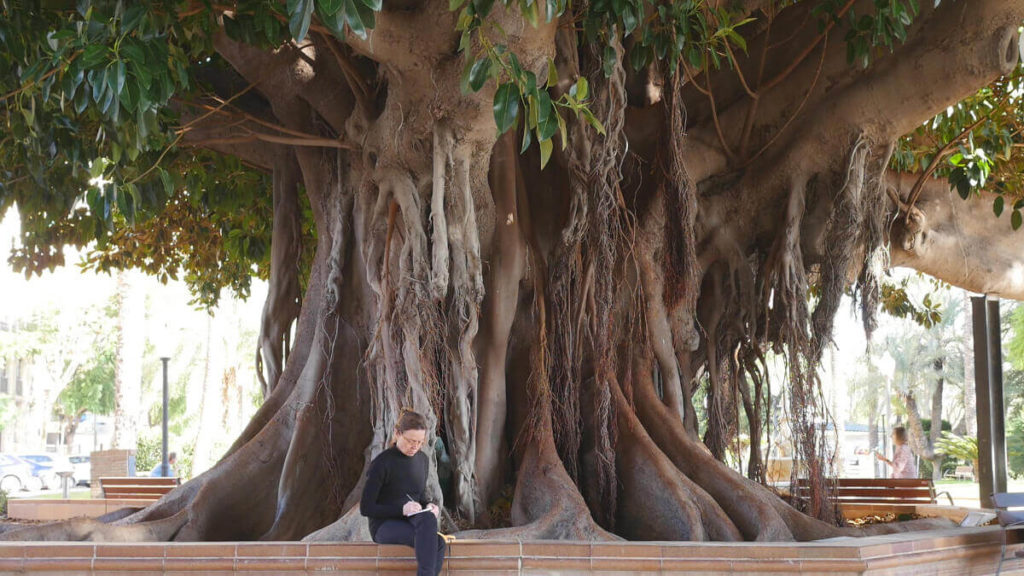

As my presentation I shared a video performed and recorded on Christmas day 2019 with an Australian banyan tree in Alicante, with the original letter and some more recent reflections added as a voice-over narration. The original videos are available online on the RC (see original videos). The video with the narration made for CARPA 7 can be watched on vimeo (see Dear Ficus Macrophylla Carpa 7).

Transcript of the voice-over text

(the links and parenthesis in the transcript are added for the proceedings)

25 December 2019

Dear Ficus Macrophylla, or Australian Banyan Tree. I came back to visit you with a notebook and my camera, because the idea occurred to me this morning, before I was even properly awake. I came here yesterday, as it felt like a duty of sorts. If I am to use your trunk, or the image of your trunk as a logo for my blog (see Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees blog), I should at least thank you for that. And after visiting you here in the park by the harbour, I looked up some facts about you on the internet and I got to know your name, and that you are from Australia originally. And also, that you are sometimes called the strangler tree, because if your seed germinates on the branch of another tree you will grow roots down to the earth from there and then slowly strangle your host. Why that should be necessary I did not really understand, but perhaps it is a question of space. Here in the park, you have plenty of space, each of you, with a ceramic fence surrounding every one of you. It is really funny to think that you are only one tree with all those roots and stems and branches turning into roots hanging down, because you look more like a group of trees. Well, that is what they say most trees actually are, communities of various critters, to use the term Donna Haraway prefers to creatures.

There are lots of people admiring you and probably some of them will be recorded on video as well, but I cannot do anything about it, so why should I mind, at least not now. I only hope that not too many people would stand in front of the camera, and obviously they do not. The dogs are worried, of course. But now I am sitting on the bench-like fence, so my behaviour should not be too disturbing to them. The reason I am sneezing is that the ceramic bench is rather cold, and I hope I will not get seriously ill, well, probably not. – I wonder what brought you here, or rather, who brought you here. The information on the board is in Spanish. There are several of you only in this park, and a few blocks from here there is another small park which is constructed around a few of your kind. It seems that people value the shade you create and also enjoy the strange forms of your roots and trunks. But they do not eat your fruits, I suppose. Birds do; that is how you can travel far and wide. I think there must be some colonial exoticism behind the idea of planting trees like you in the city park. And of course, you are the exotic one here, despite all the palm trees around you. Your form is sculptural and exciting, and there is something slightly scary about you as well. Although sitting here at a safe distance from you, and in the sunny morning, I am not scared. The time needed for you to strangle my body is so long that I guess I could move away in time. And to be honest, you do not look like strangling anybody. I guess it must be only if you happen to grow somewhere where there is not enough space that you would engage in combat of that kind. I think you look like living very happily just where you are, without attacking anybody – unless they attack you, I guess. But then again, there is so much of what you do that I cannot see.

I wonder if you would grow into a new tree from a branch of your root. Could it develop leaves of its own to do some photosynthesis? Probably, why not? But not a very small piece, I guess. I do not want to try. Your leaves look exactly as the classic Ficus trees we have as house plants. I used to have one with exactly the same kind of leaves, but it died a long time ago, how long, I cannot remember. The Ficus plants that I have now at home are not of the same kind, although clearly relatives. – Time to stop writing now, I guess, or time to stop the camera. Perhaps I will return to you later today. Meanwhile, take care!

*

And now, reading and recording this letter written to you one and a half year later, in another city far away from you, I take the opportunity to use the elasticity of writing and the conventions of moving image editing to add some further thoughts. It feels strange, although writing to somebody who is not there next to you is of course a more common way of letter writing.

Writing letters to trees next to the trees has been an important strategy for performing with trees, developed at the very end of the project Performing with Plants (see project archive Performing with Plants), and further experimented with in my current project Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees (see project archive Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees). The act of writing a letter to a tree while sitting next to the tree was something that occurred to me only after using the letter form in a voice-over text written for a video work afterwards. Subsequent experiments were based on this experience of addressing the tree rather than speaking as the tree or on behalf of the tree, as I had done for example in the small audio works “Trees Talk” (see summary of Talking Trees). When experimenting with ways of using text as the sound in the artwork itself I wrote a voice-over text in the form of a letter to the tree I performed with for a year in Stockholm, Year of the Dog in Lill-Jan’s Wood (Sitting in a Pine) (see video Year of the Dog in Lill-Jan’s Wood (Sitting in a Pine) – with text). The letter was my first attempt at addressing the tree and including it as an agent and co-performer, not by speaking on behalf of it but “to” it, in a semi-fictional manner. (The text has also been published separately as “Dearest Pine”, Arlander 2020a).

The first letter to a tree written next to the tree, performing writing for camera, as it were, was made only at the very end of the project. I had the impulse to sit and write together with the first old olive tree I met in Ulldecona on my trip to visit some ancient olive trees in Catalonia at Christmas time in 2019. (See documentation of the first writing experiments in Ulldecona and Alicante). To this first olive tree I addressed several letters; soon I realized, however, that the act of writing letters to the tree was not meaningful from a distance. It was the act of sitting next to the tree that mattered, focusing on the tree and entering into a kind of dialogue with it there and then, albeit via writing. (These letters have also been published in a video essay for JER, Dear Olive Tree).

Actually, this action produces a monologue, rather than a true dialogue, but in the best of cases it can serve as an exercise in focus and observation. In the worst case, however, the act of writing further accentuates the gap between the human and the vegetal mode of existence by bringing in language and writing, which are decidedly human activities, rather than breathing and perceiving, which are much more closely related processes, for both humans and plants. The action of writing in front of the camera, of “performing writing”, brings in an added dimension. My first experiments in Ulldecona consisted only of this action, the video depicted the act of writing like any action. In later experiments I realized I could record the text and add it as a voice-over to the video.

While planning a follow up to the project the next year, I began to deliberately develop some kind of extended pen pal relationship with a pine in Stockholm. I chose a small pine tree on Hundudden as my pen pal to visit every now and then and to sit and write next to, imagining that I could write letters to it from my trips later that spring. I soon realized, however, that writing was only meaningful next to the tree, and planned to return to the tree regularly, which proved impossible due to the pandemic.

Another way of using letter writing, that I explored during my brief stay in Nirox Sculpture Park in South Africa, was writing a letter to the tree while performing for the camera with the tree, and then recording that text and adding it to the soundtrack of the video. The first experiments with this way of working I made with two small firethorn rhus shrubs that I performed with in Nirox, resulting in the video works Dear Firethorn Rhus[1] (see video Dear Firethorn Rhus) and Dear Firethorn Rhus II[2] (see video Dear Firethorne Rhus II) . The letters are published in the ARA or Arts Research Africa publication online. (Arlander 2020b, 86–91. See Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees in Johannesburg with Environs.)

- [1]Dear Firethorn Rhus (2020) 20 min 15 sec was performed in Nirox Sculpture Park 18.3.2020. The text written during the performance was recorded and added as a voice-over to the video Dear Firethorn Rhus (with text) (2020) 6 min.

- [2]Dear Firethorn Rhus II (2020) 20 min 15 sec was performed in the Nirox Nature Reserve 19.3.2020. The text written during the performance was recorded and added as a voice-over to the video Dear Firethorn Rhus II (with text) (2020) 6 min.

The reading of the text is usually much faster than writing it by hand, and thus the spoken text is much shorter than the writing of that same text in the image, which means that the voice-over cannot really be properly synchronized with the writing of those same words. An impression of presence, of here and now, is nevertheless easily created with the combination of showing the act of writing and reading the text aloud. The effect of being able to follow the writing of the person in the image, as if she would speak to herself while writing can be quite strong. This kind of illusion is actually making the video more conventional, in terms of cinematic habits, and gives quite a lot of importance to the text spoken. This depends on how closely one can see the actions of the writer, and how the speaker phrases her sentences. The combination of writing a text and then speaking it as if at the same time is something I have explored further in later experiments.

I have been writing to trees also at home in Helsinki, such as with a pine in Brunnsparken (see documentation of the performances) and a spruce on Harakka Island (see documentation of the performances). In various residencies, including Mustarinda[3] (see videos Dear Spruce, Dear Birch and Dear Deceased) and Öres[4] (see videos Writing with a Pine, Writing in a Pine, Dear Pine, Pines by the Path), Kilpisjärvi (see videos Dearest Mountain Birch and Dear Mountain Birch) and Eckerö (see various experiments with an ash tree), I have further explored this strategy, writing letters to trees in Finnish, Swedish or English, reading and recording the texts aloud and adding them as voice-overs to the videos. In some cases, I have translated the Finnish or Swedish letters to English and added the translation as subtitles, and in some cases used the text only in the form of subtitles, as a visual scroll without sound.[5] (See videos Dearest Pine (with text) and Esteemed Pine Tree). I have also experimented with addressing the tree with speech directly, rather than writing, recording my words with a handheld microphone (see videos Tala om det för Tallen 1–7).[6]

- [3]Dear Spruce (2020) 20 min 15 sec, edited into the variations and Rakas kuusi (2020) 5 min 47 sec, and Rakas Kuusi – Dear Spruce (2020) 5 min 47 sec, was written with a spruce in Mustarinda on 25 September 2020. Dear Birch (2020) 20 min 15 sec, edited into the variation Kära Björk (2020) 5 min 50 sec, was written with a birch in Mustarinda on 29 September 2020. Dear Deceased (2020) 20 min 15 sec, edited into the variations Dear Deceased (with text) 6 min 26 sec, was written with a dead spruce in Mustarinda on 29 September 2020.

- [4]Writing with a Pine I and II (2020) 20 min. was written, twice, with the same pine on Örö, on 10 November 2020, Writing in a Pine (2020) 13 min, edited into Writing in a Pine (with text) (2020) 5 min 20 sec, was written in a pine tree on Örö 16 November 2020, Dear Pine (2020) 10 min, edited into Dear Pine (with text) (2020) 4 min 30 sec, was written with a pine tree on Örö on 18 November 2020, Pines by the Path (2020) 16 min 20 sec edited into Pines by the Path (Kära Tall) (2020) 4 min 5 sec, was written with two pines on Örö 1.12.2020.

- [5]Dearest Pine (with text) (2021) 15 min 45 sec was written in and with a pine on Örö 21.2.2021. Esteemed Pine Tree (2021)16 min 15 sec was written in and with a pine on Örö 23.2.2021.

- [6] The first Tala om det för tallen (Tell it to the Pine) 1 (2021) 8 min 50 sec, was spoken to a pine 11.1.2021. The last one, Tala om det för tallen (Tell it to the Pine) 7 (2021) 12 min 33 sec, was spoken to the same pine on Örö 13.11.2021. (scroll down the RC page to see them all).

The act of writing a letter to a tree next to the tree can be understood as a performance, an action performed for the camera like any action, comparable to listening or looking. It can be used in other ways as well. First of all, it is also an exercise in writing, a practice of semi-automatic writing, writing whatever comes to mind at that moment without censoring it, and thus a manner of producing text. Secondly, it is a therapeutic practice of sorts, expressing one’s thoughts and problems to the tree as if to a teacher or mentor, a way of articulating one’s concerns that can in itself be helpful. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, addressing the tree is a practice of focusing on the tree as a living being, trying to pay one’s respect and in some manner make contact with an entity that this different from us and often overlooked. (This I have discussed, for example, in the online talk “Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees”, 30.3.21, Knowledge in the Arts #2, see recording of the talk).

Because these experiments grew out of attempts at performing with trees, the interesting question for me has been what kind of relationship they create to the addressee, the tree, rather than the question of what kind of writing they produce – which is not always very interesting, I have to admit. Addressing the tree rather than speaking about the tree, or as the tree, or on behalf of the tree, is one option of encountering trees and performing with them. The problem remains, however, whether writing actually emphasizes our difference by making our relationship more fictional compared to simply breathing, performing and appearing together. The use of human language, and writing in particular, seems almost like creating an extra barrier between the human and the plant, rather than focusing on commonalities like breathing and growth.

Rather than speaking for the tree or on behalf of the tree I try to speak to the tree, or with the tree. Rather than writing about trees I try to write next to them, with them in some sense, with you. This poses new problems; am I simply re-inventing an age-old poetic convention, projecting my own thoughts on you and imagining my internal dialogue as a conversation with you? (Ryan 2017) By treating plants as persons, following Matthew Hall’s (2011) idea, rather than acknowledging the vegetal in me, as Michael Marder (2013) suggests, do I neglect our joint participation in zoe, in an expanded understanding of life to use Rosi Braidotti’s (2017) term. Am I disregarding our trans-corporeality, a term Stacy Alaimo (2010) has coined to describe our interconnectedness? Is writing actually emphasizing our difference by making our relationship more fictional compared to simply breathing, performing and appearing together?

In her text “Phytographia: Literature as Plant Writing” Patricia Vieira asks “’Can the Plant Speak?’” And moreover, “Would we be prepared to listen”, she adds, “Or would we rather, as Spivak warned in the case of the subaltern, superimpose our thoughts, reasoning, and preconceived ideas, perhaps even in a well-intentioned manner, onto the plant?” (Vieira 2017, 216–217.) Despite problems with the analogy, “the similarities between the subaltern and the plant are also striking” (Vieira 2017, 217) she notes. “Relegated to the margins of Western thought, both categories have been posited as the negative images of modernity’s triumphant ideals.” (Ibid.) Vieira suggests that “following in the footsteps of postcolonial studies, we make an effort to interpret the stories of plants”, although “this is a challenging endeavour.” (Ibid.) She proposes “the notion of inscription as a possible bridge over the abyss separating humans from the plant world” because “all beings inscribe themselves in their environment and in the existence in those who surround them.” (Ibid.) Although it seems that the human who writes to the trees is doing the inscription, following this line of thought we could also see the trees inscribing themselves onto the thoughts of the human and the text emerging in the encounter. I have actually experienced something along those lines when writing to some trees. In order for that to happen, I have to sit next to the tree, spend time with the tree by the tree. And unfortunately, that is not possible with you now. Thank you anyway for letting me use you as the backdrop for these notes and many greetings from the north! Take care!

Some afterthoughts

I have tried to present the idea of writing letters to trees in the context of critical plant studies and environmental humanities without much success, so far. Looking at the practice in the context of elastic writing, not only as an action to be performed and not only in terms of what this action does to the human-tree-relationship, but also with regard to what it does to the writing, the resulting text, was a refreshing experience. As was indeed participating in a panel with very strong filmic and performative contributions by Rolf Hughes & Rachel Armstrong and by Harri Laakso. They inspired me to question my minimal use of the camera and explore those dimensions further in the future.

References

Alaimo, Stacy. 2010. Bodily Natures. Science, environment, and the material self. Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

Arlander, Annette. 2020a. “Dearest Pine.” In Jack Faber and Anna Shraer (eds.) Eco Noir: A Companion for Precarious Times. Academy of Fine Arts, Uniarts Helsinki Publishing, 105–112. https://taju.uniarts.fi/handle/10024/7185

Arlander, Annette. 2020b. Meetings with Remarkable and Unremarkable Trees in Johannesburg and Environs Arts Research Africa, The Wits School of Arts, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, https://wiredspace.wits.ac.za/handle/10539/30395

Arlander, Annette. 2021. “Dear Olive Tree.” Journal of Embodied Research, 4(2): 5 (19:40). 2021. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/jer.70

Braidotti, Rosi. 2017. “Four Theses on Posthuman Feminism”. In Anthropocene Feminism, edited by Richard Grusin, 21–48. Minneapolis & London: University of Minnesota Press.

Marder, Michael. 2013. Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ryan, John C. 2017. “In the Key of Green – The Silent Voices of Plants in Poetry.” In The Language of Plants – Science, Philosophy, Literature, edited by Monica Gagliano, John C. Ryan and Patricia Vieira, 273–296. Minneapolis London: University of Minnesota Press.

Vieira, Patricia. 2017. “Phytographia: Literature as Plant Writing.” In The Language of Plants – Science, Philosophy, Literature, edited by Monica Gagliano, John C. Ryan and Patricia Vieira, 215–233. Minneapolis London: University of Minnesota Press.

Contributor

Annette Arlander

Annette Arlander, DA, artist, researcher and a pedagogue, one of the pioneers of Finnish performance art and a trailblazer of artistic research. Former professor in performance, art and theory at Stockholm University of the Arts, visiting researcher at Academy of Fine Arts University of the Arts Helsinki. Her research interests include artistic research, performance as research and the environment. Her artwork moves between the traditions of performance art, video art and environmental art.