Montreal, 27 June 2016

Dear Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, dear Ari Benjamin-Meyers,

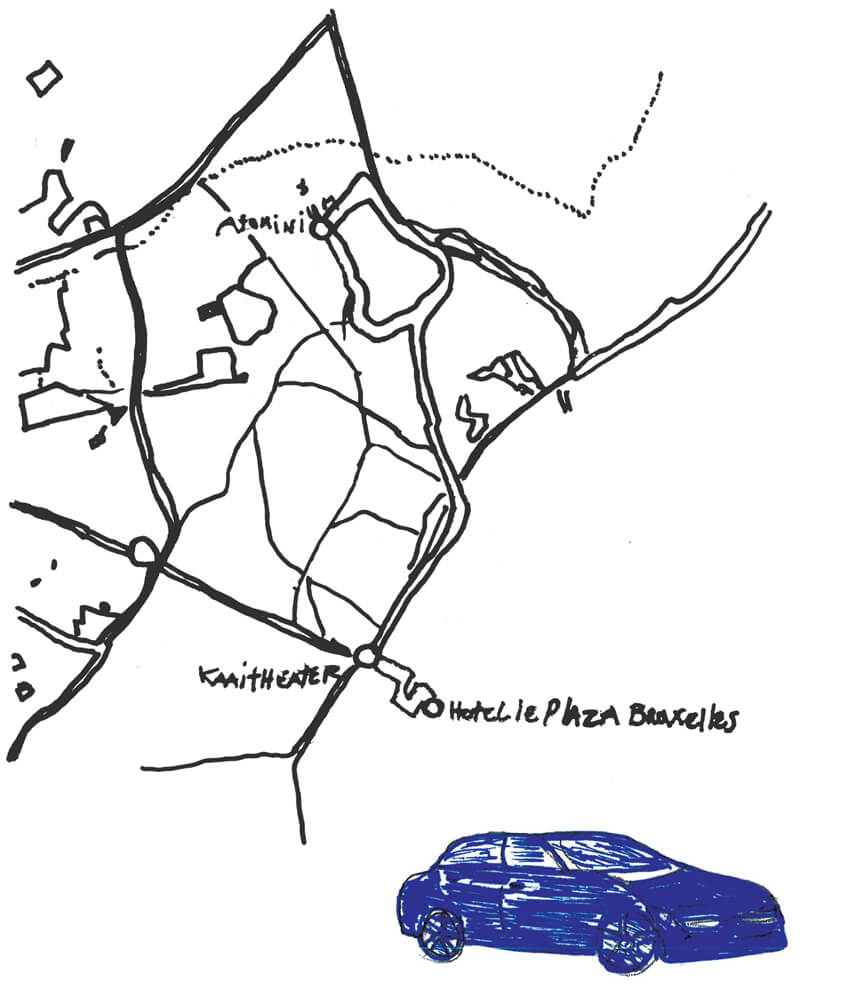

Your project K.85 (2011) will remain in my memory for a long time yet. I was intrigued by the description of your show in the Kaaitheater’s brochure, in Brussels: “a black comedy on ‘missed connections’ inspired by Martin Scorsese’s After Hours (1985).”

K.85 was presented as one part of a three-part performance including K.62 – a black comedy for audience and orchestra (inspired by the adaptation of Kafka’s The Trial by Orson Welles in 1962) – and K.73 (2011), which draws upon the film Malpertuis (1971) by Harry Kümel with characters trapped in Cassavius’ labyrinth. Since I was only passing through Brussels, I wasn’t able to see the whole trilogy; I opted for K.85. My curiosity was piqued by the note indicating that the performance site would be confirmed by telephone on the day of the show.

Here’s what I remember, and the reflections that emerge from my memories of the show, six years later.

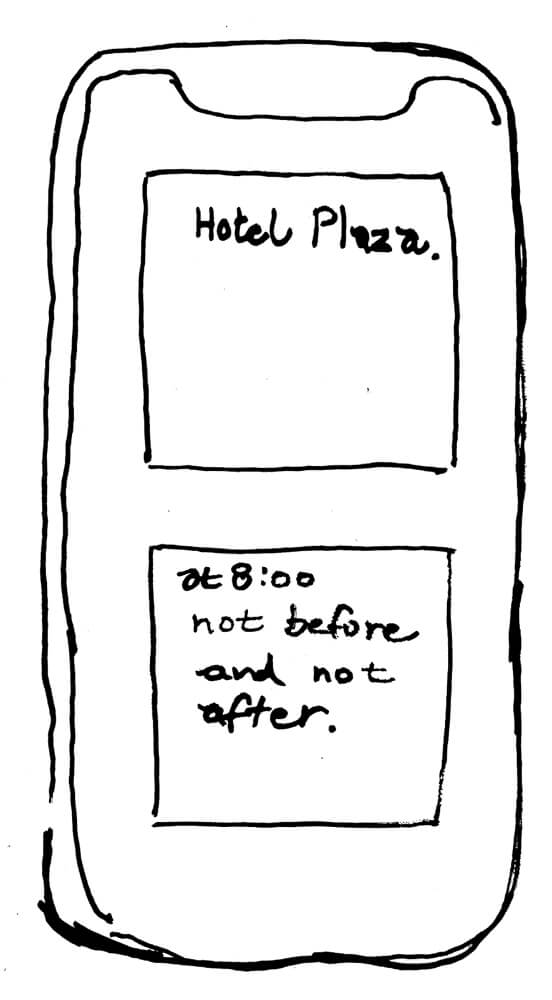

3 March 2011. I receive a text with the instructions for K.85. I’m asked to show up at exactly 8:00 in front of the Hôtel Plaza in Brussels. It says specifically: at 8:00, not before, and not after.

Rectangle

There were many rectangles in K.85: the hotel hall, limousine, restaurant, concert hall, backstage corridors, stage…

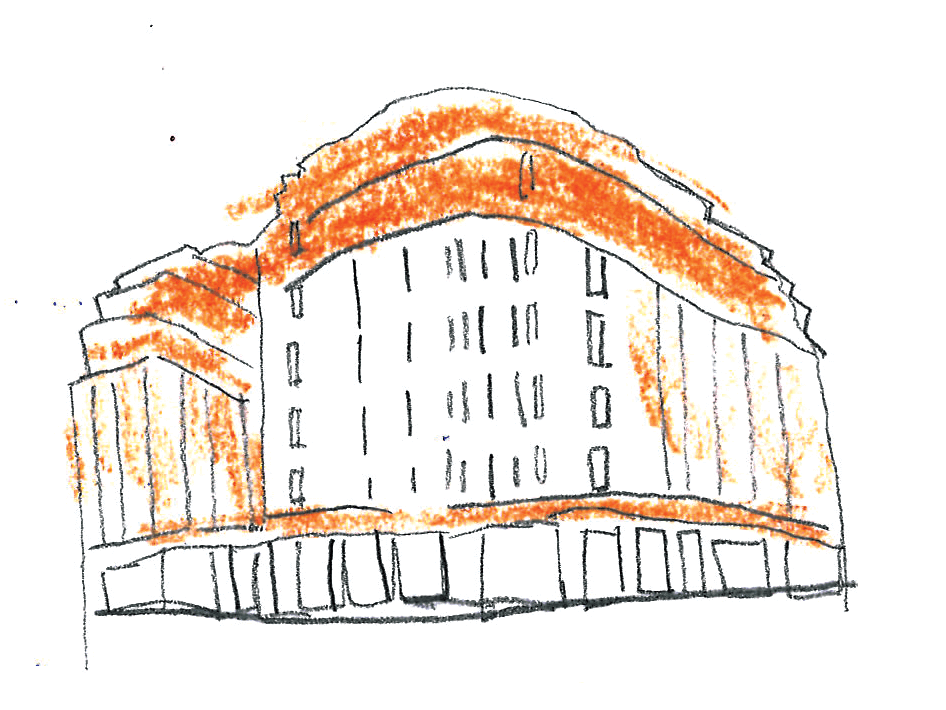

When I arrive, I look around for the crowd, walk once around the building, but there’s no one, and no line-up in sight. I go into the lobby – no one. I ask the concierge where the people are for the festival performance, but he doesn’t seem to know anything about it. Worry starts to gnaw at me – I’m scared I’ll be late. I go back outside. A limousine is now parked in front of the hotel, and the chauffeur steps forward to hand me an envelope.

Chauffeur: This is for you.

I see an envelope with “K.19” written in black marker.

Me: Um, no, I’m here for a performance.

Chauffeur: Take your seat.

And he hands the envelope back to me with a smile.

Me: What’s going on?

Chauffeur: I can’t say anything.

I get into the limousine with the distinct feeling of entering a David Lynch film. The chauffeur puts on a CD with flamenco music and starts the car. We drive slowly, but surely, and now we’re on the outskirts of Brussels, at the edge of a forest. Sweating more and more, I keep asking my chauffeur about the evening, but he invariably replies: “I can’t say anything, but please don’t worry.”

The flamenco music heats up and I can’t decide if I like it or hate it. The chauffeur is now murmuring a few words into a walkie-talkie.

Oh goodness, do I have my passport with me? If I don’t throw myself out of the car, I’ll throw it out the window into this accursed forest. At least that trace will remain. But why don’t I decide to get out of the car? Where are we?

To bifurcate

A clear moment of bifurcation in K.85 is when I receive an envelope from the driver asking me to follow him in the limousine. The expected performance took a very surprising turn from this shifting moment.

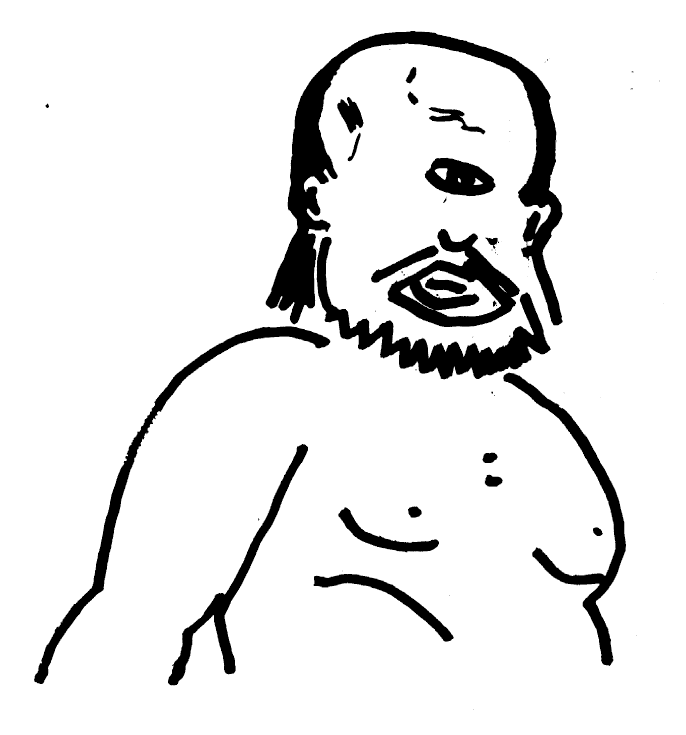

The chauffeur is large and bald, and in spite of his friendliness, he looks like the very archetype of the big strong man. If he had only one eye he could play Polyphemus, the giant cyclops from Homer’s epic. I remember him in the television series The Odyssey (1968) by Franco Rossi, with actress Irene Papas as Penelope.

Through the window, the night and the trees are very dark, and I’m driving along the edge of a maleficent forest with Polyphemus at the wheel, to the sound of wild flamenco. But silence would be worse.

In this endless night, I resolve to be a Penelope who waits. Dominique, Ari, I have to say that at this point in my story, I hate you.

Little by little, the cars we pass along the road calm me down. A rolling object can comfort. My parents used to leave my brother and me at my aunt Rita’s in the summer. Her house was in Lanoraie, beside Highway 138, which stretches along the Saint Lawrence River. Trucks and delivery cars would rumble past day and night. Their engines soothed my brother’s and my own sleep.

Brussels, with my chauffeur.

Maybe I should have opened my window. If we were in a convertible, for example, would I have felt better? In his book Window, art, historian Gerard Wajcman (2004, 95) writes:

Alberti speaks of an elementary gesture one must make before beginning to paint, in order to be able to begin: for me, to begin to paint, I pierce a hole, I open a window—through which I will watch the story unfold.

The objects I glimpsed along the road (lampposts, lines on the ground, cars we passed) and the rhythm of the car eventually slowed me down and brought me into another register of time. Seated inside this limousine that kept on, imperturbable, I began to see. And then I decided to open this window Alberti refers to, and to enter into a story I was going to tell myself.

The borderline between image, film, fiction, and reality became porous and then, somewhere within me, the process of creation of the image and space began.

All at once, inside the car, I became the camera of a film. My chauffeur was a character, the walkie-talkie was a prop, the trees were our backdrop and my fear made it a thriller.

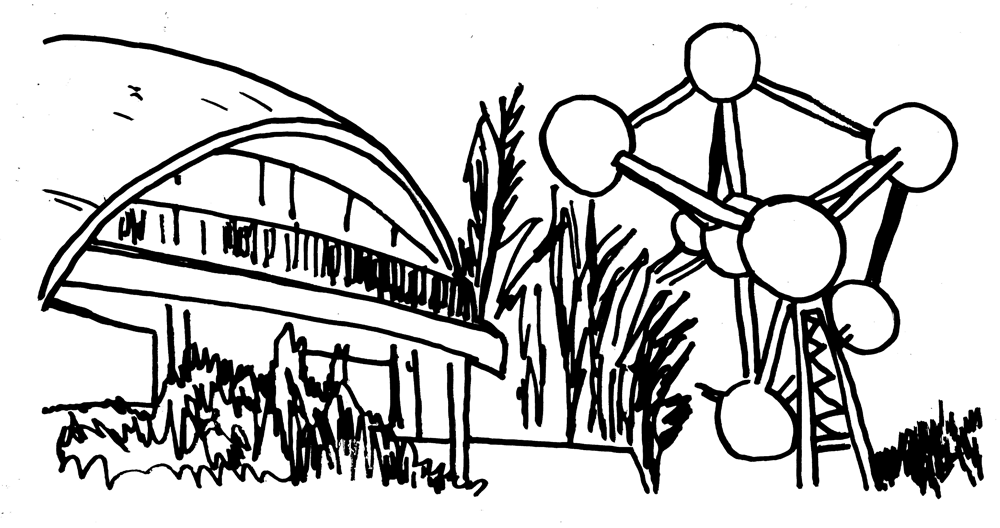

What came next, dear Dominique and dear Ari, was an extraordinary journey through the urban architecture of Brussels. Perhaps, Dominique, you will remember this trip was punctuated by several stops? The first stop was beside the Atomium, at Salon 58, the restaurant built in 1958 by the architect of the Brussels World Fair.

I step into an empty restaurant. Such an amazing place – benches of pink velvet and candles flickering – cannot be deserted. I deduce that they are waiting for me. Shyly, I look at the waiters, seeking any sign. I am Peter Sellers in 1963 as Inspector Clouseau in The Pink Panther, directed by Blake Edwards. With extreme alertness, I walk through the room, expecting someone to stop me or Kato, my valet, to leap out all at once to knock me down… but nothing happens. Bah… I leave.

With a gesture of his hand, my chauffeur suggests that I stay a little longer. No, thank you, I say, but I get the feeling I’m about to start having fun.

The second stop is a little more cloudy – I vaguely remember deserted streets in an industrial zone. And then the car stops in front of a club. Someone at the entrance asks for the K.19 envelope handed to me by the chauffeur at the beginning of this trip. In exchange, I get a drink ticket, and I head inside to a concert of post-punk music. I gather I have time for at least one beer. My driver’s silence means I never quite know how much time I have, nor am I comfortable with the idea of leaving him. Who is he? What is his role? What exactly is my role?

Out of the rectangle

The performance I have experienced, that I describe in the letter, is based on a fine orchestration of several activities that are not visible to the audience participants in K.85. A set of places (rectangles) outside the participants’ knowledge are at work. In this sense, what is out of the rectangle and what is in each rectangle is inseparable. It creates misunderstanding, tensions, drama, and mystery in a rather unpredictable scenario.

The club fills up, the concert starts, and I become Solveig Dommartin listening to Nick Cave in the final concert in Wings of Desire, the film directed by Wim Wenders in 1987; and then I leave my character and step back into my own life. This concert is for me. In my own life, I go to similar concerts sometimes – what a marvellous coincidence then, fiction meets reality, as they say.

My chauffeur waits for me beside the car. When he sees me, he says something into his walkie-talkie and takes me to what will be my last stop.

The limousine parks in front of the side door at the Kaaitheater. A man who’s also carrying a walkie-talkie leads me inside the building and then we rush through the basement of the Kaai at great speed. After a long race through the semi-dark, a door opens: WELCOME, K.19! I am alone on the stage of the Kaaitheater, and before me, the audience applauds. Two thousand people will have seen me naked, or perhaps just one – the effect will have been the same. I’m completely stunned.

Dumbfounded, I’m led to my spot among the audience. As I come back to my senses, I finally understand that the audience in the room is the audience from another part of the trilogy, K.62 (2011). This audience has witnessed several entertaining moments, including the arrival of each participant from K.85. And now I am part of the audience welcoming other members of K.85. A large blackboard beside the stage retraces the itinerary of each K under the direction of a hostess/mistress of ceremonies – the woman with the microphone who welcomed me to the stage – who stays in contact via walkie-talkie with each K.85 escort.

Short-circuit

The moment of opening the door of the theatre and then standing in front of an audience was as abrupt as a short-circuit can be.

Precision

The journey of each member of K.85 has a considerable impact on the whole project. Each becomes like a piece of a puzzle.

That night, K.85 allowed me to simultaneously borrow, imagine, and refuse several roles in my life, and in an endless fiction. I took on various points of view – camera, screenplay, editing, actress, and spectator. Your project, Dominique and Ari, allowed me to enter into the image, to look at it, to leave it behind, to emerge, and then to produce others and so on and so forth. I got to be part of a mobile opera travelling through a city, and your script allowed me to enter myself in various space-times that overlapped in my imagination. Again, a phrase from Vincent Dieutre comes to mind, from his essay Éloge du vibratile (2000, 85): “What remains is well and truly the sensation of an image that is an extension of a body, of a quest.” Yes, it is above all my own body that experienced this story via a score composed so finely by you.

The work I do is not on objects or images, but rather on space-time. And you reminded me of this. I work on choreographic images that only exist through time and movement. My scripts are more like scores.

You said some similar things, Ari, in an interview – whose source I can’t find any more – the two of you had with Dominic Eichler in Berlin in September 2011:

Dominique and I often think of our work together in very musical terms. In fact, we talk more in terms of a score than a script, creating a composition. In the end the piece will be as long as it needs to be.

I think of your work often, Dominique. Especially that time I was trying to film images I didn’t know yet. This past winter, I did some work with a cinematographer, preparing short films for an installation. My cinematographer wanted to know what images I had in mind. She told me (without reproach) that the cinematographer usually has a screenplay in hand when she approaches her work, and knows what she will be filming. With me, I didn’t yet know the images I was going to film. I wanted to discover them through the process, but this was unusual.

Rectangle

The driver was in constant communication by walkie-talkie with the mistress of ceremonies (MC) in the theatre of K.62. Inside, the audience were following the itinerary of each K in their own space (rectangle) on the MC’s blackboard.

To edit

The composition involves the score of the whole performance of K.85 and the score of K.62.

For the K.62 audience, the performance is based on the precision of the one in K.85. The composition involves the score of the whole performance of K.85 and the score of K.62.

I refer to the term montage from a technical point of view, as a method of assembling images, whereas I refer to the term choreography for the organization of gestures and objects, but I could just as easily say that I “choreograph” the images and “edit” the movements, and that asynchrony is the effect resulting from montage.

As choreographers, we simultaneously occupy the functions of screenwriter, director, and editor of our work, without any hierarchical distinction, and without giving precedence to the scenario/content. All of it happens in a fluid alternation between these different processes. And in fact, we don’t even conceive of these functions in an atomized way – the direction or the scriptwriting happen during the editing process just as much as it does as during the process of producing the material. There is a permanent come-and-go in play between these roles. Of course, the degree to which each artist works in this way varies. But articulating this has clarified even further the close links between choreography and asynchrony.

As I wrote to you today, I took my place once more in the back seat of my Polyphemus’ limousine. But what’s more…

I read the news today, oh boy

About a lucky man who made the grade

And though the news was rather sad

Well I just had to laugh

I saw the photograph.

He blew his mind out in a car

He didn’t notice that the red lights had changed

A crowd of people stood and stared

They’d seen his face before

Nobody was really sure

If he was from the House of Lords.

I saw a film today, oh boy

The English army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

I’d love to turn you on.

Woke up, fell out of bed,

Dragged a comb across my head

Found my way downstairs and drank a cup,

And looking up I noticed I was late.

Found my coat and grabbed my hat

Made the bus in seconds flat

Found my way upstairs and had a smoke,

Somebody spoke and I went into a dream.

I read the news today oh boy

Four thousand holes in Blackburn, Lancashire

And though the holes were rather small

They had to count them all

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall.

I’d love to turn you on.

A Day in the Life by the Beatles in 1967, mm… forgive me, I hadn’t heard this song for so long. It’s playing now in the café where I’m writing. No doubt there’s a little drama, a little story, a little Beatles in your projects, Dominique. You are not an abstract artist as I am. Your work draws upon stories that you disassemble and that we, the audience, put together in turn. Above all, you create environments – I know you prefer this term to the word “installation.” Personally I prefer the word “project”: that allows us, the – what should we be called? – participants/visitors, to appropriate, take apart, and then put back together the images and leave them behind. My deepest thanks to you, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster and Ari Benjamin-Meyers.

Lynda