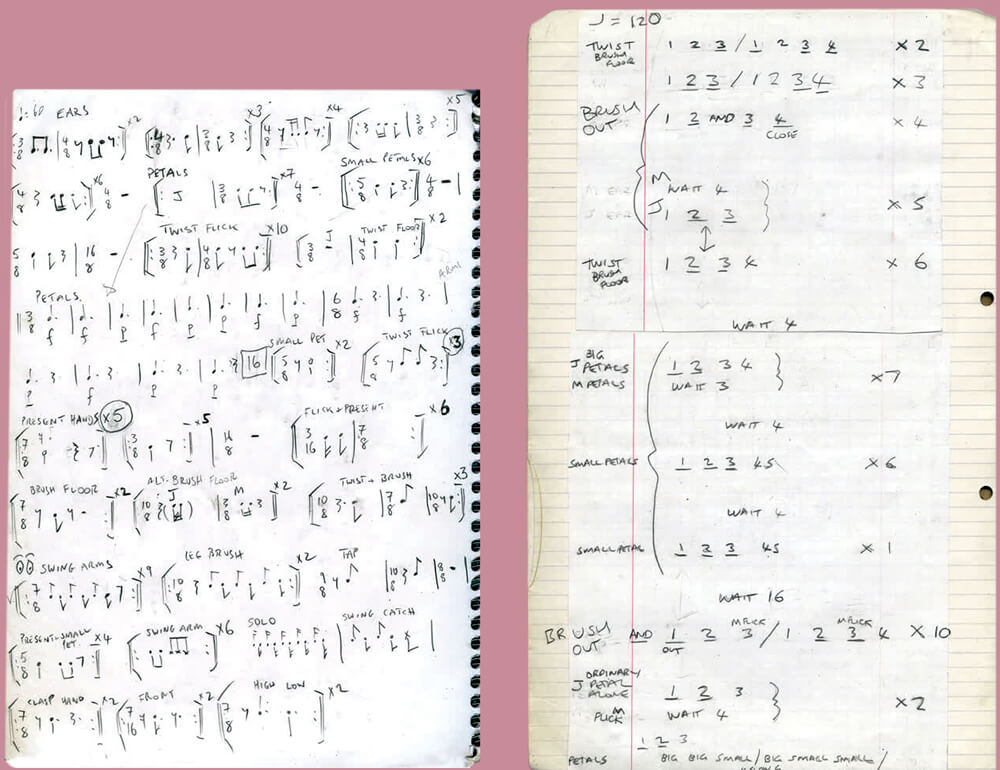

Both Sitting Duet is a 37-minute silent gestural translation of the score of Morton Feldman’s violin and piano piece For John Cage, the repeating rhythmic movements of which seem to cause a kind of synaesthesia, where music is heard though none is present. The piece is concerned with how the counterpoint between two moving bodies might be read, and attention is held throughout by small but significant shifts of gesture, rhythm, and dynamic between the two performers.

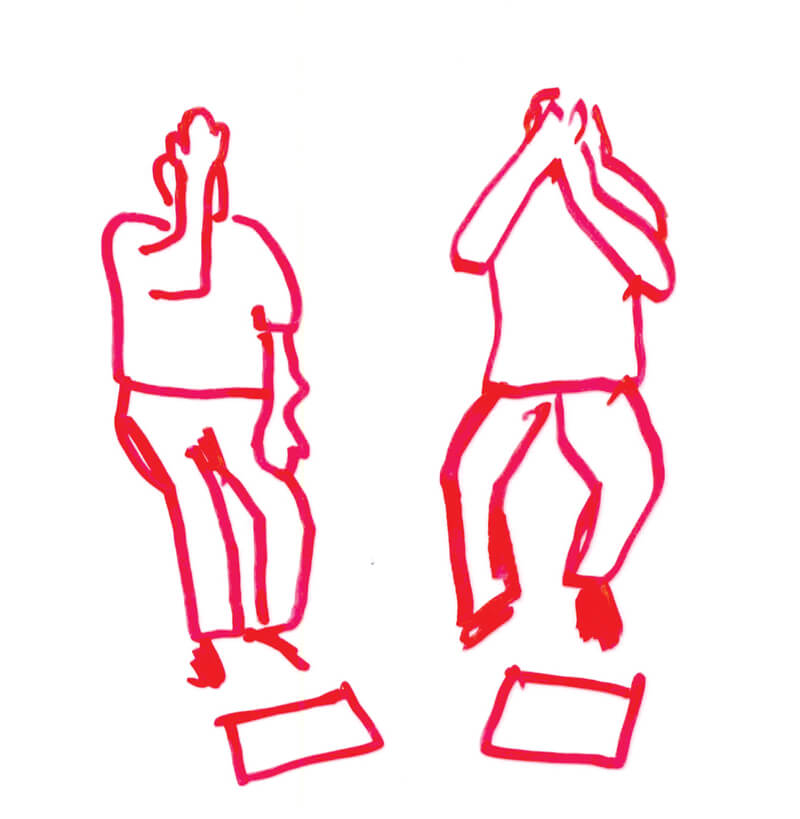

In this sense the element of slight surprise in the piece is continuous, made more evident by the minimal materials used. Eight minutes before the end however (around 32’40” on this Vimeo link document), a larger shift takes place and silent gesture is replaced by loud clapping. This loud clapping introduces perhaps the real moment of unpredictability in the piece, when the clapping rises to a rhythmic shouting, which appears as a kind of dramaturgical relief after the long concentration that has preceded it.

Body Not Fit For Purpose is a 30-minute performance of short gestural dance solos accompanied by mandolin, each of which is introduced with a political title that seems to imprint a narrative upon the abstract movement. The titles/solos are edited into an order which gives a kind of dramaturgical progression, sometimes serious and sometimes humorous. It remains slightly unclear throughout the piece what the relationship of the two performers is to the materials being used, but the final title dedicates the performance to “my father, who for my 10th birthday bought me a copy of The Communist Manifesto and Chairman Mao’s Red Book.” The surprise of the arrival of this more direct personal narrative anchors the previous game with language and retrospectively gives permission for that game.

Jonathan Burrows & Matteo Fargion

Montreal, 13 June 2016

Dear Jonathan, dear Matteo,

We don’t run into each other anymore, and I miss you and your work. Although we weren’t that close, you were present in my life, and your friendship, even peripheral, grounded me, and gave me courage to persevere in my own work.

For my part, after closing my dance company, I decided to take the time to write about my choreographic research. I chose to do it within the framework of a doctoral degree, otherwise I never would have found the time. Maybe you’ll remember our conversation around the time of Out of Grace, Matteo: for or against the PhD in Arts? In the end the choice was made and leads me today to Jonathan and yourself; as I unpack my research, I realize that you two are a part of it.

This research currently takes the form of letters addressed to artists whose work has impacted my own. As you know, Jonathan, your work has always had an influence on me. And I had the luck to work with Matteo on the creation of the scores for my projects Encyclopœdia DOCUMENT 4 and Out of Grace. Both experiences have had a lasting effect on me – a lesson I can sum up as an ode to detail and rhythm. I remember your daily motto, Matteo, “exhaust the material”: restrict yourself to using a single material at a time, exploring it patiently before moving on to another. In the end, what you taught me was very simple: love your material.

Love it by giving it your time, by finding its relevance in time; how a movement, for example, dictates its own time, or, inversely, how a rhythm forges a movement. A movement of the hand, a glance, a gap in action, a thing, even – and in fact above all – an insignificant one, becomes, through this approach, noteworthy because it is placed in a time and chiselled by this.

Glitchy pebble

Mistakes, glitches, errors, details, and unpredictability are of great value in asynchrony. They are life attractors. Even if these works are finely written in a score, errors during the performance are part of it.

EXCERPTS

Both Sitting Duet. (2002). https://vimeo.com/68204508

3’55”, 23’34”–24’00”: Matteo Fargion laughs.

There’s so much to say about the work you’ve developed as a duo. Excerpting one aspect isn’t easy, especially in this epistolary form, and requires, I must admit, a certain amount of audacity.

Your style.

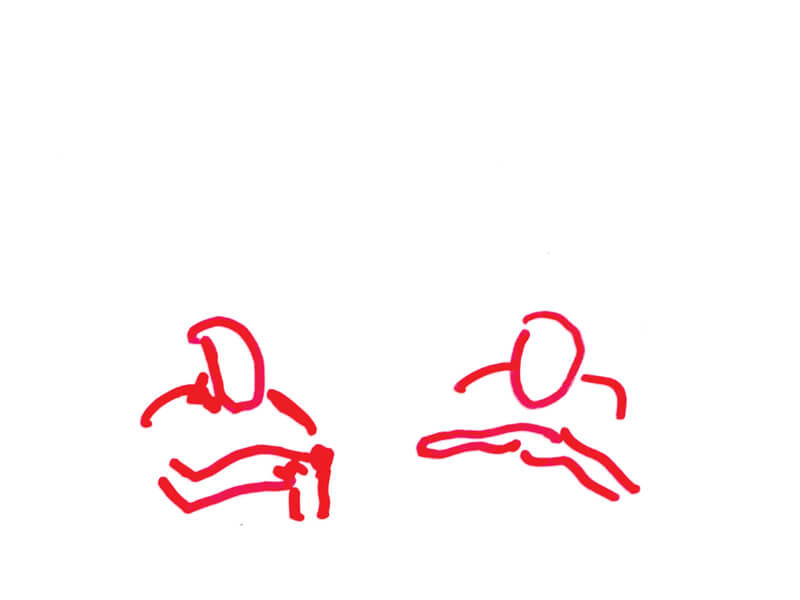

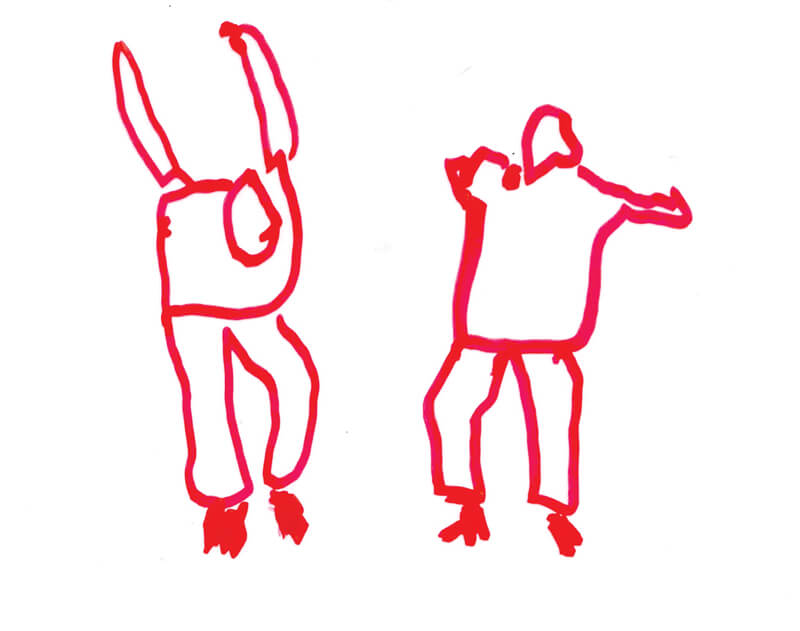

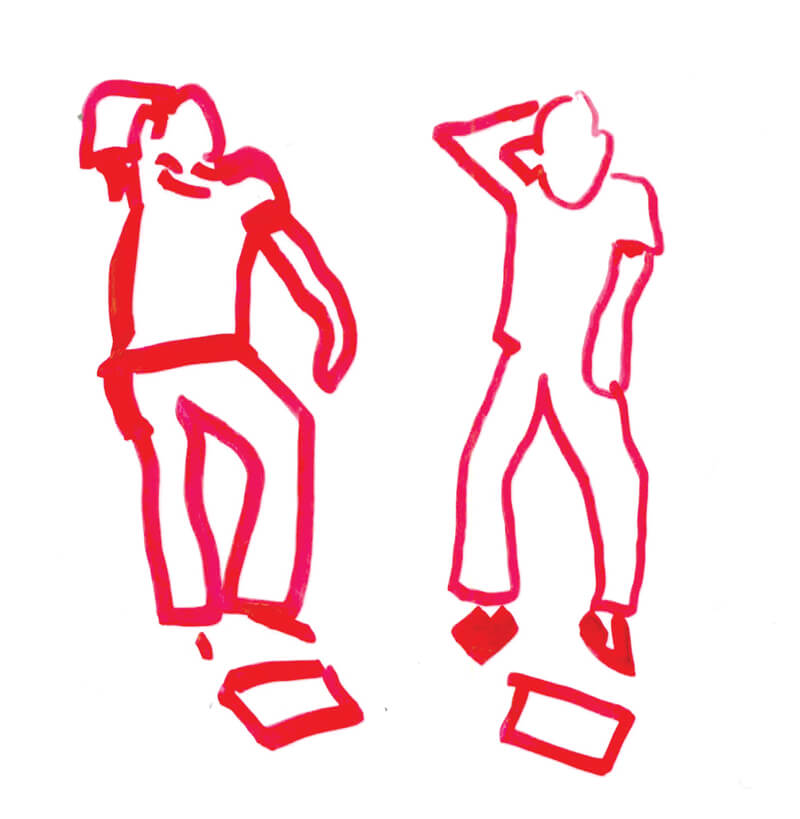

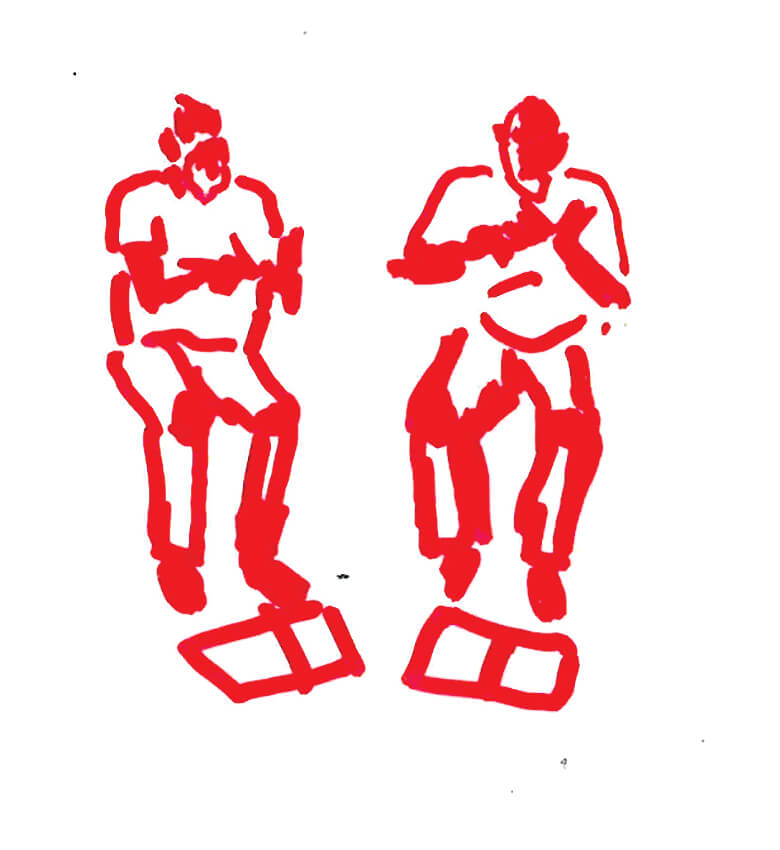

Yes, this must be it. You are at once classical and eccentric artists. Your compositional approach is profoundly anchored in the musical structures you blast open and divert. An eccentric – an “original” as they say – is not named as such only because of what s/he does or is, but also because of what s/he produces, and you two are the perfect example of this. No conspicuous show of eccentricity characterizes your duo. You appear on stage in ordinary clothes, and the choice of movements is almost banal. And yet. A closed fist, a little vibration of the wrist, a raised arm – all become extravagant. Eccentricity is located in the assembly of gestures and the derailments you impose upon movement. A gesture we think we recognize becomes fantastical because of the choice of execution, which verges on the absurd, or through the exaggeration of a detail. I would even push this idea a little further – if only to break the ice – and compare you to dandies. The definition on the French Wikipedia page today is interesting: “the word dandy appears at the end of the 18th century (in England), distinct from eccentricity – it plays with the rule but still respects it.” Your compositions are remarkably zany and loquacious in regards to this idea.

The structures and protocols of music and dance underlie your work, and anchor your creative process. And as abstract as your pieces can be, the audience finds itself within them. The rhythms – I was going to say the punctilious rhythms – grab the audience, who become more and more captivated by the smallest detail of what is introduced on stage. Your pieces command attention. The silences in your danced scores become striking moments of tension, all the more exquisite because anything could happen.

Eccentric pebble

Here some examples of unconventional, marginal, queer, wacky, bizarre movements.

EXCERPTS https://vimeo.com/68204508

7’43”: After quiet sequence, the performers start an abrupt movement of the arms – let’s call it the monkey movement. This movement suddenly opens the space behind their bodies.

13’12”: JB and MF start tilting their heads.

14’46”: Wiping their faces.

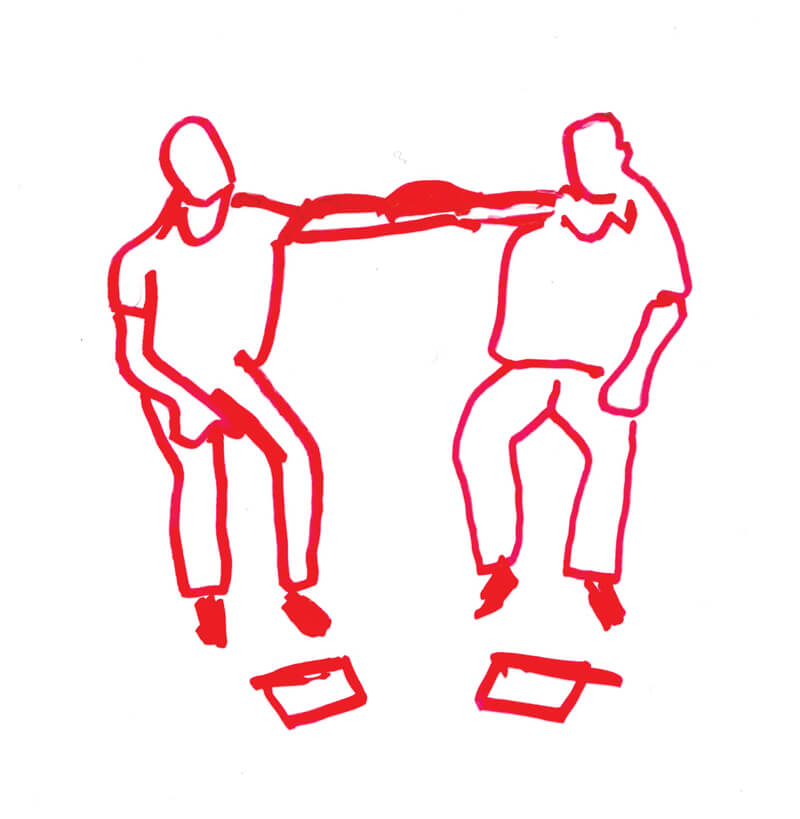

16’20”: Holding hands.

For more than fifteen years the two of you have worked to disrupt gestural and musical material as though these were mechanical objects. Through a multitude of rhythms borrowed from existing musical scores – I’m thinking of scores by people like Morton Feldman – you have been developing a radically simple gestural vocabulary that is precise and profoundly playful. As spectators we observe a dance of gestural units, waiting silently to perceive a moment of unison or, better, a slight adjustment, whether of the eyes or some personal tic, that allows us to step outside the frontality of the show for a moment and see you as individuals.

A system of composition such as this cannot forgo accidents and, in spite of the desire to “perform” your scores, you integrate error, you even count on it, even if only in your attempts not to produce it. You set in motion a complex system of details with which we, the spectators, grow familiar. But this system induces disturbance and, sooner or later, something will become unhinged. The strength of your work lies precisely in its programmed self-destruction which, by a ricochet action, generates a force of attraction and attention between the work, you, and us, the audience, at every moment. We wait for the miraculous instants of synchronization and even more, of desynchronization – this is what defines your style, so spirited and offbeat. Your work wouldn’t mean anything without precision, but it’s such a particular kind. Normally precision takes us into a rather dry, sterile territory that can quickly become lifeless. But you employ it with the most communicative virtuosity that a formidable empathy is produced in the spectator, just as it is between the two of you.

And so on. The choreography is composed of simple movements that become unusual and eccentric in the context. The effect produces curiosity, smiles, hilarity. The whole composition is made up of a set of pebbles that follow one another and that manage to produce surprise.

My point of view is of course personal, but these two artists created one of the best examples of work around surprise and unpredictability. It is useless to dissect the pieces to show a pebble , an eccentric action , an anachronism – their work is full of them. A viewing of their work is eloquent.

Eccentric, yes. And this extravagance isn’t found only in the surprising rhythms, but also in movements that are astonishingly simple and original, based on trifles. Desynchronization occurs mainly through the details, causing the audience to remain on the lookout, at the edge of their seats for the least sign, as wacky as it may be.

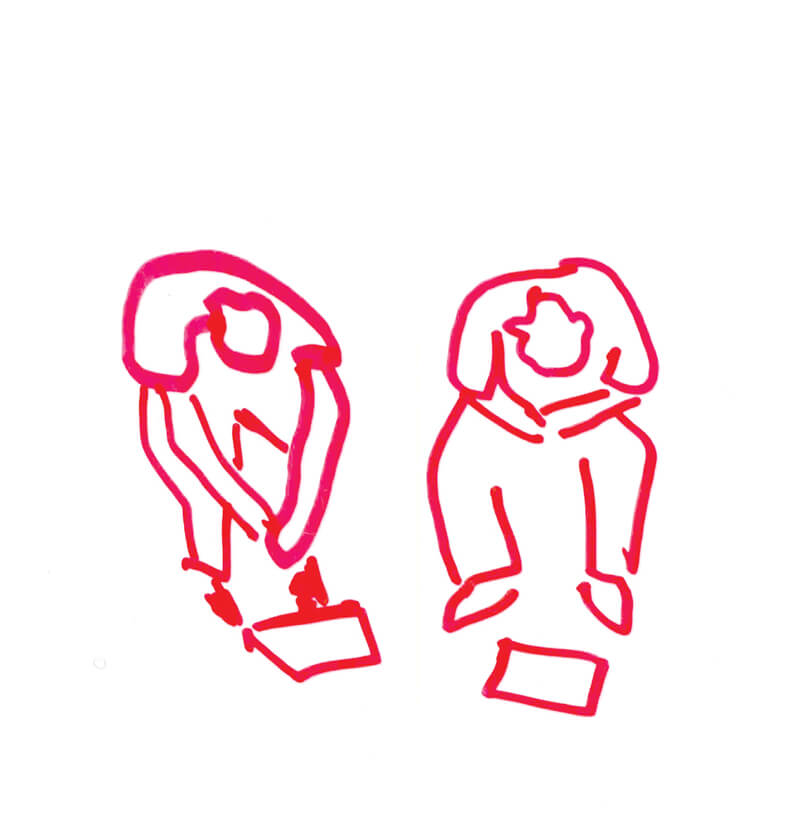

I can still see you both in your first duo piece, Both Sitting Duet (2002), each of you on your chair before the audience, moving parsimoniously, one gesture at a time.

I’m sure you’ve heard of Vivienne Westwood. The London stylist transforms classic style through detail: a colour, a fabric, and above all a spirit of exaggeration, takes over a piece of clothing and transforms it into the most eccentric of trappings. Granted, Westwood’s eccentricity is baroque and even opposite to your minimalism – but whether it’s through excess or measure, both your creations make us smile in their mad freedom, their audacity.

Smiles and laughter are the unmistakable, wonderful result of your asynchrony through detail. Thank you, Jonathan, and thank you Matteo.

Lynda

There is a fantastic out-of-the-blue moment, an anachronic pebble at 32’38”, where MF and JB break the quietness, unexpectedly.

This specific moment in the piece clarifies notions that are not always easy to separate, such as, what is the difference between an eccentric and anachronic pebble ? They are pretty similar. But here, I prefer using anachronic pebble, because not only is the action original, but it is rather inconsistent. It looks like there is a sudden chronological gap in the piece. The anachronic pebble is indeed unconventional, but has this little plus: a quality that relates to time.

In this approach, playing with a parameter conducts easily to another one, cumulating into anachronism and an over-the-top situation. This can end up in a short-circuit moment.

The work of JB and MF involves working with repetition and exaggerated use of repetition that goes over the top with a short-circuit moment.