Bogliasco, 14 February 2015

Dear Alberto,

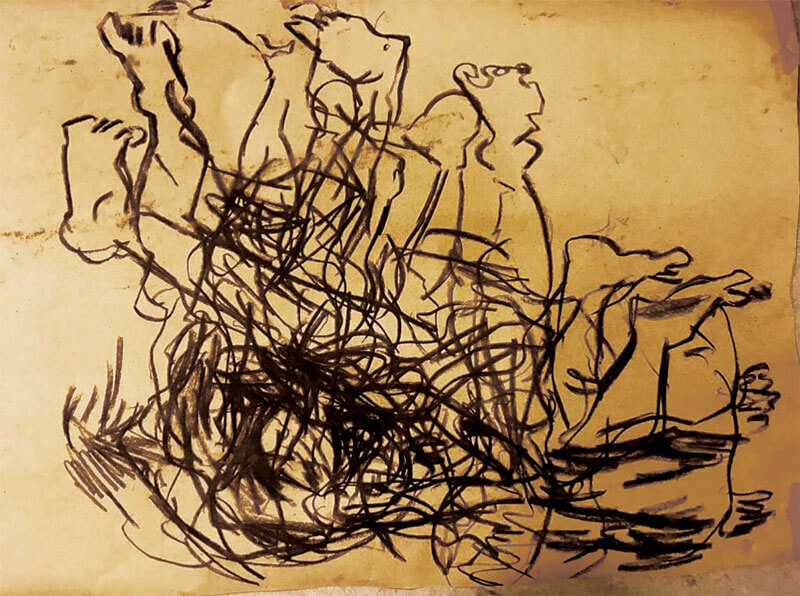

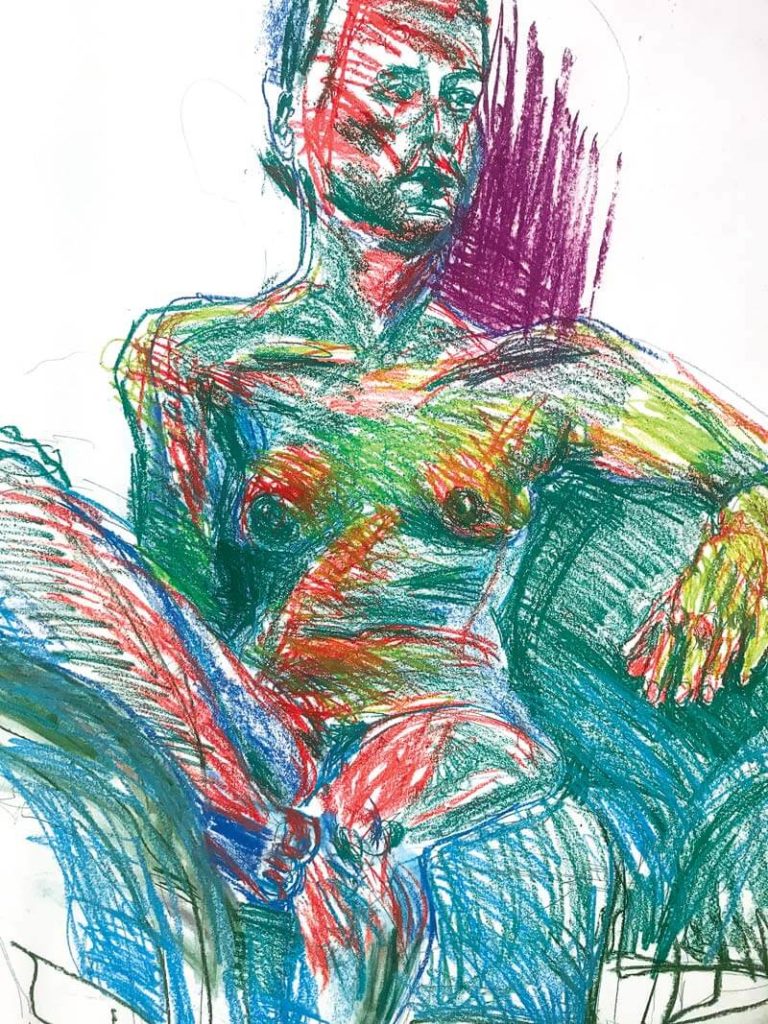

I feel somehow so close to you, as though you’ve become a member of my family in spite of yourself. Would you have adopted me? You are, in any case, a part of my life. You came in without me expecting it, as one says of a child who arrives by accident; the father of an artist by accident, a retroactive father. I don’t remember how I came to discover your work – probably through one of your portraits that crept into my line of sight one day. Your drawings are tremendous, you know – they ravish the space of the person who looks at them. They have no reserve; they enter and inhabit the space we believed to be our own. Just this morning, for example, I pinned two photocopies of your drawings to the wall, one of a woman standing and the other a portrait of Annette. And even with the poor quality of the photocopies, they captivate me. To be completely honest, they disturb me. I have this irresistible urge to look at them rather than write to you. My eyes keep coming back to them. Their black lines act – I was going to say again – in a retroactive way, almost as though the drawings hadn’t completely given themselves over, or as though my experience wasn’t yet complete. Maybe it’s a bad idea, in the end, to sit facing them while I try to write to you.

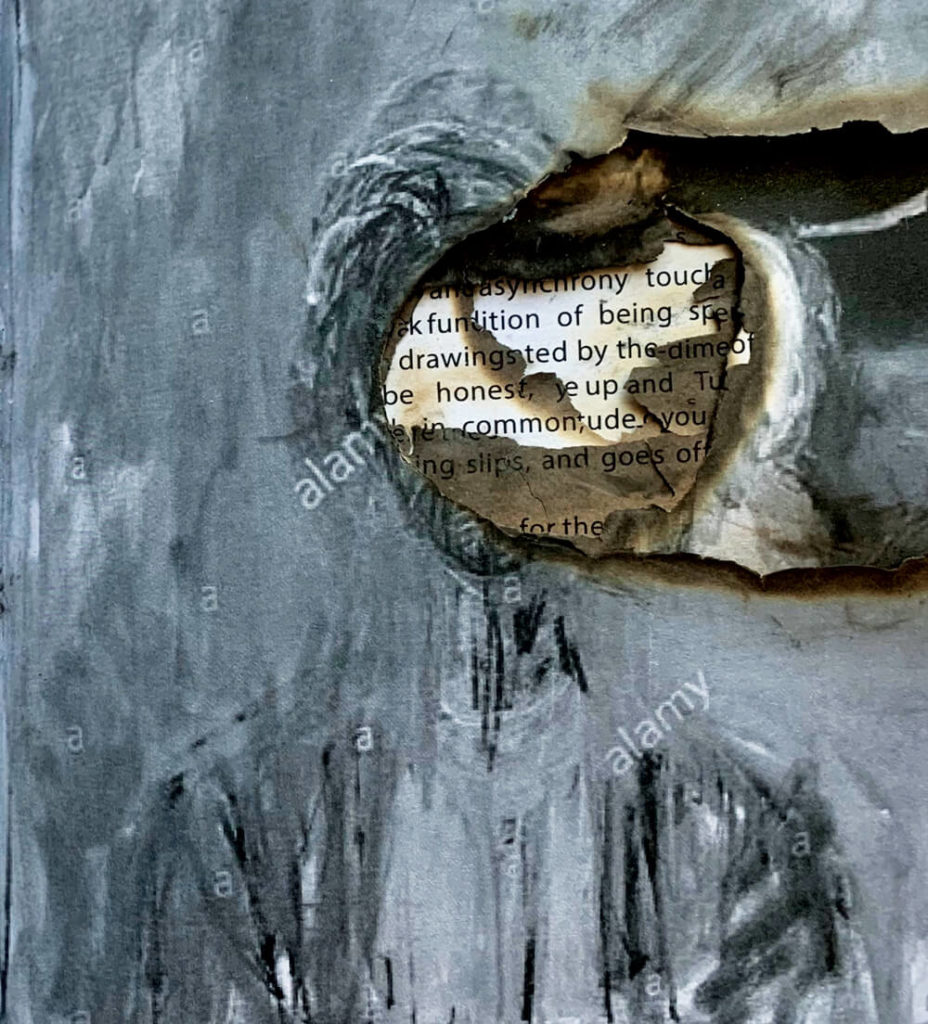

In spite of their power of attraction, your drawings are not magic: they’re simply valiant. And stubborn. It’s hard to explain, and I’m trying to understand it myself: a drawing will draw and redraw itself right before our eyes, following the multiple lines that make it up. It erases the space from before by superposing itself over the top, and reconstructs another space. Your drawings proceed by self-destruction. Were you familiar with the self-destructive art of Gustav Metzger? His approach comes to mind, you two would have got along. Maybe you knew each other? His manifesto from 1959, Auto-Destructive Art, is on his site http://radicalart.info/destruction/metzger.html. In it I read: “Self-destructive painting, sculpture, and construction is a total unity of idea, site, form, colour, method, and timing of the disintegrative process.” Disintegrative process… exactly. Your work doesn’t produce static objects – they are works in the etymological sense of the term: operare = to work, and we do so along with them. When we come into contact with them, we find ourselves in the very process of the object (an object being, from my point of view, anything: a page, a drawing, you, me, a sculpture, an idea, and so on). The primary purpose of your art resides not in the form, but rather in the sensation it provokes – or at least I want to believe for a moment that my work allows me to understand yours. Even though, years ago, I hung from the fence in front of your studio on rue Hippolyte-Maindron to catch a glimpse of your work, I would never have dared to show you mine. I prefer the discreet intimacy of my work alongside yours in my artistic genealogy. But let’s come back to your oeuvre: form is eminently important, of course – if not, why be an artist? – but is the result of a process in space. And it is in this way that your work illuminates my thinking.

The experience of the object is possible through a continual creation of space, and the inverse is equally true: the experience of space is possible through the continual creation of the object. Space and object are thus inextricably linked, and in perpetual reconstitution before our eyes. When this is working, we are able to perceive a space that is dynamic, alive, and in tension. In other words (and you know this better than I), the artist creates a kind of equation in space, based on materials, air, silence, movements – anything can be used – and the finished work corresponds, we might say, to a formula in space; we, the spectators, perceive with our senses that which the artist puts forth; then art historians take over and analyse all this; and then the artists themselves respond as well. But there’s one aspect that catches my attention, and it is the notion of space as a disjunction of several space-times. Space is perceived, seen, and lived through a process of differentiation, in which we, the objects, and the spaces of all kinds – colour, in particular – are incessantly rearticulated by movement; that of our bodies first, but also the movement the artists (such as yourself) propose in their objects.

Your drawings, Alberto, are neither sensible nor quiet – they don’t want to become fixed images. They make us enter into the creation of their space. Your portraits catch and hold our eye; their faces insert themselves into our space without a speck of politeness. They are true “space killers.” They ravish our space and monopolize our attention with the insistence of their repeated and obstinate features. In no way is space, in your works, taken for granted.

How does an object or a drawing capture our attention? How does an object assert itself in space? Artists like Metzger and yourself allow us have a relationship to space through the intrinsic experience of the latter. You work space as a material, and for this you use recomposition. Your drawings must constantly remake themselves – it’s the only possible way we can see them – time is able to penetrate them as a result of your tireless research. Metzger had a different, more direct approach: he destroyed works before they had the time to become cult objects, as we say, of art and consumption.

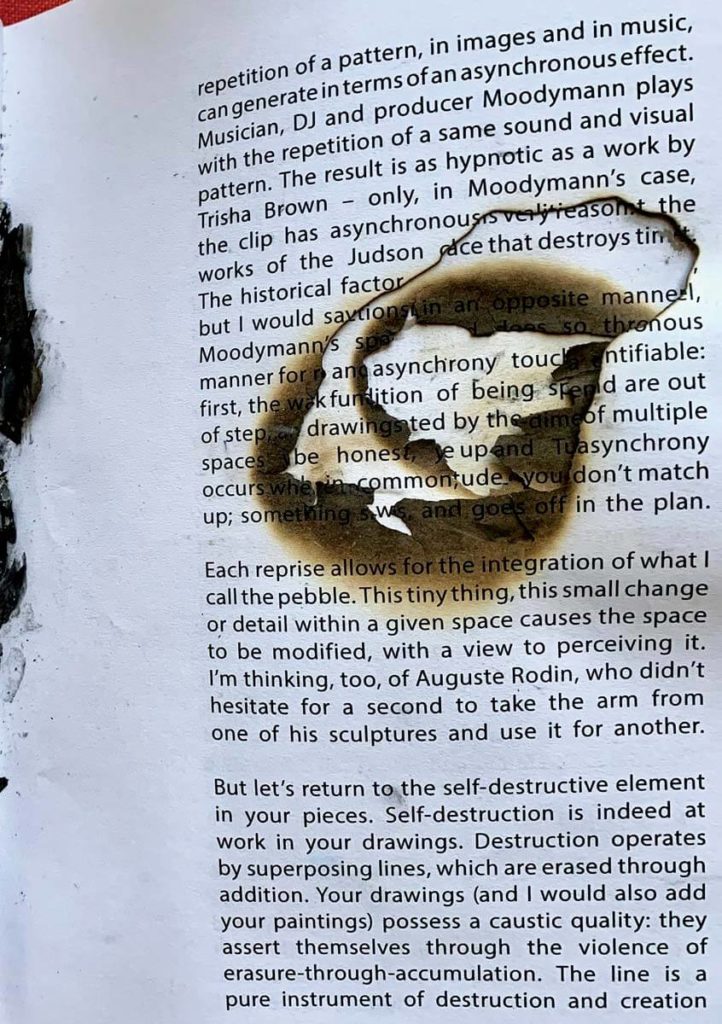

I am a proponent of the reprise as a work method applied to a given material, contrary to the repetition that I tend to associate with composition. The reprise is a way of working, and not an aesthetic language. In dance, for example, choreographer Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker (and, long before her, the whole gang from the Judson Theater Church with Trisha Brown and Lucinda Childs) did a lot of work with repetition. The eminently compositional reach of their works takes over. In a completely other aesthetic register, a video I recently watched by Moodymann, Come 2 Me (2014), is an eloquent example of what the repetition of a pattern, in images and in music, can generate in terms of an asynchronous effect.

Musician, DJ, and producer Moodymann plays with the repetition of a same sound and visual pattern. The result is as hypnotic as a work by Trisha Brown – only, in Moodymann’s case, the clip has asynchronous qualities that the works of the Judson choreographers don’t. The historical factor plays into this, of course, but I would say that on a purely formal level, Moodymann’s clip operates in an asynchronous manner for reasons that are clearly identifiable: first, the way the image and the sound are out of step, and second, the placement of multiple spaces within the frame. The asynchrony occurs where the sound and image don’t match up; something slips and goes off in the plan.

Each reprise allows for the integration of what I call the pebble. This tiny thing, this small change or detail within a given space causes the space to be modified, with a view to perceiving it. I’m thinking, too, of Auguste Rodin, who didn’t hesitate for a second to take the arm from one of his sculptures and use it for another.

But let’s return to the self-destructive element in your pieces. Self-destruction is indeed at work in your drawings. Destruction operates by superposing lines, which are erased through addition. Your drawings (and I would also add your paintings) possess a caustic quality: they assert themselves through the violence of erasure-through-accumulation. The line is a pure instrument of destruction and creation of spaces. The dynamic of movement of the line allows us to enter into the process and into the constitution of space in time. And so, your drawing of Annette becomes a living drawing because it exists in time, and the discord between the different spaces at work is the result of several successive operations. I come now to a phenomenon that interests me more than anything: the destruction of space by time. But I’d like to begin with its opposite: the destruction of time by space.

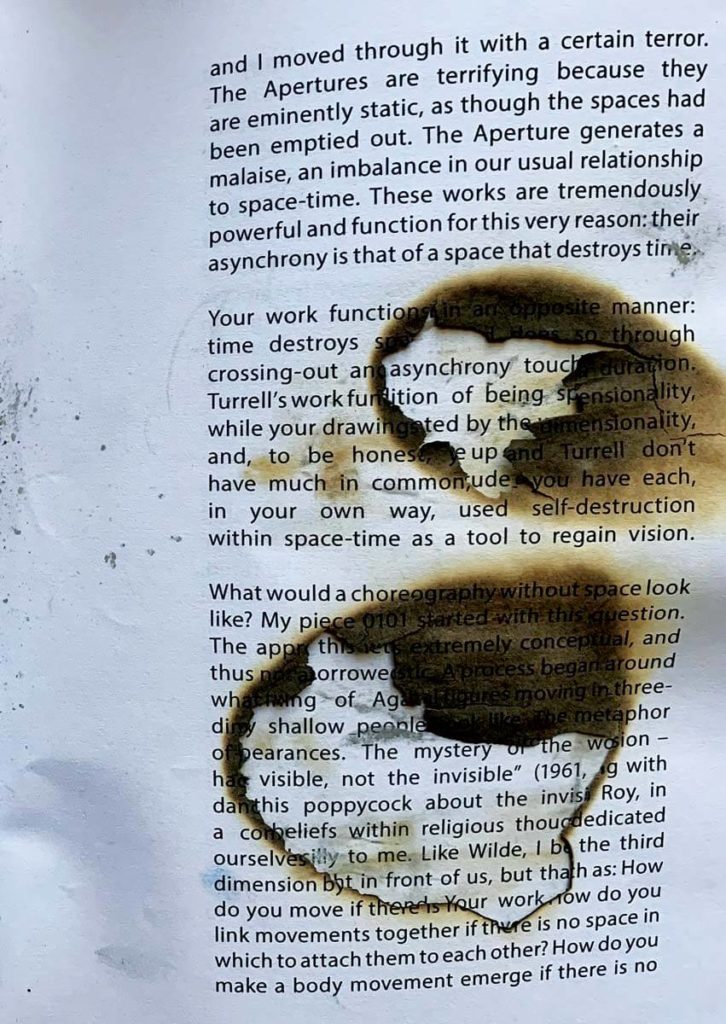

A particular situation comes to mind: I remember being in a gallery in Paris in 2004, in one of the Apertures, Cherry (1998) by James Turrell, and, because I am claustrophobic, I remained frozen at first at the opening of the installation. When I went in, I could see a space filled with red light with a rectangle somewhere at the back. Turrell presented the viewer with a space without borders. An opening at the end of a room was the only reference point for viewers to situate themselves spatially. A very dense light, a monochrome of red, filled the space. As I took a few steps forward, I felt the strangeness of the space, and felt what I would call a cognitive malaise; My body did not understand this space at all. In Turrell’s installation, there was a disjuncture between space and time, as though the space destroyed the time; and so the space of the installation conquered the body of the viewer. Turrell’s experiential work achieved the incredible feat of making us produce, in our own bodies, the element of destruction. In this space, time seemed horribly suspended, and I moved through it with a certain terror. The Apertures are terrifying because they are eminently static, as though the spaces had been emptied out. The Aperture generates a malaise, an imbalance in our usual relationship to space-time. These works are tremendously powerful and function for this very reason: their asynchrony is that of a space that destroys time.

Superposing lines on a canvas, over and over again, produces a vibration, a sort of movement on the surface that tickles our attention.

To erase

Erasing is a way to perturbate the equilibrium in a given space. Giacometti works through accumulation by superposing information (reprise, repetition, overdose, etc.). The accumulation of lines generates much vitality in the drawing.

The glitch between each line produces some sort of vibration, a small movement that engenders a temporal awareness. The portraits become vivacious; we can’t help not looking at them. They retain our attention.

To erase by accumulation and superposition

A drawing will draw and redraw itself right before our eyes, following the multiple lines that make it up. It erases the space from before by superposing itself over the top and reconstructs another space. In this regard, I like to think of his drawings as self-destructive. The movement of recomposition destroys any idea of the portrait as an object in favour of portrait as process.

Over the top

Thus, the multiple pencil strokes and the abundance of lines in each of Giacometti’s portraits do not leave one indifferent. In some respects, the strength of Giacometti’s portraits resides not in the form, but rather in the sensation they provoke. And that sensation is possible through intensity that comes from doing over and over again and through a lot of attempts on the same canvas.

Your work functions in an opposite manner: time destroys space, and does so through crossing out and slow work over a duration. Turrell’s work functions in three-dimensionality, while your drawings act in two-dimensionality, and, to be honest, you and Turrell don’t have much in common, but you have each, in your own way, used self-destruction within space-time as a tool to regain vision.

What would a choreography without space look like? My piece 0101 started with this question. The approach was extremely conceptual, and thus not at all realistic. A process began around what two-dimensional figures moving in three-dimensionality would look like. The metaphor of removal of a space – the third dimension – had led me to approach the body, along with dancers AnneBruce Falconer and Ken Roy, in a completely eccentric way. We dedicated ourselves to the mission of erasing the third dimension by exploring questions such as: How do you move if there is no depth? How do you link movements together if there is no space in which to attach them to each other? How do you make a body movement emerge if there is no three-dimensional space outside this body? To “succeed,” if I may call it that, the dancers made movements of less than one second and thus the movement didn’t have time to inscribe itself in space. A gesture would emerge so quickly it was like a spark we couldn’t locate in the space. The effect was incredible. A little like in your drawings, Alberto, viewers weren’t entirely sure of what they had seen; they watched the dancers with curiosity and ended up waiting, along with them, for something to happen. Your drawings carry this implosion within them – they seem to exist only for a furtive moment. This may be the reason why my eyes keep coming back to them.

Self-destruction

Destruction operates in the drawings by superposing lines, which are erased through addition. In Giacometti’s portraits, the space is a disintegrative process that works over time, through gestures that are superposed on the top of each other. It creates a little glitch between the lines.

In 0101, the movement of the dancers and the space was never complete; something that would allow the space to become realistic was always missing. Depth was obliterated, movements were separated coldly, and the dancers had a quick and sharp way of moving, without any fluidity. And in the end, just like your standing sculptures, Alberto, the dancers nearly always remained still. By conceptually separating space and time, there was no longer any reason to move. In attempting to destroy a space, I had ended up making a piece about space, and the bodies in it became real space killers themselves, like your portraits, remaining there, right in front of us, stock still.

Thus, space is not this vast and empty thing we penetrate, as we learned in expressive dance classes, but is rather a result: the result of a piling up of spaces and time that are not at all synchronized. We try (ardently, in good faith, and in spite of everything) to synchronize ourselves with one another and with objects, but it’s all very demanding: our experience in space is different, and we live in a permanent state of desynchronization. Artists have allowed me to understand this, and you were the first among them. When we synchronize with each other, we flatten everything. What is this old-fashioned and terrible notion of harmony?

My research into asynchrony touches on this permanent condition of being spatially out of step. I get captivated by the works of artists who, like you, never gave up on their sensations and never feared the solitude of their language. They knew, just like you, that it is in perception that we all converge. The painter Francis Bacon, who you knew, alluded to an art that would speak directly to the nervous system of the viewer.

I will end this letter with a quote from Susan Sontag, borrowed from Oscar Wilde at the beginning of Against Interpretation: “It is only shallow people who do not judge by appearances. The mystery of the world is the visible, not the invisible” (1961, online). All this poppycock about the invisible and such beliefs within religious thought always seemed silly to me. Like Wilde, I believe that reality is right in front of us, but that it erases itself in each second. Your work sheds light on my research, Alberto – you help me to understand that space is not static, that it is not an object, any more than a drawing is a lifeless piece of paper. Understanding with one’s senses involves experiencing something. Sontag writes in the same essay: “Interpretation takes the sensory experience of the work of art for granted, and proceeds from there. This cannot be taken for granted now.”

Seeing cannot occur without violence. This accumulation of spaces that self-destruct produces movement and time and so, Alberto, your drawings insert themselves into the time of our space. A time occurs and the movement of the gaze is possible, without which your drawings would remain mere objects. Your drawings have helped me to understand the life of a space. Your insistence on wanting to translate that which you saw before the knowledge you had of it informs each of my projects, even when I’m not thinking about it. The tenacity of your vision provides support for my exploration. Your work allows me to understand that space only proceeds from movement; more importantly, time allows things to exist, and allows us to integrate ourselves into it. Beyond all this, we are but poor, lonesome beings without space.

Lynda