On error, space, and ikebana in the making of a theatre play

In the flower shop, Helsinki, 15 June 2020

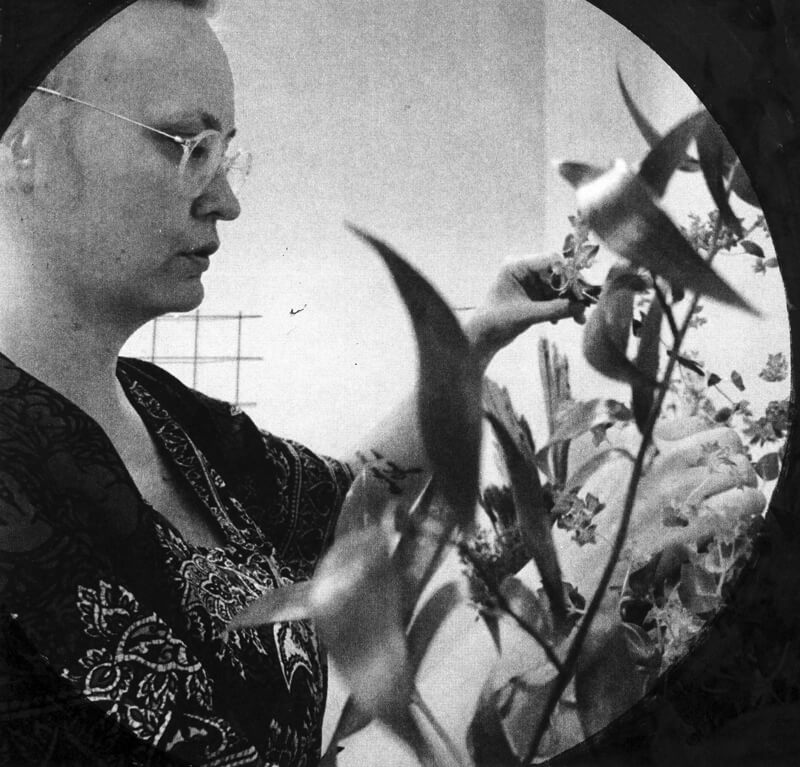

Ikebana

Making alive again something that is taken away from life. The flowers have been cut for the arrangement and they will die. They remind us of impermanence. The Japanese ideogram for arranging flowers is ikeru, which means and is usually translated as “making alive” or making come to life. But interestingly, ikeru can also mean to “transform.”

In ikebana you work with flowers that are dead. And then you bring them alive again. In theatre we have to do some strange alchemy that create life. You have to be doctor Frankenstein. You have to construct it very carefully.

In ikebana, there is this wabi-sabi – did you hear about it?

This is the beauty of the incompleteness. The beauty of the disformed. There would be the tea ceremony, with teacups a little bit disformed, or wood disformed.

In Japanese aesthetics – especially in those influenced by Zen – incompleteness or failure is seen as an important and meaningful aspect of beauty. This quality of deformation and worn-outness is known and appreciated as wabi-sabi. Accordingly, the beauty of asymmetry, incompleteness, and brokenness are much appreciated qualities.

This aesthetic of incompleteness is present in architecture, teacups, haiku, and tanka poems.

Wabi-sabi aims for aesthetic experience that reminds us of temporality and impermanence, and the acute feeling of beauty that comes from that. People think it is about nature, but actually it is a lot about temporality, which brings to theatre.

In theatre – unlike in many other forms of art – people love mistakes. Mistake makes the “now” moment come alive.

First, we must create rules to be able to break them. Mistakes cannot become visible without order. There has to be a balance between order and chaos (mistakes). If an expectation of “how it should be” has not been built you cannot allow for a mistake that is meaningful.

Mistakes in theatre and performing art are a way to make people remember this: “this is not a recording, this is unique, this is temporal, it will disappear, we are together in the same space, so my mistakes will affect you and it is a bit dangerous.”

At this moment of our life, mistakes are important. It is time for people to wake up from their recording dreams… music is recorded, TV is recorded, everything we watch from our phones is recorded. So, for me mistakes are a way to bring people back to this shared moment of now and to make us remember that we are temporal beings ourselves, far from perfection. Our lives happen in the unique now, in the midst of mistakes. This feeling of our shared temporality and mortality, and the beauty that comes from this, is very meaningful for me in theatre.

About materiality. What is your relation to materiality and the concept of ikebana that things are very fugitive, almost self-destructive?

Materiality of the stage is interesting. It transforms the thing. The chair is not only chair anymore on stage. Theatre stage open up all the possibilities that anybody or object could have in any time and place.

The materiality of theatre is very strong; it is very concrete, and not abstract. The stage situation is an arrangement in time and space, an arrangement that creates meaning and action.

It comes back to ikebana.

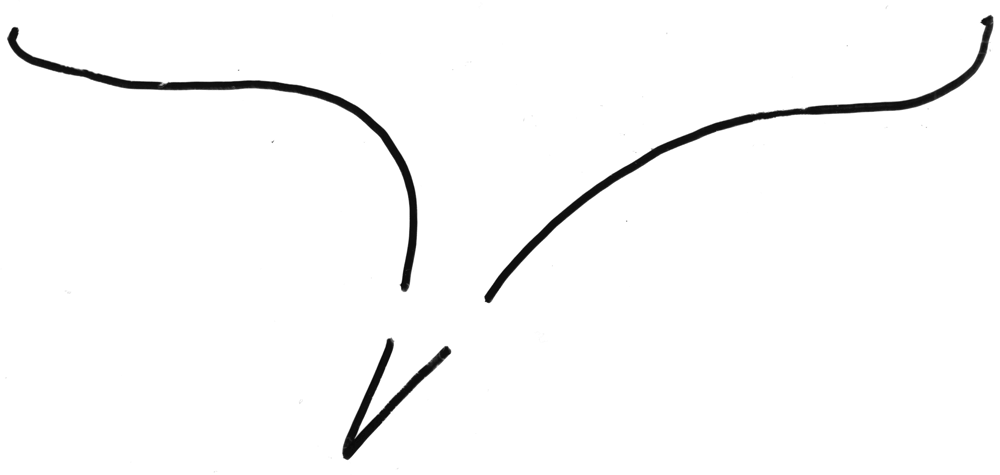

In ikebana everything starts with three main branches. Unequal number is important for creating the dynamic imbalance, asymmetry, the feeling of naturality.

When you have 100% of nature outside, in nature, you don’t see nature anymore. Then you take a branch, and then you prune away 30% of it. You made a choice about what you want us to see from this nature.

Of course, you can take more, but if you want to keep the naturalness, you keep 70% of nature and the end result looks like you never did anything to it. It looks completely natural.

In classical ikebana, you have the sun over the arrangement. So, you decide the place of the sun and, when you make the arrangement, you have to decide which side of it is growing towards the sun.

There are many rules in ikebana and of course you can break them all. They are usually three main branches. The length of the longest branch is measured in proportion with the size/width of the holder. The second and third branch are both shorter and in relationship to the length of the main branch and each other. The vertical degree of each branch is also carefully regulated. The ends of these three branches form a triangle. All these rules are there in order to create the impression of naturalness.