This visual and written resource reflects artistic research into archiving a choreographic process using digital and analogue materials (including bodies). It is a process archive of an archival process with the intent to frame a set of questions. As a practical resource, it might be of use to:

- PhD candidates in dance at the mid-to-late stage in their research who try to bridge studio practice with conceptual and critical enquiry,

- anyone working on multidisciplinary collaborative artistic research,

- artists who work with either existing or emerging media technologies. These need not necessarily be sophisticated systems, but can be the sorts of networked devices like mobile phones used on a daily basis and integrated into creative processes, particularly when the goal is to use media technologies without sacrificing corporeal or somatic depth.

The artistic research at the centre of this resource is the production of a Mixed Reality (MR) archival complement to Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir’s performance of Conspiracy Ceremony – HYPERSONIC STATES.1 The archival work is called Conspiracy Archives and it is currently in its final prototype phase, almost ready to tour either independently or along with the live performance.It is created by the collaborative team of Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir (choreography), Jeannette Ginslov (visual capture and editing), Keith Lim (visual processing and programming) and Susan Kozel (project coordination, philosophy and concept). This resource integrates the voices of the collaborators using words, still images, video and design prototypes. To provide some through-line, the main narrative voice is Kozel’s with indications of when others are speaking. The text and visuals are presented in a sequence coinciding with the project’s development, but the intent is to provide space for readers to focus on what might be of most interest while skimming the rest. All the voices have one thing in common: they depict relationships with Guðjónsdóttir’s work.

1 msgudjonsdottir.com/conspiracy-ceremony-hypersonic-states Dancers: Johanna Chemnitz, Catherine Jodoin, Laura Siegmund, Marie Topp, Suet-Wan Tsang. Music composition: Peter Rehberg.

Instead of offering tasks, instructions or exercises, this resource supports the sort of critical questioning that is often hard to extract once one is deeply embedded in a set of processes, particularly when technologies are used. To this end, Critical Questions will be highlighted throughout. To open out perspectives on the making of a piece that are frequently buried, Process Notes will be provided in the form of phenomenological writing and visual imagery2, with a few practical ‘take aways’ in the section on video capture and editing. Finally, prototyping is an important stage of the iterative design process when working with technologies that is often hidden once the final product or performance is produced. In recognition of this, at the end of this resource there will be the possibility to download and test Design Prototypes. Readers with iPhones or iPads can download two Augmented Reality browsers (Argon4 and Wikitude) for free from the AppStore so that two archival Mixed Reality sequences running on the browsers can be tested and compared.

2 Process Notes is a term referring to Kozel’s “Process Phenomenologies” (2015), a phase of the phenomenological process usually existing in the performer’s notes or memory, occupying a transitional space between raw experience and scholarly writing: ‘Phenomenologies are not born whole and complete, they are rather uncooked and messy at first’ (Kozel 2015, 54).

Calling Conspiracy Archives a ‘process archive’ is consistent with the way processes are often archived by dance artists as we work, but it is also an explicit recognition that this work fits into a larger academic research project into archives called Living Archives. Conspiracy Archives developed out of broader explorations into the meaning and practices of somatic archiving and somatic materialism. Somatic archiving is not a pre-existing field into which this research falls, this research acts to constitute the field. While this may sound complex to an early stage researcher, the point is to demonstrate how artistic research at any stage can exist both in wider academic projects or in the professional world. It is also to suggest that work which seems to challenge artistic or scholarly practices may, at the same time, be helping to constitute new artistic or scholarly practices.

Critical Questions: When are you actively fitting into existing research? When are you expanding it? In what ways are you offering challenges or expansions? (Methodological, aesthetic, critical, material, performative?)

1 Margrét Sara Guðjonsdóttir’s work

Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir is an Icelandic-born, Berlin-based choreographer known for her intense and transformative choreographic work that come out of myofascial release techniques and a commitment to the potential for dance to act as a healing force celebrating, and transforming, the broken bodies she sees in the world around her.

The motivation for working with Guðjónsdóttir on an archiving project was the compelling quality of her somatic processes – both choreographically and as bodily practices – and the challenge this deeply internal and immanent work poses for archiving. In particular digital archiving, which tends to capture surfaces, form and dynamics, rather than affective states. Her worked seemed to pose considerable challenges to being captured using digital media technologies.

Critical Questions: Is there something fundamentally conflictual in the work you are drawn to do? Perhaps something that you might at first think is impossible? Is your work an act of celebration and/or resistance?

When working in a complex way there is often a need for description so that your reader knows what the work is like. This sounds very basic but can be challenging. Description might take several forms (written, visual, phenomenological, audio recording, drawing, etc). You might be able to play with how you publish or present these descriptions, or to juxtapose several descriptive perspectives or voices. Guðjónsdóttir offers a particularly relevant example because her work is so immanent, somatic and experiential that it is hard to convey to people who have not attended her performances or workshops. Simply saying ‘You had to be there’ is rarely considered sufficient in an artistic research context, and the argument for not even trying to capture the ephemerality of performance has been rejected in favour of a more nuanced approach to unraveling or unfolding the ephemeral, and to identifying what might remain and how. (Schneider 2011) This section provides a trio of voices to open up Guðjónsdóttir’s work, describing her somatic practices, her artistic processes, and the performance of HYPER (2017–2018).

1.1 Guðjónsdóttir’s voice in written form

Here is an account of Guðjónsdóttir’s work in her own words. This description is in the familiar form of the choreographer’s reflection on her own work, taken from a grant application.

My work is grounded in a practice that brings together the physiological and psychological states of the body with a focus on working and exploring pathologies of the social-political body within our own bodies. Displaying the politics of intimacy is a core theme within my choreographic work. My working methods directly inform the themes of the artistic works I have presented, and extend beyond the limits of professional life and performance-making for those who have participated in the development of the practice with me. The aim of establishing and nurturing a sustainable way of working is to create an environment where both performer and onlooker are able to question their inner and outer realities through it. Over the course of the last eight years, I have been focussing my professional research on the physical doorways into the physiological and emotional sub-worlds associated with myofascial release. In a practice I name Full Drop, I have been able to identify and research numerous reproducible physical processes defined by accessing presence and inner movement. Through this research I have begun the process of mapping out a new category of performative body language, ways of developing it, and transferring the knowledge of it, both practically and theoretically to the wider international dance scene and dance academia.

Once you acknowledge the plasticity of human matter you can recognise healing, or de-conditioning your body memory, as a political act/activism.

Through a framework of nurturing personal and professional connections, deep trust, and long-term commitment with the dancers I work with, I have been able, together with them, to embark on a five-year-long journey weaving through the pathological body and its inner systems. Focusing on de-conditioning more and more of our omnipresent body memory and the cognitive wiring we have developed that is directly associated with it. The practice is based on meditation visualisations, bone work, and development of intensive deep inner listening and surrendering to inner body systems and rhythms. Through the action of letting go of control by entering into an active-passive state of inner listening, we surrender to non-action and create like that a space to witness whatever arises. Without manipulation or judgement in the way we have come to be able to enter into formerly unknown full body states. Opening up our experience to the subconscious and inviting the unconscious to manifest. Creating the circumstances to be ‘undone’.

This new research phase steps from the introspective into the interactive, I will step out of the frame of the personal within the context of Healing as Political, and into a landscape that considers the political nature of our interactions with those forces at play around us and within us, and which maps the extent of that interpenetration and interaction. Through this work, we develop a hypersensibility to and hyper-awareness of the intersection of the inner and outer energetic fields, and how the forces that move us traverse this boundary. My research will aim to encompass the outer and larger tides that move through us, pulling our matter along in their wake. I will explore the lived reality of quantum entanglement, interconnectivity through the plasma of connectivity, connection, and reciprocity, and the nature of the resonance between individuals. It is my aim to make visible and get deeply in touch with the colourful reality of the energetic landscapes we navigate on a daily basis partly or in some cases completely unaware. (Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir 2018)

1.2 Video voices

For the composition of the Mixed Reality installation Conspiracy Archives, we discussed extensively the difference between documentation and archiving. For this project we preferred to regard what we were doing as archiving rather than documentation, because of the greater scope for an archive to be a performance of memory whereby the affective and kinaesthetic qualities of the archival material can endure in the bodies of those who encounter it. People could then take the somatic states of Conspiracy Archives away with them living, even in small ways, inside their bodies in the same way audience members can feel quite transformed when they walk out of one of Guðjónsdóttir’s performances, or participants when they leave one of her workshops. Despite seeming to choose archiving over documentation, there remains a time and a place for basic and informative documentary. Here is a video documentary offering verbal and visual accounts of her work:

Fig. 1 Documentary video of Guðjónsdóttir’s work (2017). Video capture and edit by Jeannette Ginslov

1.3 The voice of a critic

Finally, to complete the trio of voices contributing to a description of Guðjónsdóttir’s work, here is a glimpse of a critical review of her piece HYPER. This was a re-performance of the piece in Stockholm in 2018.

Örjan Abrahamsson the dance critic of the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter astutely observed that the experience of this performance took some time to sink in. He revealed an important temporal dimension of somatic experience when he wrote

Only later, alone on my way home after leaving my company, the magnetic force of the show begins to impress, really felt in the body. Gradually, the intellect can catch up with the intense, physical experience.’ An example of a unique approach to choreography, it requires time for ‘the non-conscious and the brain’s limbic system to communicate the physical body’s reactions to consciousness. When it happens, as in HYPER, the effect is overwhelming. Shocking. long-acting. (Abrahamsson 2018)

Critical Questions: If you include a range of voices in a text, can you think of them as a choreography in themselves? What message or tone do you seek to convey with the voices you draw together? Obviously, citation is important for research but it can be done creatively at the same time as following academic conventions. If you draw different voices together in a thoughtful way you will effectively be expanding the academic ‘canon’.

A ‘take away’ for the reader at the end of this section is that the problem of describing a complex or subtle work can be handled in a variety of ways, and come in a variety of voices. In the following section the Process Notes of two of her close collaborators are presented: Kozel and Ginslov.

2 Process Notes

There is a lot of interest in phenomenology, in particular how to do or to perform phenomenology in the context of research. In previous writing, Kozel has used phenomenology as a method for integrating corporeal experience into scholarly writing and recorded a tutorial on how a phenomenology might be done. (Kozel 2007, 2012, 2013, 2015, 2017, 2018) In “Process Phenomenologies” several examples of note taking from the midst of sensory or affective experience are provided, revealing how notes can occur in structured or unstructured ways – as in a guided workshop or the familiar mad scramble to find something to write on so thoughts and impressions won’t be lost. These notes can be in verbal form, drawings, diagrams, sounds or fragmented words. They are often quite private and unpublished, either because they seem too intimate, raw or confusing. Usually they are simply not deemed appropriate for academic publishing.

Responding to a request by the editors of this ADiE resource for more examples of phenomenological process several are included in this section. Particular emphasis is placed on Process Notes that reveal the transformation of somatic qualities from the point of experience of Guðjónsdóttir’s work to various stages of writing or image production. The notes reflect the complex relationship of being on the receiving end of motion, deeply entangled in the movement of the dancers but not actually being one of the dancers. Kozel’s notes are from the position of being a member of the audience and of witnessing studio processes for the composition of Conspiracy Archives; Ginslov’s are from the perspective of capturing the movement on video and later editing it.

Critical Questions: How are you involved in an exchange of sensations or affects from different positions in the collaborative artistic process? How can you respect your own perspective, and acknowledge its relevance, without letting it dominate the narratives that come from the work of a group?

2.1 Notes from the Theatre

Here is an account of Guðjónsdóttir’s work from the perspective of Kozel’s first encounter with her choreography.

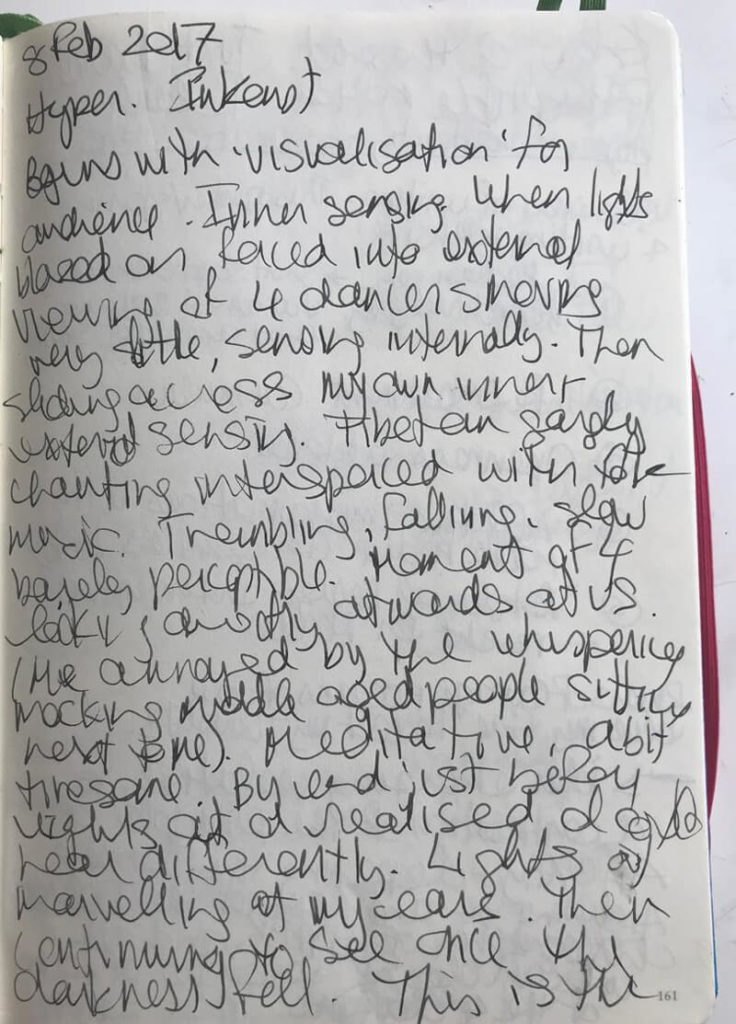

I first encountered Guðjónsdóttir’s work as an audience member, revealing that phenomenological reflection of dancers moving can be done powerfully through one’s own receptive body. Here are my notes. I don’t expect you to be able to decipher my handwriting, but to grasp that it was written hastily. In this instance I decided not to write my reactions in the theatre in the dark because I did not want to disrupt the somatic state I experienced while watching the première of HYPER. These were written in a bar immediately following the performance.

When I reveal notes like this I always feel a bit like I am showing how sausages are made. Something messy, something one is not really supposed to do, but a process that might contain useful material precisely by being so raw or close to experience. This is echoed by the methodological stance of doing a phenomenology of others performing, but filtered through one’s own body. Further, there something a little methodologically risky because of the subjective-objective tensions. I’m not claiming to use my subjective experience to assert the experience of the bodies I witness on stage, nor am I claiming to assess the truth of the somatic experiences; but I experienced enough to make me want to work further with Guðjónsdóttir.

These hasty phenomenological notes made their way into a longer piece of writing for collection on philosophy and performativity. (Kozel 2019) With the deliberate intent to open out a bodily state to a reading audience of philosophers who might not be accustomed to the implementation of phenomenology as a practice, it appears like this:

How did I come to work with her?

I attended the première of Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir’s work Hyper in Malmö at the Inkonst venue in February 2017. It was snowing. I rode my bicycle to the theatre after an intensive day, racing out of a highly discursive few hours into the magic of a snowy evening. Illuminated snowflakes dancing in the street lights.

Hyper was commissioned by one of Sweden’s pre-eminent contemporary ballet companies, the Cullbergbaletten. I had no expectations beyond a sketchy knowledge of The Cullberg Ballet being named after Birgit Cullberg, a radical choreographer of the mid 20th century, and a sense that the company now faced a struggle between keeping the its tradition alive and addressing what might be happening now in the choreographic scene.

The theatre was full. The piece began with the audience members being invited to close their eyes and follow a guided meditation offered by the choreographer. Guðjónsdóttir stood somewhere to the side of the stage – I didn’t see her from where I sat. Her voice was light, with Icelandic inflections. The meditation was a simple internal body scan with the invitation to extend downwards through our tailbones deep into the earth. The result, for me at least, was a greater degree of presence: gathering together all my scattered thoughts and motions of the day into my bodily schema, and a re-patterning of what this schema might be.

Already, I could tell that the audience was divided: some really did not like it.

Four dancers stood on stage, facing the audience, wearing somewhat random casual clothes. One had hiking boots, one shoes, one was barefoot, one wore socks. They began, almost imperceptibly, to move. For some time I have been pursuing, philosophically and physically, questions of affect, somatics and ambiguity and trying to disentangle them. Here I was presented with dancers moving in an ambiguous way: moving but not moving, sensing internally but aware of the audience by looking directly out at times, very slowly shifting not so much their bodies but their bodily states. Aesthetically liminal, as they rippled through states that were beautiful, grotesque, mundane or nothing distinct because they kept shifting. Sensorily liminal, because as an audience member I was not sure what I was experiencing but knew I was being taken somewhere different. Could immanence be performed, actually be staged?

The dramaturgical shifts in the performative infrastructure were as sharp as the shifts in physical and affective movement were slow and stretched. The music alternated between contemporary folk, electronically treated Classical Indian music, and complete silence. There were no fades in or out. The sound transitions were sharp cuts. At the start of the piece the lights did not fade up, they came on in full force, which, when combined with silence, caused the metal of the theatrical spotlights to tick and creak as it expanded with the heat of the powerful bulbs. This quiet sound seemed to be inordinately loud. My hearing was pronounced throughout the piece, resulting in a sense near the end that my auditory passages were cleared of blockage and I could hear directly into the centre of my head. This is a striking thing for me, for I have tinnitus and my hearing is generally fuzzed meaning that external auditory sounds are obscured by sounds that my ears provide.

The sheer and almost perverse banality or oddness (I won’t say absurdity, because this has a specific tradition in theatre and dance) of the movement became a source of fascination and delight. Not so for other members of the audience, because it became clear that many people found the performance quite hard to watch. There was restless shuffling in seats, and some exasperated hand and head gestures implying distaste for the work.

The dancers trembled, tilted, fell to the floor, got up again, and continued with the internal processes that generated this strange choreography – for it was clear that they were following a particular set of somatic processes. The audience too was taken on a somatic journey, one that invited a different quality of attention. If they choose to accept it. I left after this 38 and a half minute piece, knowing I could not take in the different piece programmed after the interval because I knew I had to let the piece settle, respecting the sensory reconfiguration it had produced within me.

Critical Questions: Are there aspects of your process that are rich in themselves and might be useful either for others to know about for their own processes, or that point to concepts or theories that might not be as evident in the final product? Conversely, are there notes that must always remain private?

2.2 Notes from the Studio

Here is an account of Guðjónsdóttir’s work from the perspective of Susan Kozel’s time in the studio with the choreographer and dancers.

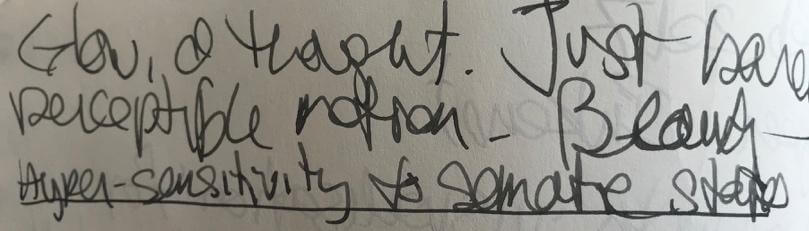

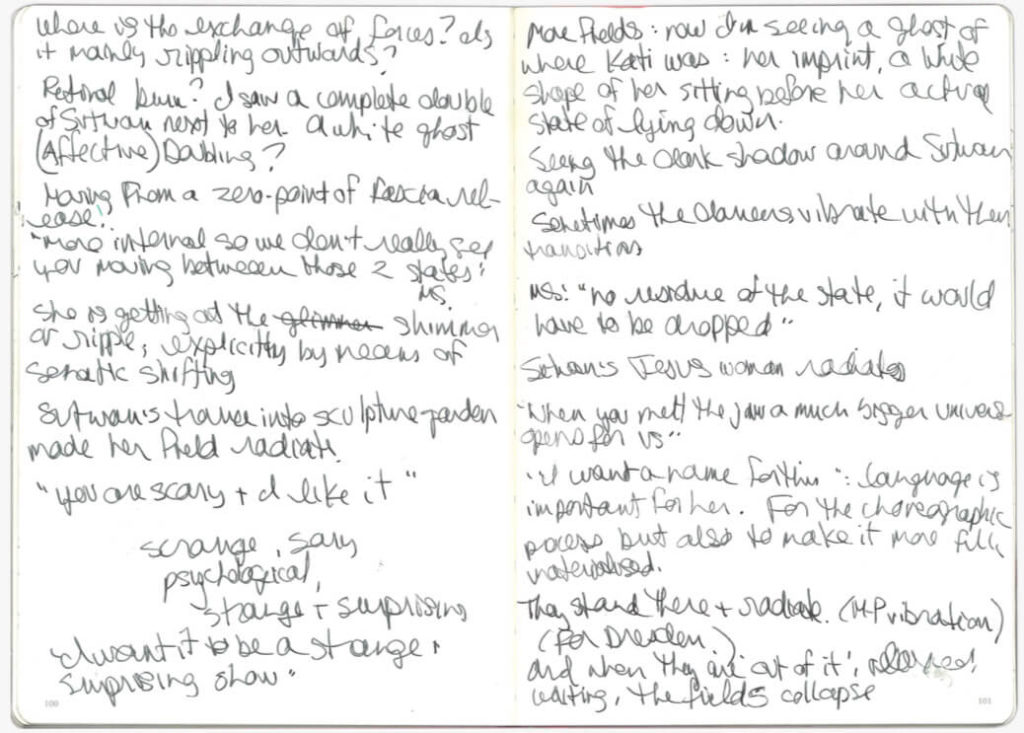

The phenomenological experience of being in the audience was expanded by many hours spent in the studio with Guðjónsdóttir and Ginslov as she devised her new piece, Conspiracy Ceremonies: HYPERSONIC STATES. One particular aspect of these notes is worth opening up here, because it reveals something that has not yet fit into any academic work. It may never make it into a book or an article, but remains a key affective discovery. The point to be made here is that sometimes the research process throws up rich little nuggets that may be circulated in discussion without yet finding a way into the more formal research publications. This, I believe, is fine and reveals that artistic research exists in a range of dialogic modes. Just as we would not want to video all rehearsal processes, particularly when they open up somatic states, we do not necessarily have to write about everything we discover in the studio. Except for special circumstances. Like this one.

What I was trying to grapple with here was a strange perceptual phenomenon that I, at first, thought was my tired eyes malfunctioning.

Retinal burn? I saw a complete double of Sutwan next to her. A white ghost…

More fields: now I’m seeing a ghost of where Kati was: her imprint, a white shape of her, sitting before her actual state of lying down…

I saw bands of white light around the bodies of the dancers. The studio was hot, I was jet lagged and a little ill, so I blinked to make them go away. They persisted and then I realiszed I was seeing a sort of energetic field around the dancers. I noticed that as Guðjónsdóttir directed the dancers to stay in the somatic states she desired for her choreography the fields appeared. (Her directions are the words appearing in quotation in the notes above.) When the dancers became distracted or tried to dance the states in a technical way the fields disappeared.

This is an example of a lived experience, producing phenomenological “data” (if you like to look at things this way) which I have decided not to use in my more formal writing. I have presented it here, and recently at a conference entitled “Energetic Forces as Aesthetic Interventions” where Guðjónsdóttir and I discussed her work.3 Perhaps because it can so easily be misinterpreted as “auras,” in either the 1980s New Age sense or even those according to Walter Benjamin, that I prefer to discuss it in conversation or in process discussions. This material is entirely consistent with work in somatic materialism, but would need a particular style of writing and a lot of cross-referencing for me to be comfortable with how it appeared in most scholarly research contexts.

3 Curated by Sabine Huschka at the HZT (Hochschulübergreifendes Zentrum Tanz) in Berlin. A publication of all contributions is anticipated.

Critical Questions: Do you have a secret file of experiential knowledge that awaits the right moment and the appropriate place for it to be revealed? Instead of burying it as “unscientific,”, revisit it from time to time to let its significance either grow or fade away. Are there moments that are surprising or even risky? Be aware of any implicit or explicit ethics in revealing your experiences or the experiences of others.

2.3 Notes from the Visual Capture Process

Here is an account of Guðjónsdóttir’s work from the perspective of Jeannette Ginslov using a video camera to capture material for archiving.

My role in Conspiracy Archives, is to mediate, extrude, archive and amplify the affective hyperstates of the live performers, with video camera and editing processes, for transference to future audiences engaged in an AR interaction design.

My methodology is a post-phenomenological one, as I experientially engage with the technology and participate within the archiving process through the praxes of mediation rather than documentation. (Ihde 1993, Rosenberger and Verbeek 2015) Furthermore I have extended the notion of mediation to one of extrusion. Extrusions are defined as the movement or emission of lava through a volcanic crater onto the earth’s crust or the forcing of heated aluminium through a dye or precast form, transforming it into a specified shape. It is a metaphor to describe how I use the camera to gather the vibrant vital forces emanating from the dancers and the edit to reveal what Jane Bennett calls ‘vital materialities that flow through and around us’ (Bennett 2010 pX).

Documentation on the other hand implies an objectifying fixed distance of the camera, capturing or ‘shooting’ shapes and movements in a flat space/time dynamic. With documentation one attempts to capture and define a linear narrative of the time spent in rehearsals and performances, where the camera is usually mounted on a tripod at the back of the studio or theatre. Here the liminal states emanating from the dancer are lost to the technological camera eye.

Mediation and/or extrusion in this project, however, are ways of doing, a post-phenomenological process for the construction of an archive. Used experientially, the technologies transfer the affective gestures, shifts and micro movements or stillness of the dancers into the timeline and ultimately the AR/MR interactions. During the mediation process the camera in my hands becomes an extrusion of my ocular, felt and proprioceptive senses. It becomes a lived technological extrusion: an entwinement of bodies, technology and the lived environment. Here an inter-corporeality of technology the dancer and the videographer is necessary where the experience of my archiving process merges with that of the dancers. My strategy attempts to replace and return visuality to a more perceptual dimension.

The first ‘take away’ from such a nuanced process is that to mediate movement, rather than simply document it, it is desirable to have a deeper understanding of the movement practices. This can be achieved in a variety of ways, but emphasis is placed on the experiential: time devoted to seeing the work in the theatre and in the studio, during rehearsals warm ups and rehearsal discussions. In the case of working with Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir this meant understanding practice of Full Drop as well as the phenomenon of hyperstates. Practicing Full Drop provided an insight to the interior landscape that the hyperstates explore, where there was an entwining of self, body, environment, emotions and the felt senses. The goal is, as much as possible, to develop a kinaesthetic consciousness that can help to shape the way movement is mediated by the technologies.

In order for the transference of affect to flow from dancer, to camera, to me, to the edit, to the AR and finally to the viewer in the installation, I had to make some choices. The camera and edit needed to become experiential and transparent. I intuitively changed settings on my camera to accommodate changes in lighting or sound. I also made the choice of not making a storyboard, a traditional method of screendance. This project required another method of storytelling. When the extrusion is improvised the story unfolds into you and you merely listen. Movements become wavelike, and it is possible to just listen with the entire body.

Before the extrusion however, I thought about the framing of the dancers and decided to keep the dancers mostly in the centre of the frame and to not change the frame size too much for each dancer’s sequence. Obviously, I also had to get different angles of the dancers on different days to cover for times when for example, the dancer was not performing their best or I might need another point of view of the sequence.

The second ‘take away’ is to be aware of how much can be captured without technological interventions (like effects, zooms or camera shifts). The main priority in camera capture was to allow the hyperstate to flow into the mediation process, without too much technological intervention and disturbance. All changes had to become transparent so that the flow was not interrupted with, for example, changes from a wide shot to a close-up.

The framing had to become an instinctive affordance for me, extending the idea of kinaesthetic consciousness, framing with my felt senses rather than intellectual decisions. I made changes in frame size by feeling the affect from the dancer, pouring into the lens and so into me. This became my guide. If on a tripod, I zoomed in and held the camera steady to let the waves of affect engulf me. If the dancer moved out of the frame, I remained calm and did not chase her with the camera. I paused a little, then zoomed out to create another frame size, or I just kept it still in case she entered the frame again. As a screendance maker, exits and entry points, a variety of angles and frames sizes are important for the editing process, however here, I had to let that training go. I even tried placing my hand on the camera whilst on a tripod, without having the anti-shake setting on, to see if my heart beat could affect the media.

One technique I used was to set the camera on wide with autofocus, and to step into the what I called the ‘mediasphere’ that contained the dancer, camera and me, where I am very close to the dancer – approximately 30 centimetres – with a hand-held camera. One of the dancers, Laura Siegmund, on the first day of rehearsals was so disturbed by this intrusion that, even with eyes closed, she stopped and got up to start again in another part of the studio. We had become entangled in each other’s powerful vibrational forces of affect and extrusion. Eventually she became accustomed to my camera and presence: we had become transparent to her.

A third ‘take away’ from this experimental camera technique is to be sensitive to possible intrusion, or breaks in trust and flow between the dancer, camera person and camera. Trust can be built up over time, but the camera person has to be willing to adapt and change instead of imposing a technique or a presence.

I also sometimes wondered when or if ever the dancers were performing for the camera in the beginning, pushing sometimes too hard physically instead of allowing for the affect to flow from their bodies. Guðjónsdóttir at one time during the rehearsals asked dancer Suet-Wan Tsang not to roll her eyes too far back in her eye sockets but to allow the sensation of that moment, to be evoked in her body. Whilst this is great footage for a screendance maker, it became a literal event, a representation of her inner state. We all had to mediate in much more sensitive and intimate ways.

My camera was so close it did not need events to extrude the affective states, and even if on a tripod in a mid-range shot, the affect streamed through to me with the dancer projecting emotional forces or states of physical ecstasy and tension.

Critical questions: What is the video camera to you? What relation does it have with the person behind the camera and with the dancers? What choices do you make even before you pick up the camera? What body state to you inhabit when you use the camera? How much of this is decided in advance and how much happens intuitively in the flow of capture?

2.4 Notes from the Visual Editing Process

Here is an account of Guðjónsdóttir’s work from the perspective of Jeannette Ginslov, opening up the processes for visual editing.

The amplification of tension and emotion usually takes place in the edit. Traditionally one refines this with decisions about rhythm, timing, frame size, colour or repetition for example. However, with this extrusion I merely had to focus on pulling the most affective clips onto the timeline. This was not such a difficult task as the dancers had already started the process of amplification with their hyperstates to such an extent that I had difficulty in selecting just a few.

The speed of their hyperstate performances were very slow, and this timing needed to be reflected in the edit choices. The clips had to be as stable as possible without too many cuts to avoid severing the affective flow from dancer to viewer. There were times that I needed to use another angle or frame size to cover bad performances or camera interferences. Overall, the edit had to become transparent to further the methodology of affective mediation and extrusion.

A ‘take away’ relating to using video to act as an affective exchange between dancer and viewer is to take care not to tamper with an affective flow that begins in physical space, travels through the camera and ends in the display format for the audience. This sometimes means resisting the standard idea of a beautiful shot from a formalist or aesthetic perspective.

The Process Notes in the sections contributed by Jeannette Ginslov relate to her phenomenological adaptations of her repertoire of visual skills. They are not meant to be read as the correct way to capture or edit affect visually, but to reveal her working methods as she experiments with capturing and conveying affect. Once again, it is evident that when working with complex material description plays a crucial role, in language and in visuals, so that the artist herself can fully register what is happening and find a way to open this out to other interested practitioners.

3 Design Prototyping

The final section of this phenomenologically grounded process archive offers Design Prototypes. This section continues both the themes of Critical Questions and Process Notes, acknowledging that when complex and collaborative work is discussed there is a need for detailed description in order to begin to understand it, and to convey the experience to others. The technological prototypes prepared by Keith Lim are in themselves Process Notes, and can be found below.

This artistic collaboration has several motivations for working with Augmented Reality/Mixed Reality (AR/MR) technologies. We wanted to intervene in this burgeoning field with work that respects the nuance and ambiguity of corporeal presence, and possibly transfers some of the body states to future audiences, or witnesses, of the material in digital format. Aspects of archival preservation entered, but for us it was not in the spirit of reproduction or documentation, rather in the continuation of affective exchanges. We believe that careful use of Mixed Reality technologies and techniques might produce a living archive for the somatic states of Gudjonsdottir’s choreography. A further motivation is to continue the collaboration between Ginslov and Kozel in using AR/MR technologies in the field of affect and performance. (Kozel 2012)

Critical Question: Why use technology/technologies in your research?

Currently we are experimenting with two different AR browsers. We are trying to balance aesthetics with access, and tourability with longevity. Aesthetic concerns point to the visual material needing a certain look and feel for the transference of affective qualities, and to be faithful to Guðjónsdóttir’s process for developing Conspiracy Ceremony – HYPERSONIC STATES. A concern for access means that we want the technology used to create our work to be free, and fairly easy to operate on most people’s mobile phones or tablet devices. Tourability, for us, refers to its visual appeal as a gallery installation and its ease of being set up and maintained by gallery staff after it has been set up and we are no longer there to host it. (Unlike a performance, it needs to be standalone.) Longevity takes in the length of time it is likely to work on existing hardware and software platforms, so that it can tour without having to be reprogrammed and upgraded every six months. This has budget implications for the artistic production, but also implicit are archival concerns. How long might this archive of Guðjónsdóttir’s work be alive given the state of flux that characterises the tech industry?

When working with any technology, it is important to bear in mind that the tech industry has a vested interest in making everything seem more fluid, easy and problem-free than it really is. Be aware that you will be working with an industry that upgrades so fast it cannot keep up with itself. The marketing rhetoric is designed to sell products, not necessarily to give you an honest account of what a product or system can do. And the most difficult thing is to assess for how long any particular configuration of device, software and networking protocols will last. There are often hidden costs, and there is the App Store, with its complex and time-consuming gate-keeping and updating procedures. This is not to scare you off, but to help you realise that if everything seems more complicated, slow and precarious to develop this is not your fault. It is because the reality of working with the media technologies does not coincide with the affective rhetoric permeating our digitised society at present. Even experienced artistic researchers wrangle with these issues at all times.

It can be helpful to regard the prototyping process in terms of composition or choreography. All are fundamentally based on repetition. Designers call this iteration, performers and choreographers might call it rehearsals. Conspiracy Archives exists at the moment in two simultaneous prototypes, running on two separate web based AR browsers: Argon and Wikitude. They are both currently free. Argon only works on iPhone and iPad, Wikitude works on Apple and Android.

Critical Questions: Why use technology/technologies in your research? Which platform, app or software/hardware configuration will you choose? And can you test more than one in the process of developing your piece? If one does not work out, do you keep trying to solve the problem or abandon one technological solution to try another? (This is often necessary but has implications for time and funding.)

Download and test the prototypes for the final glimpse of Process Notes, as prototypes in process.

Argon:

(Note: in the 6 months between the first prototype exhibition and the publication of this resource the Argon developers changed the platform and our prototype is now broken. We have left it in this resource to highlight, once again, the problem of longevity when working with technologies.)

- Download Argon from the app store.

- Open the app. In the top bar like any web browser there is a space to enter a URL

- Enter this url for our prototype channel somatic.livingarchives.org

- Point your phone or iPad at the images below (one at a time). Their associated video sequence should appear. If it does not work immediately, check your network access and adjust the distance between the tag and your phone. Depending on how fast your wifi connection is you might have to wait a little.

Wikitude:

- Download Wikitude from the app store.

- Open the app. In the top bar there is a space asking you to enter a search term or code: type in Conspiracy Archives. This option will appear in a list as with any web search. Select it.

- Point your phone or iPad at the images below (one at a time). Their associated video sequence should appear. If it does not work immediately, check your network access and adjust the distance between the tag and your phone. Depending on how fast your wifi connection is you might have to wait a little.

With both Argon and Wikitude, you can print out the tags or use your computer’s display. Our intention is for them to be quite large and installed in a gallery space, this might account for any peculiarities in the size of the dancer in the video in relation to the size of the dancer in the text.

The Critical Questions, Process Notes and Design Prototypes in this resource are practical ways of opening out the artistic research project Conspiracy Archives. This research has a performative component, a philosophical component and a digital design component, but all of these can be seen as ways of relating to Guðjónsdóttir’s work, and they are opened up through various voices and descriptive modes. The looping formulation of calling this ‘a process archive of an archival process’ is not just word play: this resource is, in itself, a digital archive. By spending time with the material, your body and thoughts carry forth this archive; and by downloading the prototype tags you have a piece of it in digital as well as somatic format. For however long these may last.

Acknowledgements

We thank the dancers: Johanna Chemnitz, Catherine Jodoin, Laura Siegmund, Marie Topp, Suet-Wan Tsang and composer Peter Rehberg. Thanks also to Daniel Spikol, the School of Arts and Communication at Malmö University and the Living Archives project supported by the Swedish National Research Council.

Notes

- msgudjonsdottir.com/conspiracy-ceremony-hypersonic-states Dancers: Johanna Chemnitz, Catherine Jodoin, Laura Siegmund, Marie Topp, Suet-Wan Tsang. Music composition: Peter Rehberg.

- Process Notes is a term referring to Kozel’s “Process Phenomenologies” (2015), a phase of the phenomenological process usually existing in the performer’s notes or memory, occupying a transitional space between raw experience and scholarly writing: ‘Phenomenologies are not born whole and complete, they are rather uncooked and messy at first’ (Kozel 2015, 54).

- Curated by Sabine Huschka at the HZT (Hochschulübergreifendes Zentrum Tanz) in Berlin. See forthcoming publication Huschka and Gronau 2019. A publication of all contributions is anticipated.

Reference List and Additional Resources

Margret Sara Gudjonsdottir’s site msgudjonsdottir.com

Jeannette Ginslov’s site www.jginslov.com

Living Archives Research Project (Malmö University) livingarchives.mah.se

Abrahamsson, Örjan. 2018. “Scenrecension: Cullbergbalettens ‘Hyper’ är mångtydig och imponerande.” In Dagens Nyheter, Stockholm, 2018.03.01. www.dn.se/kultur-noje/scenrecensioner/scenrecension-cullbergbalettens-hyper-ar-mangtydig-och-imponerande/?print=true)

Bennett, Jane. 2010. Vibrant Matter. Duke University Press: Durham and London.

Huschka, Sabine and Barbara Gronau. 2019. Energetic Forces as Aesthetic Interventions. Politics of Bodily Scenarios. Bielefeld: transcript.

Ihde, Don. 1993. Postphenomenology: Essays in the Postmodern Context. Northwestern University Press: Illinois.

Kozel, Susan. 2019. “Performing Phenomenology: The Work of Choreographer Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir.” In Phenomenology as Performative Exercise, edited by Lucilla Guidi and Thomas Rentsch, for the Studies in Contemporary Phenomenology series. Brill Publishers.

Kozel, Susan, Ruth Gibson and Bruno Martelli. 2018. “The Weird Giggle: Attending to Affect in Virtual Reality.” Transformations, Journal of Media, Culture and Technology, Special Issue on Technoaffect: Bodies, Machines, Media: Issue 31. www.transformationsjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Trans31_01_kozel.pdf

Kozel, Susan. 2017. “Performing Encryption.” In Performing the Digital, edited by Martina Leeker et al., 117–134. Bielefeld: transcript.

Kozel, Susan. 2015. “Process Phenomenologies.” In Modes of Embodiment: The Poetics of Phenomenology in Performance Studies, edited by E. Nedelkopoulou, Jon Foley Sherman, and Maaike Bleeker, 55–74. London and New York: Routledge.

Kozel, Susan. 2013. “Video tutorial on Phenomenology for the Practice Based Research in the Arts Course.” Stanford University. www.youtube.com/watch?v=mv7Vp3NPKw4

Kozel, Susan. 2012. “AffeXity: Performing Affect using Augmented Reality”. In Fibreculture Journal, Issue 21 on “Exploring affect in interaction design, interaction-based art and digital art”, edited by Jonas Fritsch, Thomas Markussen, and Andrew Murphie. twentyone.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-150-affexity-performing-affect-with-augmented-reality

Kozel, Susan. 2007. Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology. The MIT Press.

Rosenberger, Robert, and Peter-Paul Verbeek (eds.). 2015. “A field Guide to Postphenomenology.” In Postphenomenological Investigations: Essays on Human–Technology Relations – Essays on human-technology Relations, 9–41. London: Lexington Books.

Schneider, Rebecca. 2011. Performing Remains. London and New York: Routledge.

Susan Kozel

Susan Kozel is known for artistic and philosophical work applying phenomenology to a range of sensory, affective and somatic practices. For the past two decades she has worked at the convergence between dance, philosophy and digital technologies. She is a Professor with the School of Art and Communication at Malmö University, directed the Living Archives Research Project funded by the Swedish National Research Council (livingarchives.mah.se) and is now establishing a research network called Live Theory. Her publications include the monograph Closer: Performance, Technologies, Phenomenology (MIT Press, 2007) and many shorter pieces (susankozel.com).

Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir

Margrét Sara Guðjónsdóttir is an Icelandic choreographer living and working in Berlin (msgudjonsdottir.com). She has created and toured internationally her performance work since 2010. Displaying the politics of intimacy and exploring pathologies of the social political body are core themes within her choreographic work. In 2013 her work started taking shape from her on going in-depth research into a methodology that accesses physiological and emotional sub-worlds. She has developed a new genre of performative body language, and an original working method that directly informs her creative outcomes. She began her on going collaboration on somatic archiving with Susan Kozel in 2017.

Jeannette Ginslov

Jeannette Ginslov is a specialist in digital dance for AR and Screen. She has an MSc Media Arts & Imaging – Screendance from Dundee University Scotland (Distinction) and an MA in Choreography, Rhodes University South Africa. Currently she is a Creative Technologies PhD Candidate, with a Scholarship from the Applied Science and Arts & Media Departments at London South Bank University researching Guðjónsdóttir’s Full Drop, a meditative dance practice, within a variable ecology of biosensor, digital dance and data visualisation technologies. She is Director & Founder of Screendance Africa (Pty) Ltd.

Keith Lim

Keith Lim is a Jack of All Trades, Master of Solo / Dance / Authorship (HZT, Berlin). His work bridges performance art, dance, DIY technology and somatic practices: resulting in award winning physical theatre, interactive festival installations and immersive game art (zombiesurvival.academy, www.kidsthesedays.com.au)