How to write (about) piano music that might have come to an end?

Since 2018, we have been conducting an artistic research that aims to research sound production techniques of piano in the 21st century. We have been inspired by words of K.Stockhausen who declared, in 1992, that “piano music has come to an end and something quite different is coming… With the claviers made up to this time, there is nothing new to discover anymore.” The research resulted into a piece composed by a composer Eka Chabashvili in interaction with pianists Nino Jvania and Tamar Zhvania for two pianos, modified piano, video-installations and the virtual piano orchestra. The main aim of the piece Has Piano Music Come to an End? is to contradict Stockhausen and demonstrate various new possibilities of engaging acoustic piano in contemporary music. The piece reflects the most important achievements of piano music history and presents one of instrument’s future perspectives – the modified piano developed within the project. The process aiming to bring piano closer to some principles of contemporary musical thinking resulted into changes in tuning system and mechanism of the upright piano. The aleatoric techniques employed by Chabashvili enables us to demonstrate particular aspects of research presenting fragments of the piece. As we all have musicological background, it took us a lot of effort to avoid inclination towards scientific writing and choose appropriate media and formats to present the results of our research. The vision statement of CARPA7 inspired us to offer to you an experiment: we will present particular research results performing fragments of the piece and demonstrating various artistic types of writing (music, video-installations, literary texts, etc.) and later offer to listeners the verbal explanation of the same ideas formulated in scientific writing style. We will also encourage audience to interact with us and help us to answer the question – are artistic forms of writing able to precisely convey the research concept and conclusions?

Introduction

Since 2018, we have been conducting an artistic research that aims to research sound production techniques of piano in the 21st century. We have been inspired by the words of a German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928–2007) who declared in 1992 that “piano music has come to an end and something quite different is coming… With the claviers made up to this time, there is nothing new to discover anymore.” (Stockhausen 1993, 138) The research resulted into a piece composed by a composer Eka Chabashvili in interaction with pianists Nino Jvania and Tamar Zhvania for 2 pianos, modified piano, video-installations, chamber and virtual piano orchestras. The main aim of the piece “Has Piano Music Come to an End?” is to contradict Stockhausen and to demonstrate various new possibilities of engaging acoustic piano in contemporary music. The piece reflects the most important achievements of piano music history and presents one of the instrument’s future perspectives – the modified piano MODEKAL developed within the project. The process aiming to bring piano closer to some principles of contemporary musical thinking resulted in changes in tuning system and mechanism of the upright piano.

As we all have a musicological background, it took us a lot of effort to avoid inclination towards scientific writing and to choose appropriate media and formats to present the results of our research. The vision statement of CARPA7 motivating artistic researchers “to creatively utilise, challenge and supplement words and written texts, and to integrate reflective appraisal into artworks themselves” (CARPA7 6 November 2021) inspired us to offer to our colleagues an experiment: we introduced particular research results presenting a video-recording of the piece[1] and later offered to CARPA7 participants the verbal explanation of the same ideas formulated in scientific writing style. We also encouraged the audience to help us to answer the question – are artistic forms of writing able to precisely convey the research concept and conclusions?

- [1]This particular recording is one version of the piece that represents aleatoric music.

Now we encourage our readers to do the same.

How to write (about) piano music that might have come to an end? Version 1, video on Youtube.

In the given recording we present our research results using artistic forms of writing. Let us do the same based on academic forms of writing.

How to write about piano music that might have come to an end? Version 2

Has piano music really come to an end? To answer this question, we – a composer and two pianists – decided to conduct artistic research. In order to reveal the future perspectives of piano, we had to analyse the history of piano and piano music.

We consider the history of piano music as a cycle consisting of several lives. Life, according to Eka Chabashvili, is a time-bound phenomenon, representing one of many phases of existence and it is constantly changing in multiple time and spatial dimensions. In her opinion, each life consists of invisible gravitational waves that pass through one phase of time and space and then disappear. Then new waves arise, creating a new phase of existence and a new life emerges. Thus, eternity is a sequence of those phases. The transitional period between the phases is the Apocalypse. The Apocalypse is a kind of the end of gravity, the longing for the end and the beginning of a new phase. Thus, Stockhausen’s announcement could be connected with the Idea of Apocalypse and “longing” for it. Actually, Chabashvili interprets some scientific theories (in this case – the theory of gravitational waves) liberally – as an artistic Idea that serves as a foundation of the construction of the work.

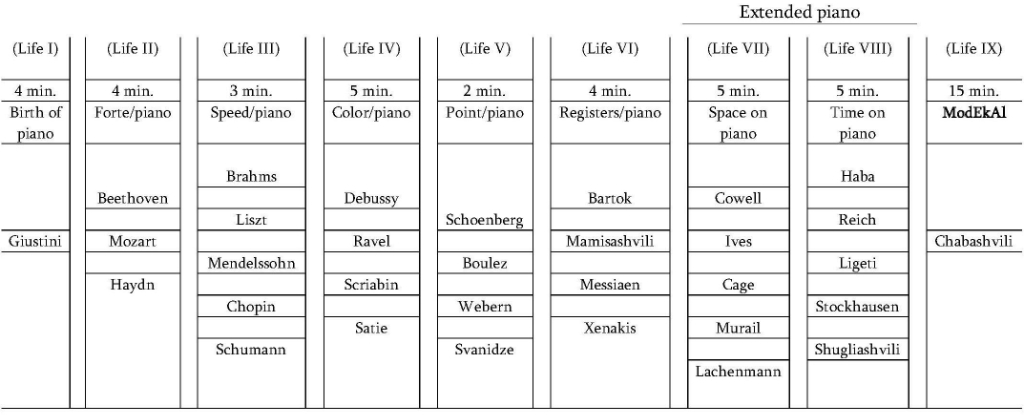

Based on Chabashvili’s idea, we divided the whole history of piano music into 9 lives represented by 32 composers who, according to us, influenced the development of the piano music genre.[2] Interestingly the lives do not always follow exactly the chronological order.

- [2] We included among those composers several Georgian composers too. They might not have influenced the development of art music worldwide, but they demonstrate how the spirit of the epoch penetrates all national schools, despite various obstacles – in our case, the discriminating policy of the Soviet regime that has forbidden progressive art for decades.

How do we justify this categorisation?

The piano and its sound are generally known to be a result of a reconsideration of the priorities taking place in the 18th century art. Against the background of global subjectivization of art, as the inner life of an individual – a subject – gradually became a central theme in art, and in music particularly, the spirit of the new epoch demanded rather spontaneous reflection of emotions. The necessity to express flexible emotions created a need for a new instrument producing more dynamic and flexible sound than a harpsichord – the leading keyboard instrument of the preceding era. This idea was so topical, that three masters almost at the same time created keyboard instruments employing innovative sound-production mechanisms. Though, Bartolomeo Cristofori is regarded as an inventor of the piano, the Florentine master had two competitors for the name of the new instrument’s creator – French Jean Marius and German Christoph Gottlieb Schröter. Thus, the idea of the piano was in the air and it materialized.[3]

- [3] Materialization of the idea is depicted in the first part, or stage (as we call it) of the piece. The stage consists of eight movements, resembling the process of the materialization and creation of the Universe. Again, Chabashvili interprets the theories explaining Universe creation in an artistic way. At the same time, interestingly, she uses unconventional, let’s say contemporary piano sonorities, produced through unconventional, rather modern piano technique, to describe the birth of the instrument back on the edge of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In 171 I, Italian journalist Scipione Maffei, published an article about Cristofori’s new instrument he saw in the Tuscany court, supporting the need for it:

Everyone who enjoys music knows that one of the principal sources from which those skilled in this art derive the secret of especially delighting their listener is the alternation of soft and loud. This may come either in a theme and its response, or it may be when the tone is artfully allowed to diminish little by little, and then at one stroke made to return to full vigour… Now of all this diversity and variation of tone, in which the bowed instruments excel among all others, the harpsichord is entirely deprived, and one might have considered it the vainest of fancies to propose constructing one in such a manner as to have this gift… The bringing out of greater or lesser degree of sound depends upon the varying force with which the keys are pressed by the player; [and] by regulating this, may not only loud and soft be heard, but also gradations and diversity of sounds, as if it were a violoncello.

(Loesser 1990, 6)

Bartolomeo Cristofori died in 1731. One year later, an Italian composer Lodovico Giustini composed 12 Sonate de cimbalo di piano e forte detto volgarmente di martelletti (12 Sonatas for keyboard with loud and soft, popularly called with hammers) that arepresumablythe earliest pieces composed exclusivelyfor a new instrument, known now as a piano (Life I – Birth of Piano). Although the harpsichord still retained its place for some years, step by step it was replaced by the new instrument that has dominated the music world for the next two centuries, starting from Classicism that intensively exploited the idea of the alternation of soft and loud – forte and piano (Life II – Forte/piano).

New epoch with its permanently transforming aesthetical principles set new challenges to the piano and its sound. As a result, Cristofori’s piano has been undergoing multiple transformations in structure and mechanism for centuries. Both aesthetical principles and transformations were directly reflected in music composed for the instrument. For instance, the invention of the “double escapement” by Sebastian Erard in 1821 was of great significance. The repetition lever in these “double escapement” actions allows notes to be repeated more easily and quickly than in single actions. As a result, composers incorporated in music passages performed at very high speed, consequently challenging virtuoso playing (Life III – Speed/piano). Virtuoso playing – became an inseparable part of the image of Romanticism that was about self-expression, particularly through an artist’s self-expression.

In the beginning of the 20th century, the interest of composers shifted towards the notion of colour, or timbre. Nolan Gasser writes that:

It was especially this generation [of composers] that opened up timbre as a first-tier parameter, to be exploited and pursued in its own right. In orchestral works… unusual usage or combinations of instruments, particularly at soft dynamic levels, are a common feature and give the works a distinctly “colouristic” sound… Even in works for solo piano – such as Debussy’s Preludes – new timbres are explored via extremes of register, as well as by unique and “colourful” approaches to harmony and melody.”

(Gasser 1994–2022) (Life IV – Colour/piano)

Exploration of registers continued into the second half of the 20th century leading to discoveries of new piano sonorities (Life VI – Registers/piano).

With serialism came new leading principle defining the essence of music. The serialism is a method of composing using a series of pitches, rhythms, dynamics, timbres or other musical elements. The result is music based on a single structural idea, music as a totally organized order. Order, a symbol of the Universalism and Perfection, exists beyond the music, and the ideal serial music should manifest this perfect order as exactly as possible. Music is considered as “a model of the universal >global< structure” (Stockhausen 1963, 47). Consequently, in this kind of music different elements are subordinated to common principles of organization; sound parameters, among others. In totally structured music raises the question of organizing the sound, its inner world. For serialists sound is a combination of four independent parameters – pitch, duration, dynamics (intensity) and timbre that could be organized. Thus, sound is no more the pre-formed material, it has to be composed as a system of interrelated sound parameters. That brings us to stronger individualizing of separate tones, “pointillism” or “point music” (Life V – Point/piano).

The parameters themselves could be understood as different types of motion of vibrations taking place in a given time, consequently – as different manifestations of time. According to Stockhausen, not only rhythmic events are involved in the organization of musical time, but also pitch (because pitch is the frequency of oscillating movements) and timbre (as a complex of overtones – the frequencies). Simply pitch and timbre are micro-temporal manifestations that the ear cannot perceive as temporal categories (when we hear a pitch, we do not perceive the number of oscillations produced in the shortest distance of time). But it is a temporal category. Consequently, musical composition could be perceived as the unity of several temporal layers in which time flows differently – at different tempi (See op. cit.). This idea interpreted liberally resulted into piano pieces where left and right hands play in different tempi, or where so called variable groups (groups of small notes, grace notes) create another time layer which exists within the basic time structure, without violating its rules, but being at the same time quite independent and very flexible at the same time (Life VIII – Time on piano).

Along with the individualization of separate tones, the new epoch brought quite radical re-evaluation of the concept of the musical sound that resulted into integration of all kinds of sounds and noises in music. The separate sound becomes the separate world, the whole space, inspiring composers to invent new techniques of sound production that would enable acoustic instruments to produce those new sounds – appropriate to new aesthetics. Piano is not an exception. On the contrary it was this instrument that inspired several generations of composers to invent various types of extended technique, be it prepared piano by John Cage, string piano by Henry Cowell or quarter-tone piano by Alois Haba (Life VII – Space on piano).

Thus, for centuries composers along with piano masters have been enriching the sound production abilities of the piano, modifying the mechanism of the instrument, as well as performance technique. It is quite difficult to imagine what kind of innovations the acoustic piano could present to listeners, even in the case of employing electronic technologies. Has piano music really come to an end? Our answer to this question is a modified instrument MODEKAL developed in the framework of our artistic research project (Life IX – MODEKAL).

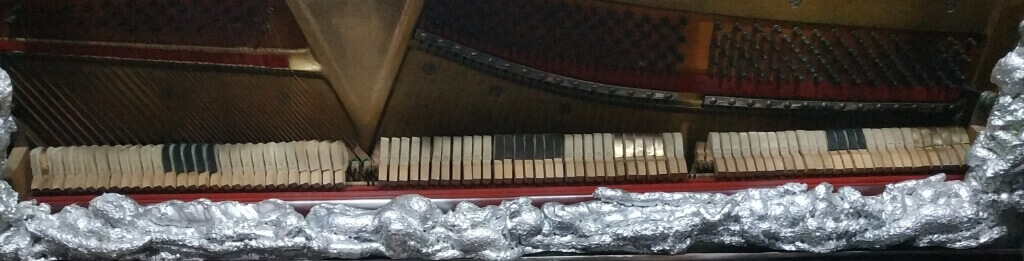

The upright piano “Zarya” was modified according to Eka Chabashvili’s scheme which was enriched with some ideas of piano master Alexander Zirakashvili. The name of the instrument derives from a combination of the names of its creators – “Piano Modified by Eka and Alexander”.

The main goal during the piano modification process was to combine the cultural memory archived in the instrument with the principles of the 21st century musical thinking.

Consequently, instrument creators aimed:

- 1to maintain the basic principle of operation of the instrument’s mechanism – to produce the sound by hitting a hammer on strings and employing the pedals.

- to maintain the traditional form of the instrument’s sound production – to play the keys.

During the modification, the focus was set on timbre that, according to Eka Chabashvili, is the most important sound parameter for expressing a musical thought in contemporary professional music. She also believes that it enriches the abilities of any instrument to influence musical time and space. The piano has been modified on the basis of accumulated information and experience in the field of extended piano techniques of the 20th century. Modekal creators hope to offer to the 21st century composers and listeners a version of piano that is oriented towards the innovative performance methods developed by various authors over the last century, thus bringing the instrument closer to musical thinking of our epoch.

Thus, the main aims of piano modification were:

- to develop new means of sound production:

- to expand the range of piano timbre;

- to modify the tuning system of piano that is based on equal temperament;

- to create a more comfortable environment for the production of the sound of the 21st century piano music by taking into consideration advanced piano performance techniques developed by composers in the 20th and 21st centuries.

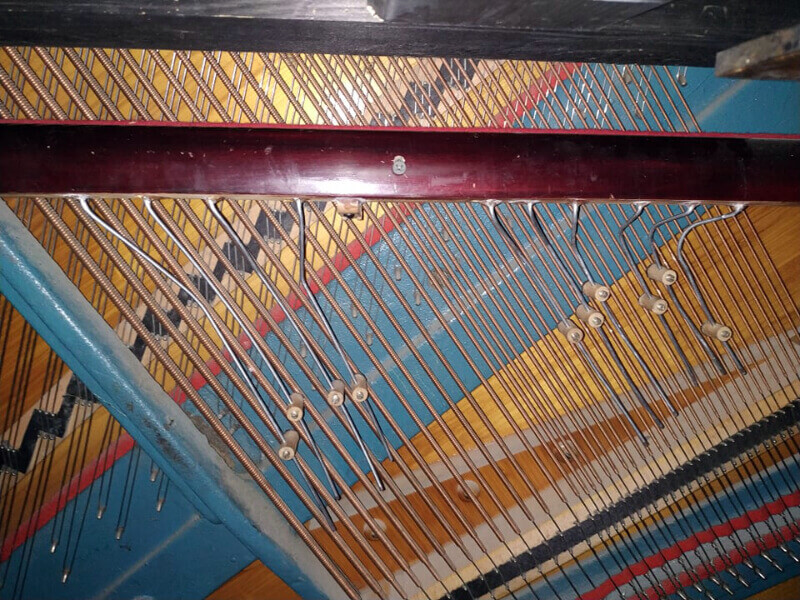

The following changes were made while modifying the instrument:

- Various materials were attached to hammer heads (some heads were left untouched – covered with felt and others were covered with wood, metal, rubber and cardboard);

- New pedal was added with the function of partial opening of the pedals (herewith, instrument creators restored the idea of the John Broadwood and Sons’ piano pedals of the 18th and 19th centuries);

- New mechanism was added for production of overtones in the lower register to be produced by the added pedal;

- A harp string was attached to the instrument’s body in front of the keyboard to be either plucked or played with a violin or cello bow;

- The instrument’s body was also changed for the convenience of playing in the strings – the wood–covered part of the modified piano body was cut out;

- The strings were tuned according to the atomic-nuclear music system[4];

- As a result of changing the tuning system, for orientation when playing the keys were painted in different colours[5].

- [4] The atomic-nuclear musical system was invented by Eka Chabashvili. The aim of this system is to organise pitches in such a way that they associatively resemble the structure of an atom with electrons “moving” through acoustic points in different trajectories around the nucleus. The fundament of this system is the so-called enriched tone representing the central pitch (nucleus) that is surrounded by several microtones (electrons). The modified piano contains seven atoms in various registers; the centre of atoms is painted in red (nucleus) and surrounding electrons are painted in white.

- [5] Op. cit. Outside of atoms, key colours indicate material used to cover hummers that determines the character of the timbre. Yellow keys are associated with wooden hammer heads, blue with metal, brown with leather black with rubber, and beige with cardboard.

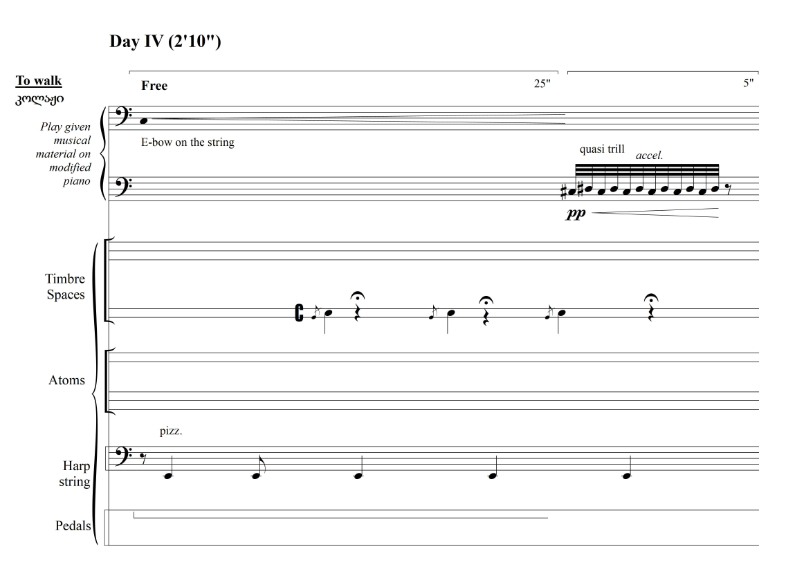

All of the changes mentioned above affected notation: Eka Chabashvili invented a new notation system.[6]

- [6] Music composed for Modekal could be written down using traditional notation, though pitch symbols would not correspond to actual pitches.

The piece composed within our artistic research reflects upon these ideas. It consists of three stages:

- I Stage – Birth of Piano, or Materialization of the Idea

- II Stage – 7 Lives of Piano

- III Stage – Life No. 9. Modified Piano MODEKAL – COVID-19 Anamnesis

The first stage consists of eight movements, resembling the process of the materialization and creation of the piano Universe. It ends with Life I represented by a quote from Sonata No. 9 by Lodovico Giustini.

The second stage depicts the history of piano music presenting quotes from piano works by 30 composers. Their names are given in the charts and performers are free to choose particular excerpts following the composer’s instructions.

The third stage presents the Modified Piano MODEKAL. The major part of the piece was composed in the pandemic era and no artist could avoid this problem. The structure of the third stage is based on a Facebook post by the famous young Georgian writer Guram Megrelishvili, who described in detail all stages he went through being infected with Covid-19. Thus, the third stage represents the anamnesis of Covid-19.

The piece ends with CODA – other perspectives

Though, how do we answer the question reflected in the title of the piece? Actually, we started research trying not to search for answers, but rather to prove that piano music did not come to an end. That it is just the end of one of its many lives. That the instrument still has the potential to inspire composers to compose innovative, truly contemporary music that reflects the spirit of the epoch. We hope we proved that. Maybe in this case we are not objective, but rather subjective researchers in love with instrument of great historical importance. But, one of the characteristics of artistic research is that it accepts subjectivity, as opposed to the classical scientific methods.

Artistic researcher Johan Verbeke states that:

The arts, design and architecture are not involved in an exact logical understanding of our world (as are the exact sciences), but they complement this with a knowledge field which builds on human experience and behaviour and is interwoven with cultural and societal development… [They] build on their own specific positions in relation to reality.

(Verbeke 2013)

We think it is this subjectivity that enables not only the arts, design and architecture, but also artistic researchers to build on their own specific positions in relation to reality.

Conclusion

Our artistic research could be considered as one of the first purely artistic researches conducted in Georgia. Artistic research is not officially recognised in the Republic of Georgia. Music and Art Universities offer to musicians and artists special doctoral programs that give doctoral students opportunities to examine issues related to artistic practice, performance and composition practice based on theoretical and practical knowledge. Though, the focus of such researches is set on a musicological, critical, scientific approach. This is reflected in the results of those researches that must be presented in written form employing academic forms of writing. Having concentrated on “the poetic, the creative, and the literary, and the media-sensitive” forms of reflection and writing (CARPA7 6 November 2021) in our artistic research we attended CARPA7 to get an answer on the question: are artistic forms of writing able to precisely convey the research concept and conclusions? We got our answer. We encourage you to get your answer.

Acknowledgments

This paper is an output of the research project Development of Artistic Research Methodology on the Example of Exploration of the Piano of the 21st Century and its Future Perspectives. The project, as well as this work, is supported by the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia (SRNSFG) [grant number FR-18-4275].

References

CARPA7. Vision Statement. Accessed 6 November 2021. https://sites.uniarts.fi/web/carpa/carpa7/vision-statement

Gasser, Nolan. 1994–2022. “Period: Impressionist.” Classical Archives. Accessed 6 November 2021. https://www.classicalarchives.com/period/8.html

Loesser, Arthur. 1990. Men, Women, and Pianos: A Social History. New York: Dover Publications.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1993. “Clavier music 1992.” Trans. by J. Kohl. Perspectives of New Music 31, no. 2: 136–149.

Stockhausen, Karlheinz. 1963. “Zur Situation des Metiers (Klangkomposition)“. In Texte zur elektronischen und instrumentalen Musik. Volume I. Köln: DuMont Buchverlag, 45–61.

Verbeke, Johan. 2013. “The Intrinsic Value of Artistic Research.” In SHARE: Handbook of Artistic Research Education, ed. Mick Wilson and Schelte van Ruiten, 123–125. Amsterdam. Dublin, Gothenburg: ELIA.

Contributors

Nino Jvania

Nino Jvania studied piano and musicology at Tbilisi Conservatoire and R.Schumann-Hochschule Düsseldorf. She is the prizewinner of various international piano competitions and the author of several scholarly works and a monograph. Currently she leads the artistic research project Has Piano Music Come to an End? that is conducted together with a composer Eka Chabashvili and a pianist Tamar Zhvania and financed by Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia.

Eka Chabashvili

Eka Chabashvili – composer, prizewinner of international competitions, Doctor of Musical Arts, Associate Professor at the Tbilisi State Conservatory, Secretary of the Dissertation Board, Manager of Doctoral Studies, Director of Contemporary Music Development Center, Organizer of Woman and Music festival. She has participated in various international festivals and scientific conferences and has been invited to conduct master classes on composition at the USA and European Universities.

Tamar Zhvania

Tamar Zhvania – pianist, Doctor of Musical Arts, teacher at Tbilisi V.Sarajishvili State Conservatoire. She studied at Tbilisi Conservatoire and R.Schumann-Hochschule Düsseldorf (as a DAAD Grant holder). Prizes: I Prize and the Special Prize of the Mayor of Vienna at the Vienna International Piano Competition 2006; Diploma of Honor at IV Bialystok International Piano Duo Competition 2008. Tamar also participates at international conferences and publishes her papers in national and international periodicals.