Abstract

Departing from the question what a machinic self is that exerts a thought or will when put into operation, this text proposes that human-machine and human-human ensembles become more interesting from an artistic research perspective when conceived as “moving along”, rather than investigating them through diachronic or synchronic coupling. By way of looking at the projects Algorithms that Matter and Simultaneous Arrivals, a third position is identified with the notion of simultaneity. A “time-space” is created that enables and encourages contact without the identification of positions or rhythms. While the selves of the ensemble’s constituents are not dissolved, the focus moves on to the “within” that such time-space provides, allowing different forms of collaborative making and practising and to potentially overcome the divide between self and other. To make use of dramaturgy for a simultaneous, circulatory work, it has to be developed from a narrative logic of and-then into a topology of or-there.

Automation and the boundaries of machines

Automation, beyond a rational move to increase industrial productivity, yields the joy of watching another entity solve a task. Task and goal are given, and the joy rests in anticipation of the completion and in the material unfolding through the machine’s operation in time and space. Watching the pebble sorting machine Jller by Prokop Bartoníček and Benjamin Maus (2015), one enjoys the robotic movement more than the task’s completion. The time and space opened by the machine’s selected strategy with its distinct aesthetic consequences is what interests us. Automation is defined by rules, and they can be performed by humans as well, where it is joyful to play by the rules, as long as there is the possibility for some opening, a form of interpretation.

While automation refers to self-operation, machines are not born that way, so there is the verb “to automate”, as the hand of a creator sets something into a thought or movement only seemingly folded onto “itself” thereafter. As a diachronic process, the pro-gram, the pre-writing or meta-writing, is followed by an executive writing. The notion of an automaton collapses when asserting complete control over its designation, since now the machine no longer has a self-conduct that could be controlled (cf. Burroughs 1978).

One would have to move to a more emphatic term, autonomy – self-governance or self-rule. Autonomy as rule established from the inside of a system is a way saying that the machine transcended our prescribed logic in some sense. In many approaches of generative art, forms of rewriting are possible within the machine, or the machine is constituted by a set of agents which interact with each other and thereby produce complex behaviour, and one wishes for emergent properties to appear. In other words, there is no shortcut to the goal, the machine has to perform, it has to be traced empirically. As the secondary writing process is no longer perceived as executional, but as a voice in its own right, and with the possibility for entirely different and surprising outcomes, we consider the machine more on par with our own species.

A self-modifying automaton is not required to understand the performance of computation itself as a source of autonomy, when engaging with what I call algorithmic experimentation, where the “self” encompasses the symbiotic forth and back between human and machine in an iterative reconfiguration. What crosses the boundary of humans “into” the machines, is an investment that we make, an engagement with the process of programming, building, configuring, debugging, breaking; establishing – despite the machine’s physical exteriority – a closeness or almost intimacy. This state has been described using Lacan’s term extimacy (Rheinberger 1997, 24). It would also imply all the cultural and historical conditioning that makes it possible to have and to program this machine.

All the strangeness of the topology thus obtained results from our conception of self and other, or subject and object of an action. Not only are the location and shape of boundaries subject to debate, but they are in fact relationally enacted. This is the point Karen Barad makes in Meeting the Universe Halfway (2007) in which she builds the idea of intra-action on analogies to quantum physics and the thought of Niels Bohr, among others. Boundaries are perceived by forms of touch or contact, no matter whether that refers to physical or mental or other types of boundaries. Analysing the scanning tunnelling microscope, Barad notes that depending on how the machine is configured or operated, it becomes either a reading or writing machine. A boundary is first and foremost a site of force acting one way or another, and an example more readily verified in everyday experience is Bohr’s phenomenological description of using a stick for orientation in a dark room:

When the stick is held loosely, it appears to the sense of touch to be an object. When, however, it is held firmly, we lose the sensation that it is a foreign body, and the impression of touch becomes immediately localized at the point where the stick is touching the body under investigation.

(Bohr 1961, 99)

The continuous transition between sensing and actuating, between reading and writing, becomes even more interesting when what is being touched, and what we are being touched by, is understood as endowed with reciprocal agential properties, applying equally to inanimate matter, laboratory objects and so forth. These properties, I argue, appear largely due to the personal and transpersonal investment these things have received.

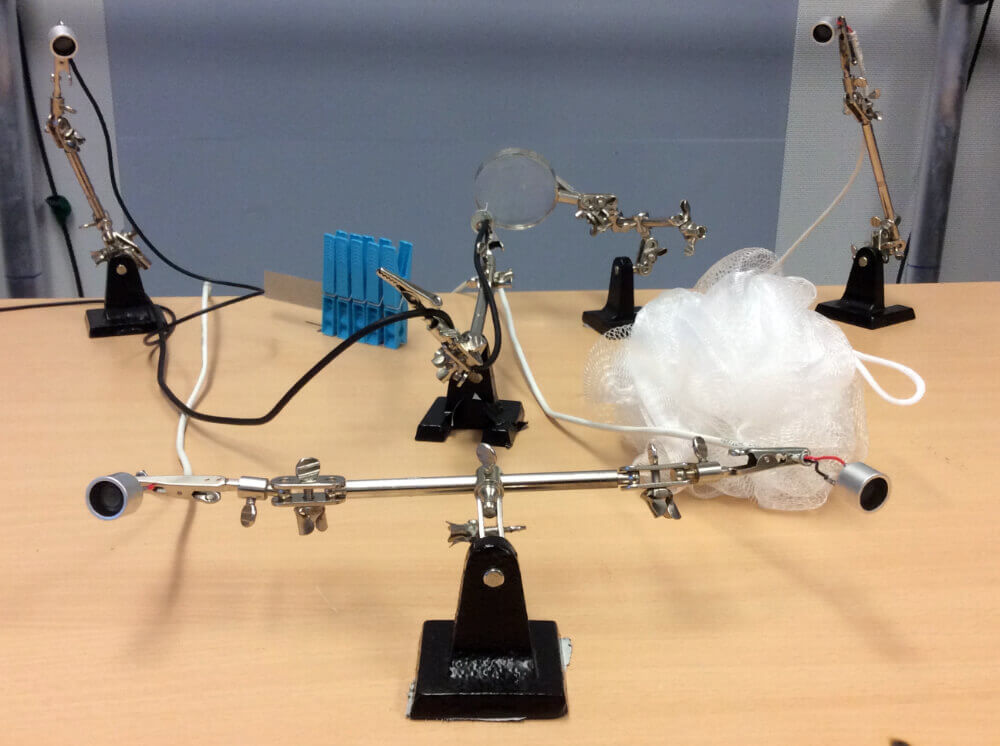

The “things” we were investigating during the artistic research project Algorithms that Matter[1] were algorithmic sound practices, their material embeddings, as well as their potential for sharing among different artists-researchers. We worked with incoming artists that covered a broad range of approaches, each bringing personal projects. The first one was computer music pioneer Ron Kuivila, who was developing a new live electronic work based on ultra-sound, a medium he had been working with for nearly four decades. In ultra-sound, acoustic sound signals with frequencies beyond the human ear’s hearing limit are employed, they are thus, in principle, inaudible to us; however they can be modulated and translated into the audible spectrum. Something very particular happened, when we experienced interacting with Kuivila’s ultra-sound setup in the lab. In Fig. 1, the four cylindrical objects are ultra-sound transducers that can be either emitters or receivers of sound waves, which are easily reflected and redirected by sufficiently hard surfaces, including the desktop and the convex glass lens.

Not unlike infra-sound, where the modality of hearing transitions into a haptic sensation of the long wavelength vibrations felt by the entire body, with ultra-sound the extremely short wavelengths afford a tactile sensation when feedback systems are built, as the tiniest movement of bodies in space alter the reflection patterns of the inaudible waves and consequently of the modulated audible waves, producing a synaesthetic experience I would describe as contact with the ether. Phenomenologically, the algorithmic formulations extend into the space surrounding the performer. In the piece Listening to the Air,[2] the human is performing boundary work with a partly automated, partly autonomous system. This idea is extended to multiple humans in collaborative practice, as shown later.

Moving along: simultaneity, co-presence

What is enabled by touch is the sensation of co-presence. A curious situation is being in touch with oneself. In the text On Touching, Barad notes that it creates “an uncanny sense of the otherness of the self, a literal holding oneself at a distance in the sensation of contact” (Barad 2012, 206). In her piece I don’t exist yet (2020), video artist Susanna Flock constructs a witty and playful scenery around green blob like objects that are used in film and video to stand in for later replacement by computer-generated-imaging. The piece is narrated by the blob speaking from offstage, contemplating its transitory identity as a stand-in, as well as the implications of being and being not (or not yet) a body. It is from this latter question that a similar observation as Barad’s arises: “Only if we touch ourselves we are feeling at two places simultaneously.” This line stood out for me at the time we were building the artistic research project Simultaneous Arrivals[3] and forming an understanding of what the concept of simultaneity may entail – how it may be useful to understand being-with and working-with.

Simultaneity derives from the Latin word “simul” which stands for “together, at the same time”, so simultaneity could be understood as sharing a time-space, but in a particular transparent manner. For me it implies a co-presence where the elements sharing a togetherness are not linked by hierarchy or cause-and-effect, they are not interlocking such as to create any sort of synchronisation, maybe not even “synchora” or spatial identity, strictly speaking. In the project, thus we also speak of being tangential or being adjacent. A simultaneous situation is an instance of sharing time and space without them becoming the same, in other words two (or more) temporalities and two (or more) spatialities meet.

In my personal work, I am often interested in what happens when the interlocking of human time and computational time are loosened, to allow different temporalities to meet; to compose or set up a temporal regime other than so-called “real-time”, a regime that moves independently or at least distanced from the temporality of the experience of the visitor or audience. A visual piece in which this plays a role, is Inner Space (Fig. 2). It is a multi-channel video installation, probing the periphery and materiality of algorithmic processes, and made of a series of independent miniatures. One of them, titled Site, is based on a kind of digital long term exposure in greenish and yellowish colours, originally referring to the space outside the gallery, which is observed through a differentially accumulating procedure. Sanded stripes attached to a window, people passing by, producing strangely oscillating appearances and disappearances. A constant change of light conditions. It is both a time-lapse, in terms of its image acquisition, and a slow motion in terms of its further processing. It is thus conflating the interference of machinic perception with an urban situation, and the space created internally through generative processes. The multi-channel situation, in which each screen runs its own loop, and spreading the screens in different angles across space, maintain that the viewer is not tied to a particular time-space frame.

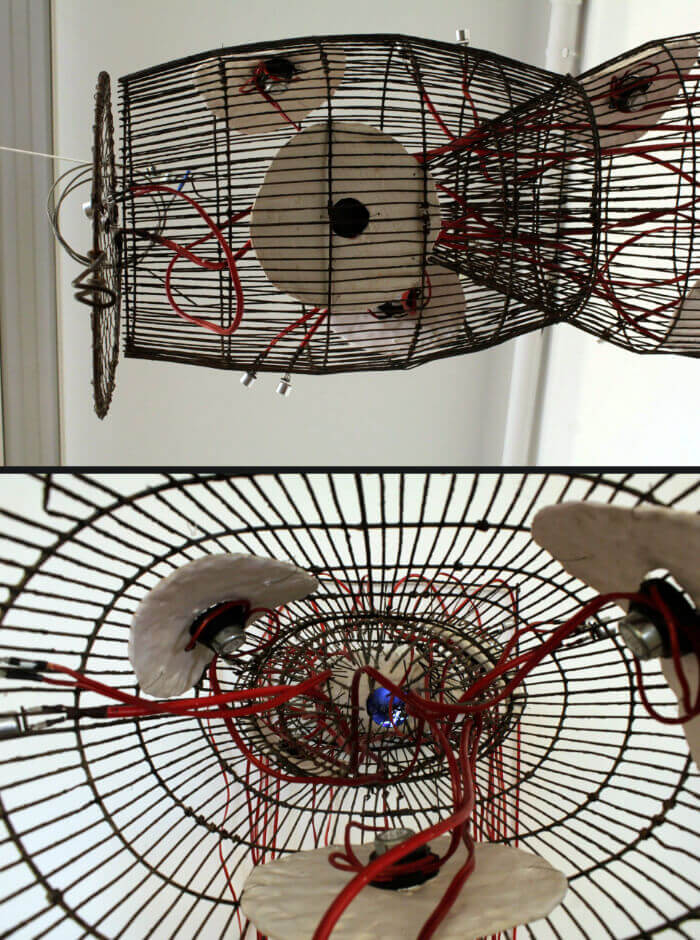

While in this piece the visitor’s presence is not sensed by the machine, in Körper α (Fig. 3) sensing is the primary source of temporal-spatial interference. In terms of circulation, the theme of the next section, it is also an attempt to understand how one could (or could not) continue to work with the proposition made by another artist. Körper α was co-created with David Pirrò during the first year of Algorithms that Matter, and it points to engagement both with the second incoming artist in the project, Erin Gee, in whose work corporeality plays a role, and with the first incoming artist in the project, Ron Kuivila. Ultra-sound circuits attached to a metal body pick up, through the Doppler effect, a spatial image of visitors approaching and retreating from the body, translating it to a strange spherical projection seen through a round screen embedded in the piece. This projection, in turn, is fed to a topological learning algorithm which continually adapts its representation of the body’s surroundings. The performance of this algorithm, that is the sequence of adjustments, insertions and deletions in its representation, then becomes the source for sound production, as it is coupled to a dynamic feedback network, heard through small speakers placed around the body. The form of co-presence of visitors and machine hinges on their interaction, but the respective temporalities and spatialities are strongly decoupled. One is invited to explore what the body is doing visually and sonically, and one may understand how presence is important, but there is no incentive to “play the body”, to “act in front of the body”.

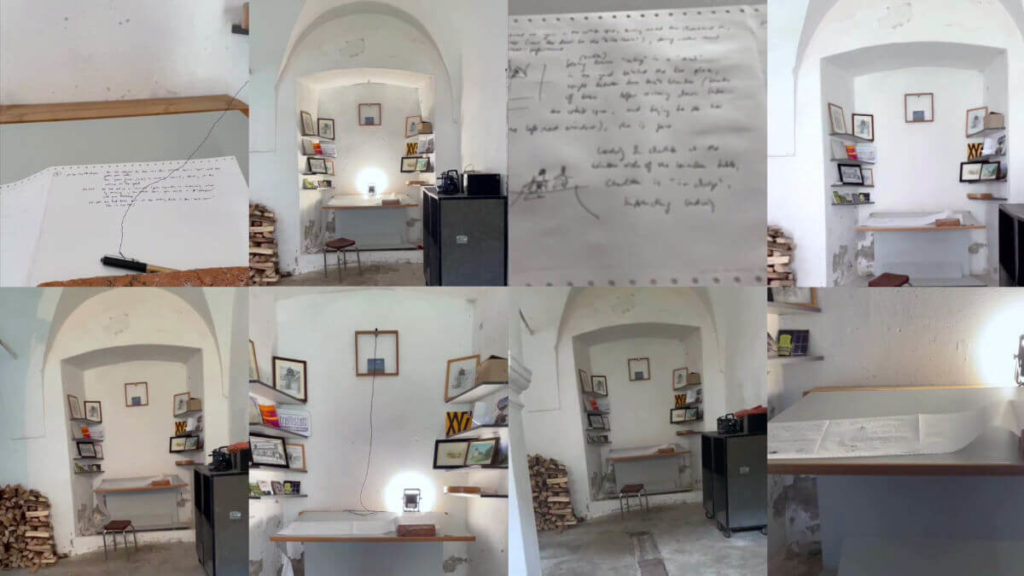

Two recent examples are taken from the first interval of Simultaneous Arrivals. The first is a series of intermedia entities called Rogues.[4] They are equipped with different sensors that obtain data from their environment, especially movements made by people and any sounds occurring around them. Rogues are built to respond to their impressions on different time scales and through forms of indirection, so that the temporalities they produce – while influenced by their surroundings – exhibit a perceivable independence, thus suggesting to the visitor to spend time with them and accept them as they are. I brought two partially completed Rogues to the site of Schrattenberg, a rural former farm compound in Austria now used as an artist space, and which we inhabited for two weeks of intensive retreat with the project team. Here, the Rogues “marked” specifically chosen threshold locations which one could visit at any time, in one instance offering a place to meet and discuss their future (Fig. 4).

The second example is a video walk experiment conducted around the same site and during the same period of time (Fig. 5). It is based on a performative exercise made daily by one of the incoming artists-researchers, Charlotta Ruth. She was moving along herself or her memory, but also moving along the Schrattenberg site. The video walk is therefore also a practice both of documenting the group’s activities and of creating possibilities for encounter and coincidental contact, without any of us others being required to perform along. First and foremost an activity simultaneous with what others were doing, this could be seen as a tentative step away from automation, by integrating these possibilities for contingency and contact, towards a movement with us and the site, encircling our group project, an inner course or endo-mation.

Circulation and simultaneous arrivals

Simultaneous practice can be helpful or even constitutive for a different kind of collaboration. It has to be shown how something cohesive can emerge from these seemingly non-committal meetings. I would like to think of a type of collaboration and togetherness that is neither a simple collage of individual positions – a group exhibition whose coherence is merely given by a curatorial hand – nor based on the identification of positions or collectivisation. Such a viewpoint is developed by Jean-Luc Nancy in Being Singular Plural, which centres around the term singularity rather than individuality, and consequently there is no place for delimited totalities endowed with autonomy:

The concept of the singular implies its singularization and, therefore, its distinction from other singularities (which is different from any concept of the individual, since an immanent totality, without an other, would be a perfect individual, and is also different from any concept of the particular, since this assumes the togetherness of which the particular is a part, so that such a particular can only present its difference from other particulars as numerical difference).

(Nancy 2000, 32)

As we live together, each one constitutes the “origin” of the world, as Nancy calls it, but cannot be thought of except as being with others, contiguous with the other “origins” through an ongoing process of singularisation (of unique instants). Nancy’s approach offers an interesting possibility for solving the impasse of communality vs individuality.

This possibility is based on togetherness as space and spacing (or distancing), which are necessary to both maintain the differences and to set communication into motion, described as the circulation of meaning. The concept can be related to touching, which emphasises the heterogeneity of surfaces and the effect of separation. Touching is to be thought not merely in the physical corporeal sense, but also including what it means that thought touches, that it naturally has to make leaps as it is shared. Because of this separation, each “origin” – the incommensurable creation of the world that is “me” or “you” – remains incomparable, inassimilable. We are, as Nancy says, absolutely strange to each other, and to ourselves. There is no point in becoming the same; we have to base our doing on this presumption of absolute strangeness, and this creates, as a positive force, curiosity about the world, ourselves and others.

The tension field of near-and-distant at the same time is well captured in the word “curiosity”. Curiosity describes the attraction to a strangeness, which is simultaneously deferred or reworked, so as not to collapse in fulfilment and elimination of strangeness, in the appropriation of the position of another; one upholds the spacing. I would argue that in most cases of collaborative artistic work, or at least in the successful cases, this curiosity remains the centre of the work itself. If extimacy is pointing from the tension field towards us, perhaps curiosity could be understood as pointing from us towards the tension field.

In Simultaneous Arrivals, we aim to understand how one could enact a kind of multiplicity, where heterogenous propositions are circulated, for others to react on or engage with them (at their choice) while staying faithful to their own practice. One of the cases that motivated us to build this project was the sound installation Through Segments (2020), a collaboration among four artists that aimed at creating a cohesion between individual compositions. The process was in some sense made easy, as we shared a certain vocabulary, we could read and understand each others’ code, and we worked in the same medium, sound. But we also had to take into consideration that, as the project terminated in an exhibition space, our four distinct compositions would mix acoustically. Primarily born out of the constraints of the pandemic and our various concurrent commitments, we established an asynchronous workspace on the Research Catalogue online platform,[5] as a skin delimiting the project, a space to visit and work each in their own rhythm and time resources, with a negotiated protocol of dialogue through questions and answers, verbal or non-verbal. One could decide the level of proximity or distancing, and the digital online sub-spaces could be either personal or shared.

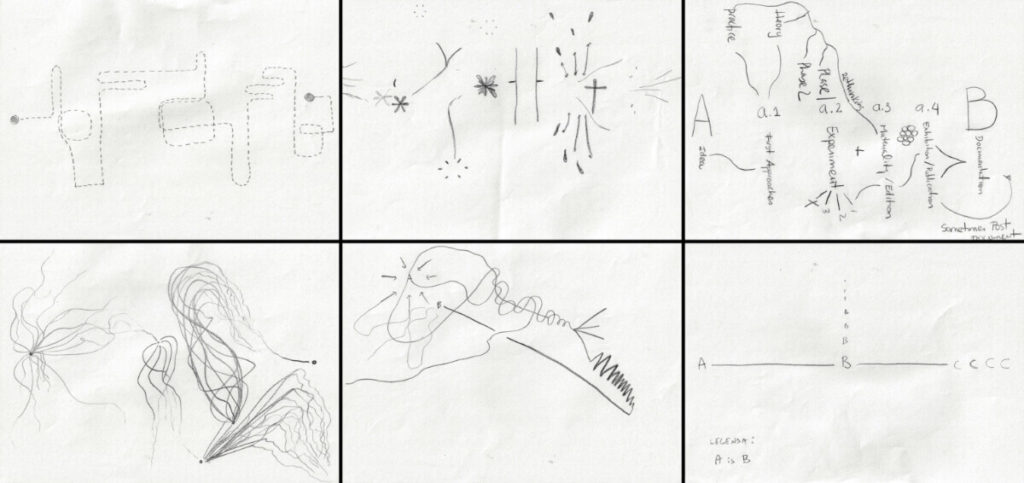

In Simultaneous Arrivals, we want to see what happens in greater heterogeneity, by bringing together artists-researchers from different disciplines, and we also want to understand the process more systematically. We address the time-space needed for togetherness through the hypothesis that physical working spaces will strongly impact on the unfolding of the collaborative process, and that we can make out a transversal connection with other forms of spaces, such as cognitive and aesthetic spaces, which to some degree can be elicited through dialogue and exercises (cf. Fig. 6) and studying affordances of shared working spaces.

As in the virtual case, the physical space delimits our action radius and stimulates us, hopefully, to enact forms of place-making, of slowing down, of arrival, of a new pattern of movement inside the group which I call endo-mation, the course within our togetherness. It is derived from a technique we practised and called endo-documentation, wherein instead of designating a non-participating person to be in charge of the project documentation, the responsibility is for everyone to contribute to the documentation, to oscillate between one’s own work process and the observation of what is happening around.

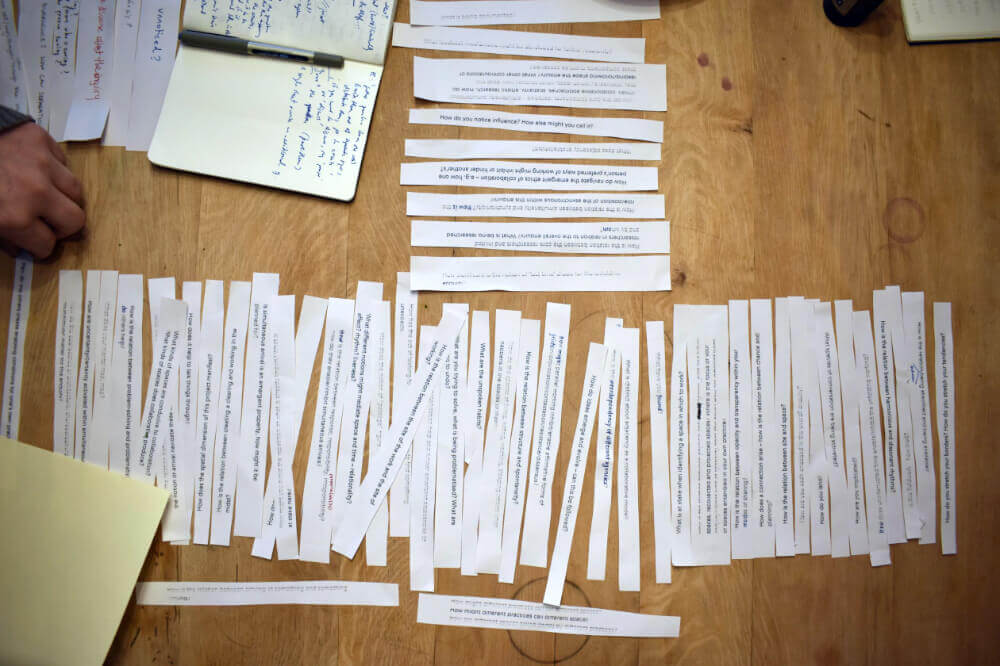

The list of forms of circulation we tried out among and between the individual work includes: A logbook installed at a fixed place, so that whenever one passes by, one can note down perceptions of what the others are doing. Daily sheets created in a silent group situation after breakfast to capture what appears important to us from the previous day. A dedicated location or “swap space” where either materials and tools can be proposed for others to use, or written requests called “soft invitation” are left to feed back to someone’s work. A blackboard to announce invitations to meet at a given time and place, for instance to discuss an ongoing artistic process. Question walks, which emerged from work conducted by artist-researcher Emma Cocker who joined us as facilitator and developed a catalogue of questions pertaining to the research objects; in a first step, we filtered these questions by our resonance with them (Fig. 7); we would then create different pairings among the team with each pair deciding on two questions and a time and place for a walk taken together, spending around half an hour, during which the questions could be elaborated or even “solved by movement”.

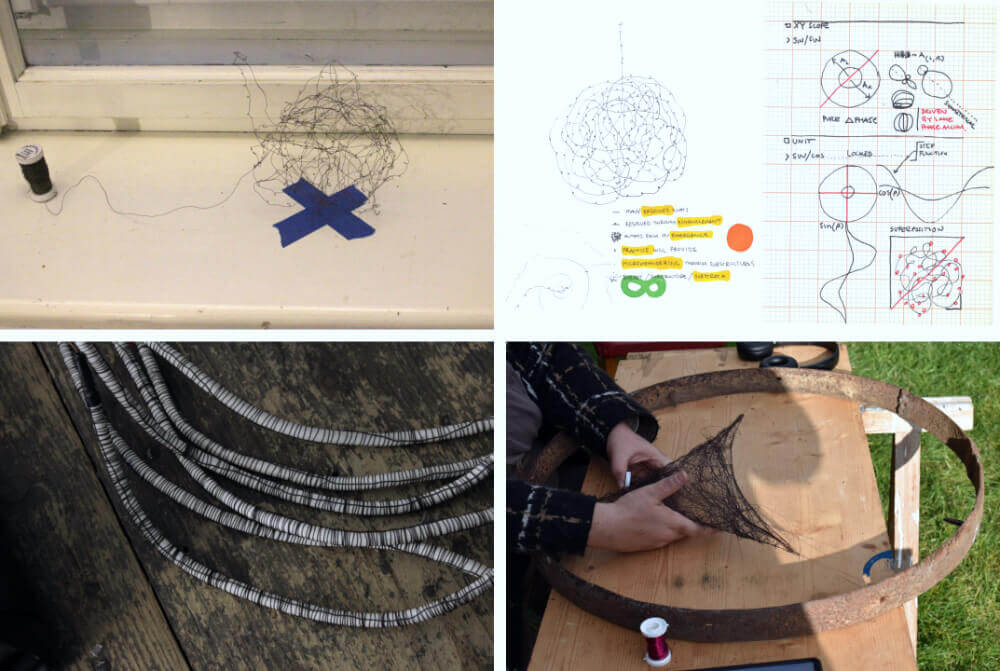

As expected from the variety of artistic languages and approaches, some techniques and invitations worked better for some, and were less useful for others. For instance, regarding the “swap space”, artists with practice in performing arts were more ready to create and engage with the written letters, whereas artists with practice in installation could figure out what to do with the physical objects without further instructions or context. Wishing to map new forms of collaboration, a danger lies in the temptation to trace contact only through these manifest and direct techniques, or to identify mutual influences among the group on reified surfaces. A different kind of tracing was carried out using the concept of boundary work, where ideas, materials and forms cross time and persons under constant transposition (cf. Fig. 8). These crossings are subject to speculative interpretation and difficult if not impossible to “prove”, but their value may lie specifically in the discursive speculation within the group.

Spatial dramaturgies

Regarding the demands and expectations of artistic research, making a highly experiential project readable for others, peers outside the project and/or its time frame, is particularly difficult. An important aspect of Simultaneous Arrivals is to connect one interval of the project to the next, in which new artists-researchers enter the process. This indicates a different kind of circulation that must be operable across a larger time frame and spatial gap.

There are two steps needed. First, many of our interactions were through spoken or written word accounts. On the practical side, specific physical constructions were built, sounds composed, videos edited, sketches drawn, found objects collected. A repository is needed in which both the language-based and non-language-based elements are stored and retrieved. But these manifest files and objects often fail to capture the “essence” of what happened during a project. The accounts were situated, in particular places and atmospheres, which are still attached to them through the experiences the original team had as the “first readers”. Atmospheres and experiences are difficult to capture.

Can “dramaturgy” help? In the fields of sound art and installation art, my main practice, the concept of dramaturgy is foreign, some would even argue that sound art is precisely non-dramatic sound work in opposition to music, performed on a stage. One could say, sound artists work rather with lyrical than dramatical forms. Dramaturgy may be defined as the organisation of an audience’s experience through time (Kyung-Sung et al. 2022, 278). What happens when we move from an artistic practice to an artistic research practice? In this moment the audience changes. Who is it who wants to learn about a research process? And how does somebody learn about the process? For me, it is easier to align somebody visiting an exhibition with somebody visiting a library rather than with somebody going to a concert. Why? A performative situation tends to be one, where space is a function of time; and an installative situation one, where time is a function of space. In the mentioned definition of dramaturgy, time is the variable that is shaped by composition, and the material production of the stage – its spatial organisation – would be in support of this primary function. Visitors to an exhibition or a library may spend a lot less or a lot more time with the activity. They may also walk around and direct their attention to different things, and different pieces, and perhaps return again. I come to a gallery to roam around, to inspect the propositions put forward at my pace, unroll the experience through my movements. To allow for pace, of a visitor, audience, reader, is paramount. Pace is the rate and manner of movement that emerges from contact between individuals and spaces, it is complex and multi-faceted and includes the situatedness and atmospheric properties of an environment (Rutz 2023, 71).

One can make attempts, with a well thought design, in aiding an audience in finding a way into a work, one can make offerings, one can provision for a heterogeneity in the background of people approaching the work, but one cannot design an experience. Let us instead imagine a spatial dramaturgy, which organises opportunities for readers, visitors, audiences, peers and co-researchers to access the research, based on the pace and multi-perspectives brought by these “recipients”; which provides and conditions a physical or virtual space that the recipients could explore, without the need to have one “complete narrative” in a given time frame. One thus changes from a narrative logic of and-then to a topology of or-there.

At the end of Algorithms that Matter, we were looking for a suitable form to make its traces and outcomes available, beyond the accumulative documentation that had happened through a number of Research Catalogue expositions, journal and conference articles, exhibitions and performances. Since a vast amount of materials had already been made available through the Research Catalogue, it was obvious to build on this, and coupling a software that crawled and indexed these materials with a software that rendered an experimental database-like interface, we created the so-called Meta Exposition (Pirrò et al. 2021).

For Simultaneous Arrivals, the digital space clearly limits any spatial dramaturgy that could otherwise incorporate physical movement and physical artefacts. For the final days of our first interval, we rather hastily set-up a physical meta-exposition (Fig. 9), bringing in original sketches and objects as well as prints of photographies, texts and Research Catalogue expositions, installing video screens, and activating the space through different playful queries. This short-term installation also revealed its inherent problem: gathering there as a group for a short time frame rather produced a performative, almost theatrical enactment of a library, it did indeed not provide for the pace and independence of each researcher, the possibility to come there and meet at different moments across a longer period of time.

Our two weeks of intensive retreat functioned better in terms of its spatial dramaturgy. One would need a spatial resource for the entirety of a research project, but it is quite a luxury and seldom available. One illuminating example concerns the artistic research project Rotting Sounds by Thomas Grill, Till Bovermann, and Almut Schilling (2022). Located on the campus of the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, an auditorium formerly belonging to the School for Veterinary Medicine was available to them for the duration of the multi-year project, in order to conduct their research into long-term processes of digital degradation. Incrementally it gathered their different propositions and artefacts, as they were developed and reconfigured.

At the Gustav Mahler Private University for Music in Klagenfurt, we are in the process of setting up a workspace lab for artistic research, which should allow longer term installations besides being a reconfigurable space for doctoral studies. During the second interval of Simultaneous Arrivals in spring 2024, we will use the not yet refurbished premises and try out if a month-long physical meta-exposition is sufficient to work in the mode of or-there.

Notes

1 FWF AR 403-GBL; www.researchcatalogue.net/view/381565/381566

2 For a trailer, see www.researchcatalogue.net/view/386118/431742

3 FWF AR 714-G; simularr.net

4 www.researchcatalogue.net/view/1437680/1437681

5 www.researchcatalogue.net/view/711706/711707

References

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

Barad, Karen. 2012. “On Touching – the Inhuman That Therefore I Am.” Differences 23(3): 206–223. doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943.

Bartoníček, Prokop, and Benjamin Maus. 2015. “Jller.” Online: www.prokopbartonicek.com/jller.

Bohr, Niels. 1961. “The Quantum of Action and the Description of Nature.” In Atomic Theory and the Description of Nature, 92–101. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Burroughs, William S. 1978. “The Limits of Control.” Semiotext(e): Schizo-Culture III(2): 38–42.

Flock, Susanna. 2020. “I Don’t Exist Yet.” Online: susannaflock.net/home/i-dont-exist-yet.

Grill, Thomas, Till Bovermann, and Almut Schilling. 2022. “Rotting Sounds. Artistic Research Practice in Experimental Sound Art.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 19(2): 103–118. doi.org/10.31751/1174.

Kyung-Sung, Lee, Boris Nikitin, Wen Hui, Zhao Chuan, and Kai Tuchmann. 2022. “Shame and Power: A Critical Conversation on the Postdramatic Condition.” In Postdramatic Dramaturgies: Resonances between Asia and Europe, edited by Kai Tuchmann, 271–286. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag. doi.org/10.14361/9783839459973.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2000. Being Singular Plural. Translated by Robert D. Richardson and Anne E. O’Byrne. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Pirrò, David, Hanns Holger Rutz, Daniele Pozzi, and Luc Döbereiner. 2021. Reading ‘Algorithms that Matter’. 12th International Conference on Artistic Research. Vienna: Society for Artistic Research. Online: www.researchcatalogue.net/view/381565/1220979.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Rutz, Hanns Holger. 2023. “After Swap Space: Four Openings.” In Swap Spaces, edited by Nayarí Castillo and Hanns Holger Rutz, 70–77. Graz: Reagenz Verlag.

Contributor

Hanns Holger Rutz

Hanns Holger Rutz is an artist and researcher in sound art and digital art, based in Austria. His works in installation, improvisation and music composition span more than two decades, having extended to other digital and non-digital media. He heads the FWF-funded artistic research project “Simultaneous Arrivals” (2022–2025, Co-PIs: Nayarí Castillo and Franziska Hederer) on novel forms of collaborative artistic processes. Rutz is Professor for Artistic Research at the Gustav Mahler Private University for Music (GMPU) Klagenfurt, AT.