Abstract

The workshop at CARPA6 introduced ‘the communication dyad’, derived from Mind-clearing, merged with the practice of Authentic movement, as a way to enter into relationship with another, and eventually through a screen to an audience. This method, combining contemplation with communication, based on Zen self-enquiry, invites the participants to respond to the seemingly impossible instruction ‘Tell me who you are?’, in the presence of another, and attempts to communicate this inner attentiveness of the self through verbal communication and/or movement. A significant amount of allocated time of this workshop, was spent on dyads, each preparing to see and be seen differently; until the final dyad where a camera will be used to filter the experience. The participants had the choice to film each other, through their own phone or cameras, in one single take of five minutes. With the participants consent, the video portraits were collected and presented on a pre-prepared grid. This experimental workshop introduced the communication dyad as a tool to increase one’s ability to relate and deepen collaborations, through extending beyond the confines of the self into a relationship with another, and eventually through a screen to an audience. Bring your camera / phone.

– – –

I don’t know how to embody my relationship to the Divine,

outside of my relationship to you.

Jane Adler (Pallaro 2007, 244)

Introduction

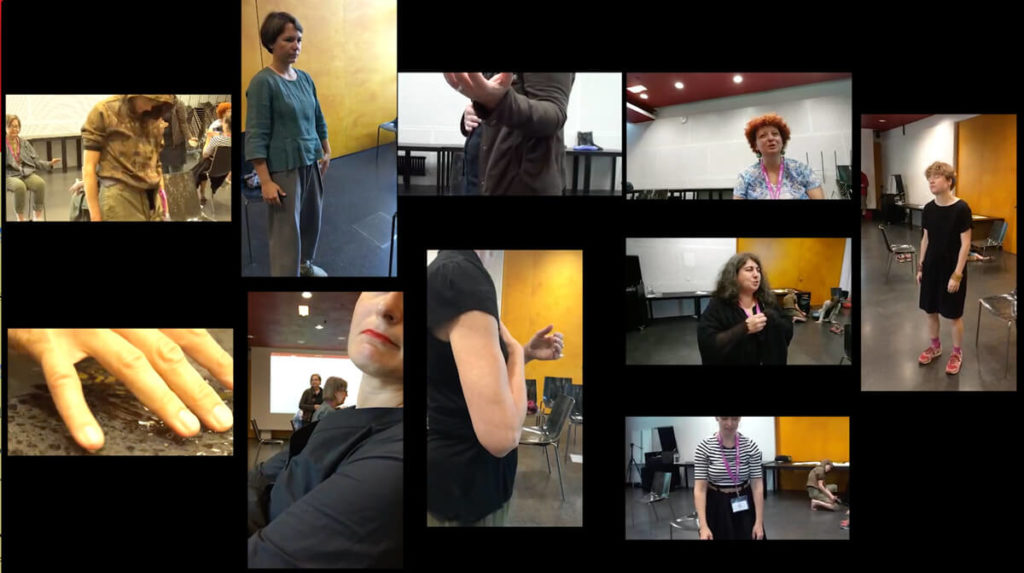

I presented a workshop at CARPA6 2019 entitled: Dyadic encounter between artists, in which participants entered a relating process prior to filming each other with their camera phone. After a discussion, the portraits were collected with permission and gathered on a grid-like video that was informally presented during the CARPA6 event. This workshop is an experiment that I set up as part of my doctoral research at Middlesex University, in which I am exploring the encounter between filmmaker and dancer. It is set within the field of Screendance which in the last fifteen years has been expanding “to include a more research-led approach that de-emphasises the end product to privilege a processual approach to film and dance making” (Heighway 2014, 44).

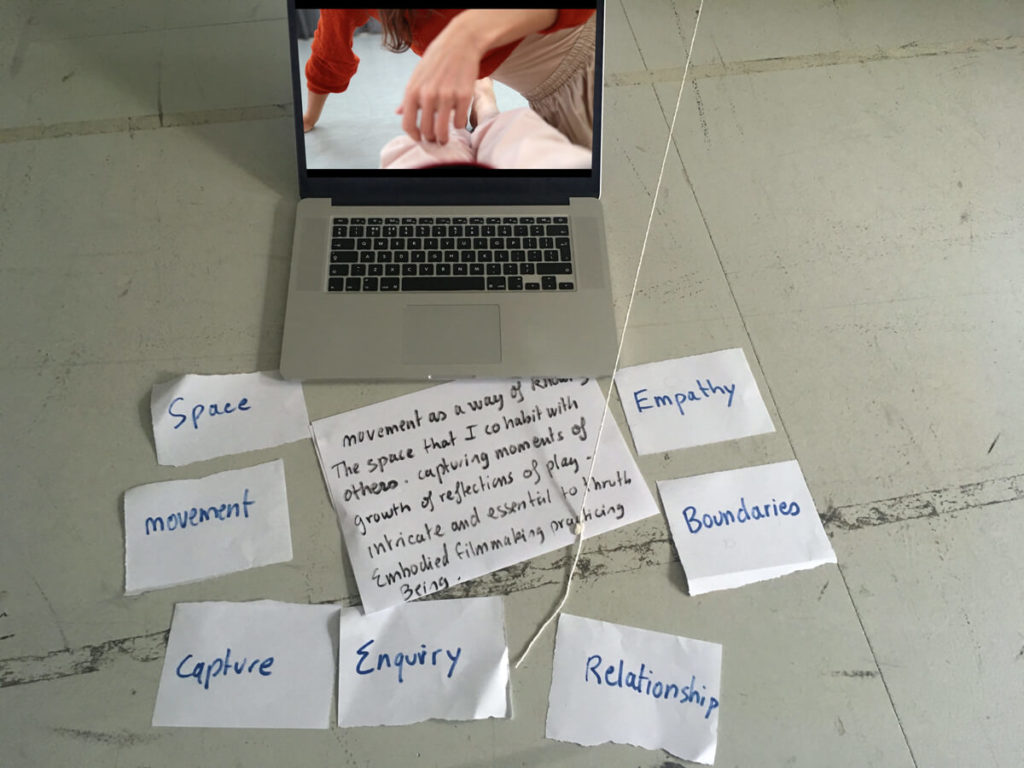

I approach this research as a filmmaker, an Authentic movement[39] practitioner and a Mind Clearing therapist[40], looking to develop a method to work from, and better capture and represent the internal, inner attentiveness of somatically[41] informed dance practices, through an experiential co-created space where the roles of the dancer and filmmaker are inter-changeable and equal.

In a camera dancer relationship, the dancer has no live audience like in a theatre – the camera operator is effectively holding the audience in their hands, as the intermediary between the dancer and the eventual audience. It is important to strive for an ethical relationship between the filmmaker and the dancer in order to cross what Lewis-Smith called “the divide that commonly exists between the performing dancer and the camera operator/director in Screendance-making” (Lewis-Smith 2016, p1). My practice tries to diminish this divide by creating intimacy, the sharing of roles and creating the right conditions in which the observer and the observed can enter a satisfying mutual process of discovery.

Relational filmmaking

In her manifesto for relational filmmaking 2009, Julie Perini states:

Relational filmmakers believe that reality is the consequence of what we do together… Relational films are co-created through careful and playful interrogations of the roles performed by the people and materials involved with the film’s production and reception: artists, subjects, passers-by, audiences, environments, ideas, and things. (Perini 2009, Relational Filmmaking: A Manifesto)

Within relational filmmaking, it’s important to raise affinity, communication and reality between the pair, in order to build the trust of seeing and being seen clearly. Seeing clearly is a process of discernment between judgement and observation, it is a continual process of attempting to see another without projection.

To promote clear seeing and create an initial atmosphere of intimacy in the workshop, I trialled using a process called ‘the communication dyad’, with the assumption that this process would result in cultivating presence to self and others within filmmaking.

The communication dyad

The communication dyad was originally conceived by Eva and Charles Berner in the 1960s and combines the usually solitary practice of Zen self-enquiry with communication to a partner. Berner noticed that being in relation (accountable) with an ‘other’ accelerated the possibility of what the author describes as a direct experience of the self. The communication dyad is usually practiced on the Enlightenment Intensive – a three-day retreat in which participants work intensively face-to-face with a partner to have a direct experience, alternating between asking and responding to the same instruction “Tell me who you are?” in a repetitive cycle of five minutes, punctuated by a bell. The communication dyad, with its set rules and timings, differs from a conversation in that, it is a durational process of enquiry, it allows the ‘content of consciousness’ to be expressed without censorship, and without interruptions from the listening partner – developing the courage to express ‘truths’ that are not usually shared (Fausset 2017). The repetition of the same question allows the responder to enter more deeply into the enquiry, as the content of consciousness is expressed, cleared and received without judgment, the self, further qualified by a certain degree of freedom from preconceived ideas, may begin to emerge, as a felt experience.

I decided to combine these different fields of practice, the dyadic self-enquiry and Screendance as a response to a perceived lack of communication within collaborative practices; and as a way to express an ethical commitment to encountering an other in reverence to their uniqueness and wholeness. This enquiry is aided by somatic practices such as Authentic movement to help to develop a compassionate relationship with self, in order to remain grounded and embodied within the experiential filmic encounter. Because the body is ecstatic – wired to interact with the outside world (Leder 1990); focusing inwards requires practice, it’s not natural.

Developing awareness through inner witnessing is an invaluable tool for the relational filmmaker, who cultivates the ability to tracked movement, sensations and emotions within the self, to make a conscious choice upon the impulses to move towards or away from the other.

The purpose of Authentic Movement is to raise consciousness – can this effort be made visible by a camera immersed in the intersubjective and affective encounter?

Camera

For my workshop, and due to time constraints, there were only two preparatory five-minute cycles of dyads, before the third filmed dyad. Upon further reading and reflection, I now see that the camera immersed in the phenomena of the relationship is an ‘accomplice’ (Colusso 2017) to this process of discovery; meaning that the camera is at once the purpose of this encounter, but also allows the mover to go further in their exploration.

Before pressing the record button, an instruction is raised: the instruction “tell me who you are?” is seemingly impossible to answer, however faced by an other – a response either verbal or physical is expected. Any instruction could be used within the format of the dyad but in the CARPA workshop I offered the following:

Tell me who you are / Show me who you are / Sense who you are

With each command came a different response; whereas, tell me who you are seems to demand a verbal response, show me who you are “becomes a way of saying the unsayable” (MacDougall 2005, 5), and with the idea of putting on a show. Sense who you are, which was the filmed dyad, points more towards experiencing sensations.

The filmmaker was given permission to simply hold the camera without looking through it; allowing accident and chance to enter the frame; presence in relational filmmaking is more important than making an aesthetic choice of framing, which may unconsciously feel like a form of appropriation and exploitation.

In authentic movement, the witness does not move around their partner to get a different point of view and/or a better angle but accepts the view offered by their partner, learning to look at details without ever exhausting the possibilities of discovering something new. And although, I did not express this idea in the workshop, I personally want to adopt this attitude to framing – accepting that the view that is offered is just right for this moment in time.

Steve Hopkins is a filmmaker and Amerta movement[42] practitioner, in his meditative film practice, he describes how every micro movement that the camera operator makes, is a manifestation of the operator’s physical and mental state in relation to the other; it is a trace of where the attention is placed:

If axis and frame ask questions about who we are, where we are coming from, and from where we look, the shot invites us to find answer in movement, and, especially when we take the camera in hand, reveal them to us. (Hopkins 2005: 50)

As an observer of the workshop, I looked in wonder at how the participants engaged with the task of connecting to each other, with a camera, and how their mutual relating abilities combined, to create a five-minute-long shot, in testimony of their presence to self and other.

Developing clear seeing

My research stems from a desire and a curiosity in otherness. I want to hold the frame for an other to be themselves, without anticipations and projections on my part. As a therapist, I have discovered how enabling is the power of the gaze is when it comes without judgment and preconceived ideas.

MacDougall, a leading ethnographic filmmaker advocates daily practice of looking in order to separate looking from desire and meaning which interferes with seeing:

Meaning allows us to categorize objects. Meaning is what imbues the image of a person with all we know about them. It is what makes them familiar, bringing them to life each time we see them. But meaning, when we force it on things, can also blind us, causing us to see only what we expect to see or distracting us from seeing very much at all. (MacDougall 2005, 1)

MacDougall expresses how filmmaker are sometimes afraid to look:

It is the fear of giving ourselves unconditionally to what we see. It seems to me that this fear is allied to our fear of abandoning the protection from conceptual thoughts, which screens us from a world that might otherwise consume our consciousness. For to be fully attentive is to risk giving up something of ourselves. (MacDougall 2005, 8)

The format of the filmed dyad creates a situation to take such a risk, to enter a direct experience devoid of concepts – in which the observer and the observed can become One in experience. The goal of my practice is the diminish the divide that the camera creates and replaced it with the notion of the camera as a membrane that permits consciousness to touch consciousness without a buffer.

With each breath, each eye contact, each perceptible shift, a process of attunement takes place, and for the duration of the dyad, the camera records this reciprocal exchange between two conscious humans in relation to themselves, each other, and the wider context of the world which they are cohabitating.

Developing presence

The mover is not under pressure to create something interesting for the filmmaker, they are solely interested in communicating the content of their self-enquiry. Do they have the ability to exist fully under the gaze of the filmmaker – to be seen without the need to entertain, without the need for approval – without filtering the experience, without guilt or shame? Marie Overlie, an American director and choreographer writes that the performer must work against a protective impulse or hiding mechanism that is triggered by a lack of trust.

Human instinct advises us to hide information, to avoid being fully witnessed by the others as a survival device in daily life. (Overlie 2016, 30)

Janet Adler (Adler 2002), the originator of Authentic Movement, has famously stated that in the West, we are all longing to be seen; yet there is also a fear that we might be judged instead. The communication dyad offers an opportunity to practice being visible simply by sharing the immediate felt sense of the present while in relation. I am lifting the quote below from Jenna Hubbard 2019 who participated in a previous similar workshop held in Coventry, UK:

Being a performer, I want to perform for my partner, to curate their view, to present something of myself that entertains and enlightens. And yet the task feels not that; I am to just be in the space. This is challenging – so much of who I am is relational. (Jenna Hubbard 2019)

Jenna makes the point that it is not easy to relate to an other who holds a camera, it’s a challenge to be oneself, and who are we, anyway, in this world that escapes our grasp!

How was the workshop received?

I adapted the delivery of the workshop according to its lived experience, the room, and the participants themselves. I acknowledge that there is an ethical concern in using the communication dyad within a conference setting, in which participants may be triggered or find the situation unbearable. I was reminded about the importance of giving the participants the agency to simply step out without explanation and judgment. Facing an ‘other’ may feel confrontational and someone suggested to try it while walking. This would be a very interesting development that I wish to pursuit.

A participant of the workshop mentioned the importance of allowing time to watch the rushes together with their partner, and upon reflection, I should have reserved time for this – as reviewing the footage together is key to relational filmmaking; and offers further opportunity to make sense of reality and affect within the partnership.

It was important for ethical reasons that the video recording resided in one’s own phone, therefore the participants swapped phones prior to recording. A couple of participants mentioned that they cherished this gift of a portrait on their phone and that they may look at it from time to time.

Conclusion

My intention as an artist is to focus on the relational within Screendance; in which the dancer, moving from a self-absorbed space, is held by the conscious and empathic gaze of the filmmaker. At first, the coupling of the communication dyad and a camera seems odd and somehow forced, but instinctively, I feel that this transformational process that allows satisfying human contact, could lead to interesting research into relational filmmaking within Screendance.

In this current political and environmental climate, there is a need to look within at our own behaviours, and acknowledge personal trauma and ways to go beyond it. Now is the time to have frank exchanges with each other, and eventually to an audience. Filming is a form of touch, my intention to touch the other with my camera, while rendering visible the mutual connections that unite us through our common struggle and shared histories – but also through the sheer joy of being together.

Please contact me if you are interested in taking part in this research. D.rivoal@mdx.ac.uk

Notes

39 Authentic movement was invented by Mary Starks Whitehouse (1911–1979), and further developed by Janet Adler. A person follows their internal impulses to move with eyes closed, in the presence of a witness, while also tracking the experience, themselves, from within.

40 Mind clearing is a one to one therapy aimed at improving communication created by Charles Berner 1960.

41 The term somatic was first coined by Thomas Hanna (1970) to describe this type of practice; it is now an internationally recognised field (ISMETA 2015).

42 Amerta movement is a form of non-stylised movement practice that draws on free movement, led by Suprapto Suryodarmo.

References

Adler, J. 2002. Offering from the Conscious Body: The Discipline of Authentic Movement. Simon and Schuster.

Bloom, K., Galanter, M., Reeve, S., 2014. Embodied Lives: Reflections on the Influence of Suprapto Suryodarmo and Amerta Movement. Triarchy Press.

Colusso, Enrica. 2017. The space between the filmmaker and the subject – the ethical encounter: Studies in Documentary Film: Vol 11, No 2 [WWW Document], n.d. URL tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17503280.2017.1342072 (accessed 12.7.19).

Fausset, Ursula. 2017. Ordinary truth. In British Gestalt Journal. www.britishgestaltjournal.com/features/2017/10/23/ursula-fausetts-ordinary-truth.

Heighway, A. 2014. Understanding The “Dance” In Radical Screendance – the International journal of Screendance, volume 4: p. 44.

Hubbard, Jenna. 2019. Tell me who you are… Arts University Bournemouth Performance as Research Group. URL aubperformanceasresearch.wordpress.com/2019/07/08/tell-me-who-you-are/ (accessed 12.7.19).

Leder, D. 1990. The Absent Body, 1st edition. ed. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lewis-Smith, C. 2016. “A brief history of the dancer/camera relationship.” Moving Image Review & Art Journal (MIRAJ), 5 (1–2): 142–157. Official URL: dx.doi.org/10.1386/miraj.5.1-2.142_1

MacDougall, D. 2005. The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

Overlie, M. 2016. Standing In Space: The Six Viewpoints Theory & Practice Softcover [WWW Document], n.d. The Six Viewpoints. URL sixviewpoints.com/store/standing-in-space (accessed 11.29.19).

Pallaro, P. 2007. Authentic Movement: Moving the Body, Moving the Self, Being Moved: A Collection of Essays – Volume Two. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Perini, Julie. 2009. INCITE! Relational Filmmaking: A Manifesto, [WWW Document], n.d. URL www.incite-online.net/perini2.html (accessed 12.7.2019).

Whieldon, A., 2015. Mind Clearing: The Key to Mindfulness Mastery. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Dominique Rivoal

Dominique Rivoal is a current PhD candidate in Department of Dance at Middlesex University, working within the field of Screendance, aiming to develop a method to work from, and better capture, the internal, inner attentiveness of somatically informed dance. In order to grasp a direct experience of the world, and investigate the interpersonal relationships at work within the film-making process, I am using the emergent method of Mind Clearing (Charles Berner) coupled with Authentic movement (Whitehouse).