Abstract

In this paper I propose a model of research design developed on the basis of my own practice as artistic researcher, as educator and supervisor at various arts universities in The Netherlands. Departing from Borgdorff’s notion of “methodological pluralism” (2017), the design of a research strategy is consequently regarded as a creative process, with a strong emphasis on how emergence can “do its work” – in both the design process and while carrying out the research. I intend to propose a vision on methodology that provides a conceptual-philosophical grounding, yet at the same time offers a concrete, hands-on approach and technique. In response to Erin Manning’s provocative text “Against Method” (2015), the discussed model of research design understands “methods” as being crafted from inside out, from the very experience and reality of playing and making; permeated with emergence rather than making use of predefined research methods: the notion that artistic research, even when well-designed, always remains in-the-making, emerges through doing, and thereby takes into account the various (possibly yet unknown or unrealized) modes of knowledge that might be produced. How do we as artist researchers, and as teachers of artistic research, actually design such research, while taking aspects inherent to the performing arts, such as ephemerality or collective processes, into account?

– – –

Introduction

This contribution outlines the conceptual core of an ongoing post-doctoral research project at the HKU University of the Arts in Utrecht: an approach, or a model, for artistic research design. The described model has been developed based on my own practice as artistic researcher, educator and supervisor at various arts universities in The Netherlands. In my view, methodology in artistic research often either still leans (too?) much on established models from mostly qualitative research traditions – relating to and adjusting these methodologies rather than relying on their own, intrinsic methodologies, including discipline-specific modes of knowledge – or, on the other end of the spectrum, conducts research in an overly loose fashion, including the occasional ‘everything in an artistic process is research’ statements. I do not mean to suggest, especially with the first point, that all well-known, defined and proven methods should be abandoned, but rather aim to explore the middle ground between these two extremes and to take one step closer towards a methodological approach that prioritises what is specific and essential to the arts.

In this text I aim to share the state of the project at this moment, in particular the design model that lies at the heart of the project, even if still in progress. The research project Common Ground works across various faculties of the University of the Arts and aspires to two explicit types of connections: first, between the practice of carrying out professional research projects and research education at higher arts institutions and, second, between the more conceptual-philosophical discourse on artistic research methodology and the rather practical and concrete literature on carrying out research for students and teachers.[30] The project’s aim is to devise a flexible approach to be used in the practice of designing research as well as within peer feedback, supervision and teaching contexts, including a conceptual-philosophical grounding and contextualisation. I do not propose either a totalitarian notion of research design or a strict method, but offer, instead, a number of categories, perspectives or lenses through which researchers, teachers and students can think about methodology.

The need and demand for a model for designing research projects and for a different kind of methodology for research in and through the arts has arisen directly from the practice of doing research, both individually and in groups, as well as within the education and supervision of master and (final year) bachelor students’ research projects. The common observation of these many and varying projects is that, in terms of research design, many often apply the tactic of seeing ‘how things go’ in a rather ad-hoc manner. The underlying hypothesis of this postdoctoral research is that the quality of research processes, outcomes and impact can be increased considerably through a more thorough yet flexible approach to research design. And this is not necessarily due to a ‘better’ design (whatever this might mean), but due to making the thought process more explicit, which is stimulated through the deliberate use of a number of perspectives, lenses or categories, as will be explored below.

Points of departure

There are three important points of departure for the proposed approach towards methodology. At the outset is what Henk Borgdorff (2017) calls ‘methodological pluralism’. He observes that, besides the fact that artistic research takes place in and through practice, “artists ’make use of a wide variety of research methods and techniques whose provenance lies in social science, humanities or technological research. […] [T]hese methods and techniques may include ethnographic research […], survey research, interview techniques or other social science-approaches, as well as historical, hermeneutic or culture-critical modes of investigation” (Borgdorff 2017, 7). This state of affairs was also reflected in the diverse work presented at CARPA6, 2019; I was not able to identify a single project that was based on only one methodological perspective.

A second point of departure is the consequent rejection of hierarchy of methods or kinds of knowledge (textual/conceptual, tacit, how-to knowledge, etc.). There is no method that is by definition more relevant or more useful than another and not one that by definition has to be included in a research methodology. My proposition is to contextualise and position the research based on a radical look at the research subject, area and context itself as well as the questions that the research generates rather than simply aligning the research within existing methodological traditions, such as quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods research. Specifically in education, in my experience the latter considerably limits the imagination regarding what and how to inquire, as students are often relatively keen to hold onto traditional methodologies, no matter how limited, while not actually engaging in the – admittedly more complex, difficult and hard-to-predict – real and open process of investigation within their area of fascination, questions for which they do not have (or might not be able to determine within the limited timeframe of their research) an answer.

As the third point of departure, I regard the research design, or the process of designing research, as a creative process (which continues during the process of carrying out the research) rather than merely an exact strategy designed to answer a question or set of questions. As obvious as this might sound, most research proposals or grant applications are still more likely to exclude this creative process from the research design rather than incorporating it as an integral part.

These three points of departure lead to a research design approach that houses a paradox and tries to accomplish two seemingly opposing aims: to provide some strictness, precision and clarity (especially for students) while at the same time remaining flexible enough to accommodate unforeseen events, processes and insights (which, in my experience, always happen and should happen). In other words, a successful methodology for research in the arts needs a flexible model with the logic of a network, to create a thorough methodological design, while providing space for flexibility and emergence (more about this later).

On the use of a model

Formal models, specifically graphical ones, usually tend to bring a number of attributes with them, such as the tendency to clarify and/or simplify more complex contexts or connections as well as blend out important aspects of their complexity. The Common Ground model of the postdoc is designed to function differently: not as a simplification of complex relationships, but rather as a framework to be used, to be filled with content, to facilitate connections that have yet to be made. In the conversation following my presentation at CARPA6, I used the metaphor of ‘good software’: good software’s functionality and use should take just a few minutes to explain to all users, while at the same time its application should provide sufficient depth, flexibility and customisation to accommodate a huge variety of users, from amateur to seasoned professional. This kind of software is built as a flexible framework that allows the user to implement it in the way she needs, including the flexibility to change her way of using it when more experienced.[31] But the software itself is not directive, not forcing the user to use it in just one particular way. In the following sections of this text I will outline the various steps taken in developing this model. Following an introduction to the overall structure of the model, its various layers will be described in more detail.

Towards research design

The model of research design I propose consists of five layers: Preparation, Collection, Structure, Time and Emergence. Preparation includes the points of departure, various underlying or root conditions, aims and research questions. Collection means, quite literally, a collection of research methods: different activities, non-hierarchical in principle and based solely on the research subject and questions as framed in the preparation. Structure leads towards a certain ordering of the collection into what I call a ‘flow of data’: how information runs through a research process, which methods are carried out in which order and the different kinds of structure that the data can have, such as single threaded, parallel or feedback loops. The layer of time goes further than scheduling and planning and is instead motivated by content as well as the notion of spending time with something, how much time we want/are ready to give. Emergence, in short, provides an opening for the unexpected, to what ‘comes up’ during the research process; this layer is arguably the most complex one and at the same time the most difficult (if not impossible) to actually design.

Collection

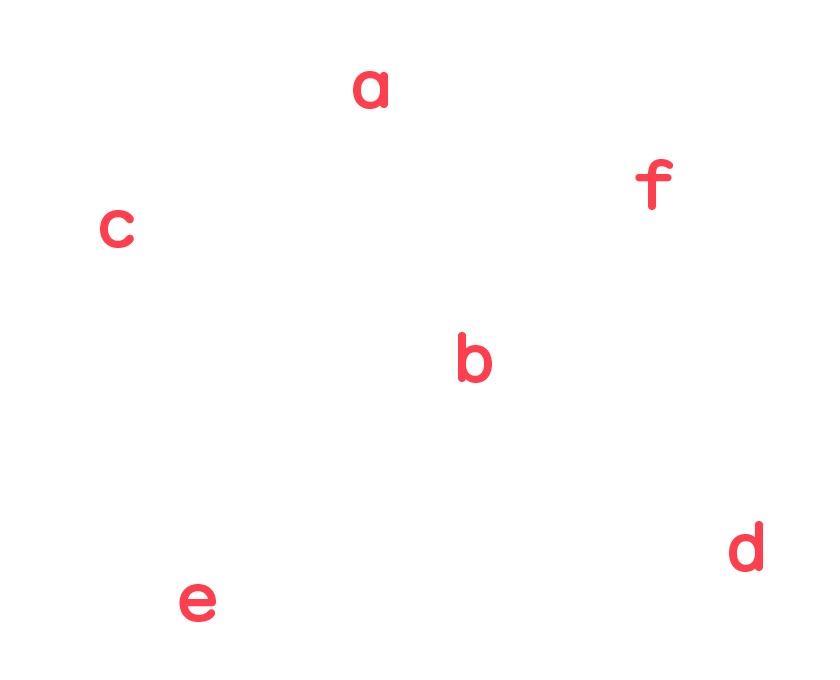

Representing it graphically, a collection of methods, in which each method is represented by a small letter, might look like this:

I will elaborate on the understanding of ‘method’ later, but it is essential to conceptualise each method not as an abstract or strictly defined part of what is traditionally called ‘data-collection’ but as an activity, something that is literally done, most often by the artist researcher, but also possibly by others.

Two aspects are essential in this initial collection: first, the close relation between each method to the research subject, area and its question(s) needs to be clear and articulated for both for the researcher herself as well as the outsider. Why is a particular method part of this collection and what might be its value and potential in the process of inquiry? Second, the collection in my model is seen as non-hierarchical and, consequently, in essence non-dependent on traditional research paradigms. Literature research, for example, is by no means more important – by definition – than a conversation with peers, an observation of a rehearsal, mapping activities or artistic experiments.

It is a conscious choice to present this as a straightforward collection, without immediately thinking about the relations between the different items and methods. Even if the various methods should be articulated and argued for, the nature of such a collection – or, actually, the activity of collecting – has certainly included aspects of brainstorming; things can be grouped and looked at, perhaps in the form of Post-it Notes or other means, to come to new ideas. Thus, the act of collecting itself can certainly be thought of as a creative and diversifying activity.

Structure

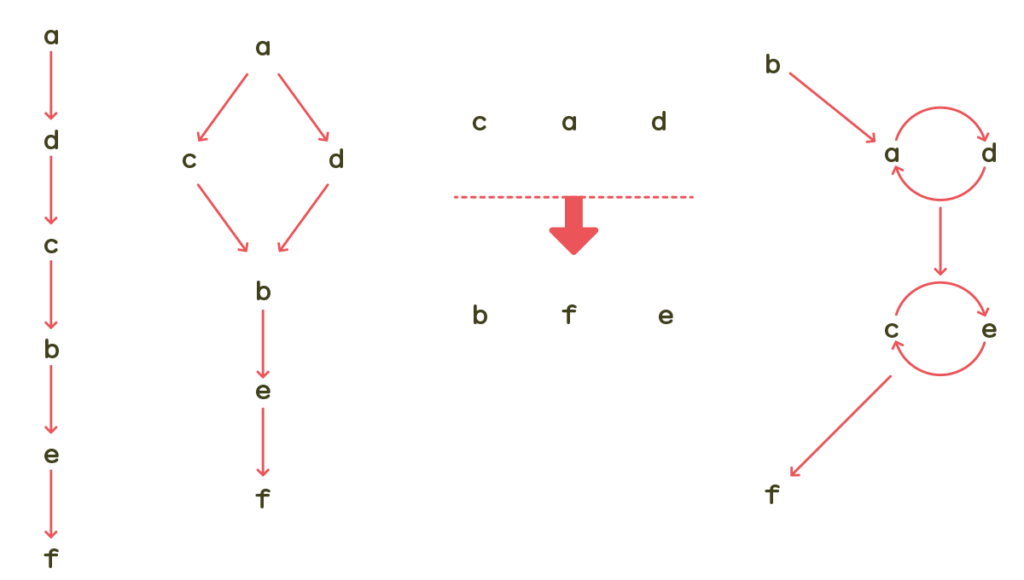

This layer aims to process the collected methods into what I call a ‘flow of data’. What comes first, an artistic experiment in the public space or interviews with artists who also work in such a context? Which steps come (which methods need to be carried out) before or after other steps? Do the various activities flow consecutively, one after the other? Are there any parallel strands, two parallel methods, that both need to have taken place before the next step, which synthesises both? Are there any feedback loops involved?

This type of visual representation of a research trajectory, diagram-like, is meant as an invitation to not only think about the research design but to also work with it by means of brainstorming or sketching or quick prototyping. In my experience, such visual representations work particularly well with students who are less experienced in research design, as they provide direct access to, and a certain transparency in regard to, often complex and longer processes. Such diagrams can provide a more immediate entrance towards research design, particularly through the modes of sketching or quick prototyping, than text alone can offer (see Gates 2018).

Time

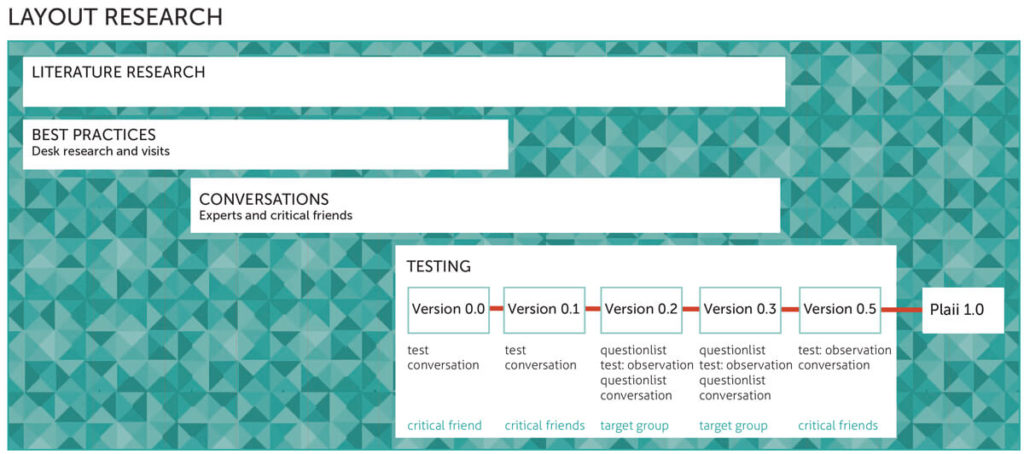

Time in research processes is often represented by a certain kind of diagram (see image 3) that typically deals with time planning, scheduling – a timeline. Such a timeline can provide insight into how the different phases and activities relate to each other in terms of time: the temporal layout of a research project’s structure.

But much more importantly, as mentioned earlier, I aim to denote something else: This layer is about spending time with something, or someone, about how much time we want to give to an activity, how much time we want or need to spend with a person or a group of persons in a particular space or surrounding. This perspective is closely related to the discourse around the notion of ‘slowness’. Philosopher Paul Cilliers notes the importance of delay and iteration – “against the alignment of speed” – and its accompanying notions, such as “efficiency, success, quality and importance” (Cilliers 2006, 2). As writer Wendy Parkins adds, the actual issue is probably not actually about fast versus slow but, rather, about ‘care’ as a central value in what she calls an ‘ethics of time’.[32]

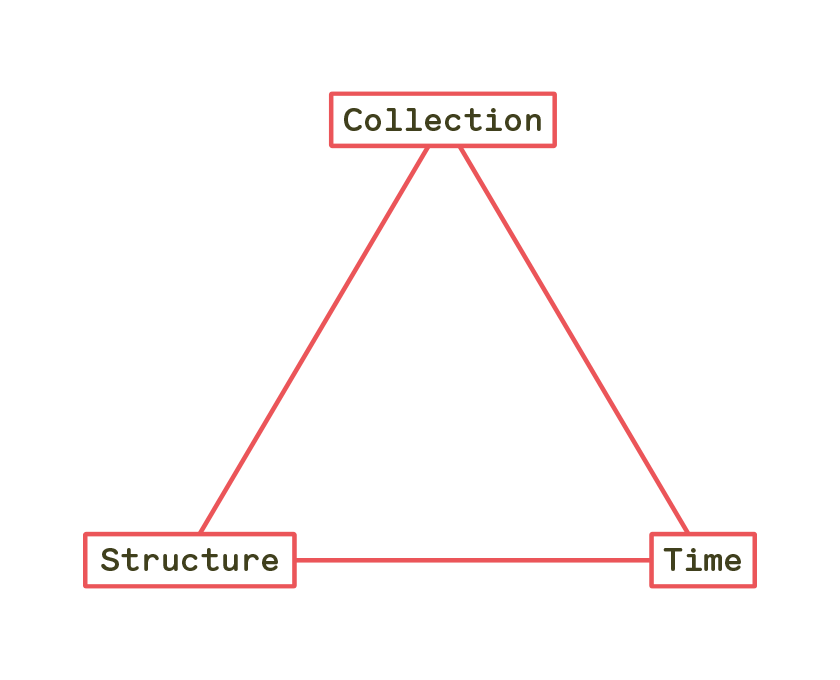

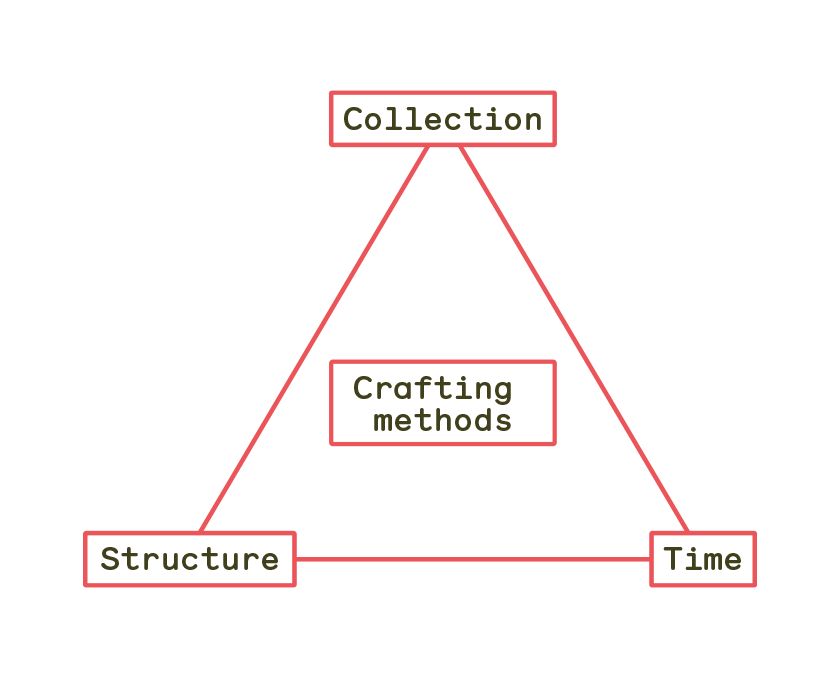

The first version of the model

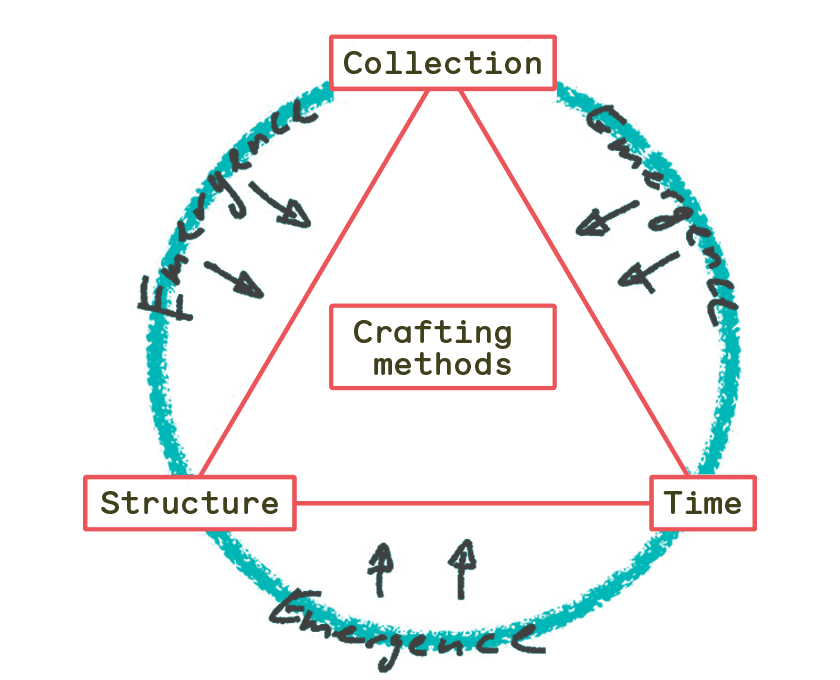

When we look at preparation as a layer that happens in advance – ‘setting the stage’, so to speak – and leave the layer of emergence aside for just a moment, three core elements remain: collection, structure and time (see image 4). It is important not to think of these elements as hierarchical or as three consecutive steps, even if the succession collection, structure, time might seem obvious (we cannot structure what we haven’t collected yet, after all, can we?), but rather as three points of a flexible network that can constantly shift in continual relation to each other. The point I make is derived from experience and practice: By structuring or giving time to elements in a collection – the methods that are envisioned to be used in a research project – the collection itself might change; the process works in an iterative fashion.

It is important to keep in mind that this visualisation is meant to denote a triangle-shaped network, with flexible and fluid connections, rather than the conventional hierarchical pyramid. Philosopher Henk Oosterling has repeatedly argued against notions of triadic structures in (the understanding of) societal structures and connections – such as ‘top-down’ or ‘bottom-up’ – and in favour of replacing them with the concept of networks.[33]

The next logical question, then, is: What is actually collected, structured and given time to? The model suggests compiling a collection of methods, but how does one deal with the very idea of methods itself? What are methods, actually? These questions have led to a concept that I have termed ‘Crafting Methods’, which I place in the centre of the design model:

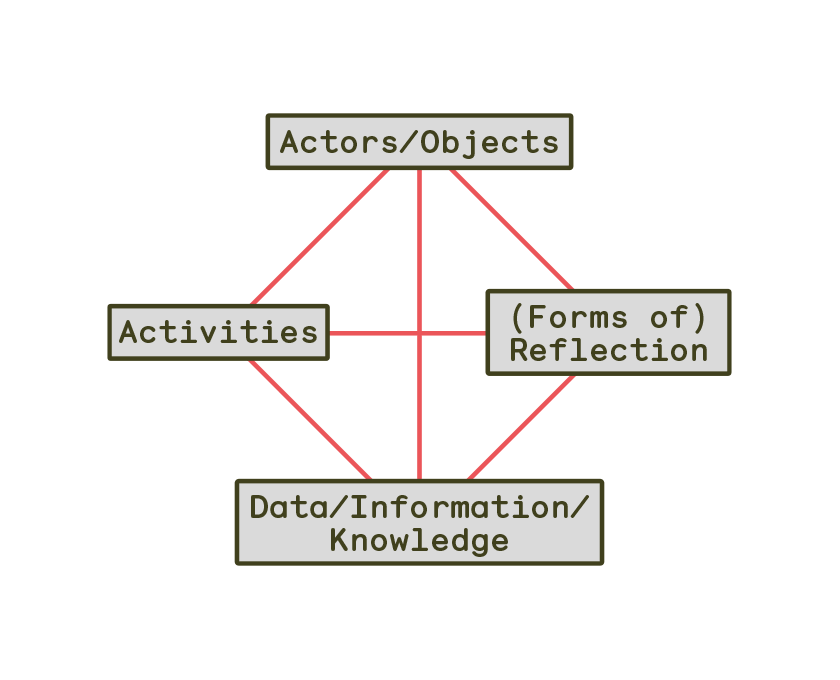

Crafting methods

Inspired by Erin Manning’s ‘Against Method’ (2015), the initial impetus for the concept of Crafting Methods is resistance: against ‘method’ as something shaped by tradition and predefined in terms of procedure, participants/actors and outcomes and for ‘method’ as something devised ‘from scratch’, from the very experience and reality of playing and making (after Manning 2015), radically oriented toward research subject and question(s).[34] The concept of Crafting Methods contains four elements (see image 6 below): actors/objects, activities, (forms of) reflection, and data/information/knowledge. All four, again, are connected within a fluid and flexible network.[35]

In the present version of the model, the naming of the first element refers to two frames of reference: ‘Actors’ recalls Bruno Latour and Actor Network Theory, and ‘objects’ draws on Graham Harman’s work and object-oriented ontology. As indicated by many others, in artistic research the practitioner/artist is often the central entity. However, actors/objects actually designates all acting human and non-human entities of a method, which might naturally include the (artist-) researcher, but obviously many more entities as well.[36] The determining question is: Who or what is involved, in which way, and assuming what kind of role or function?[37]

Activities are devised from a practical and performative approach, in the sense of ‘what is to be done’: What is the researcher (or any kind of objects) going to do, how does she/it engage? Obviously the elements of the concepts are entirely interwoven and share considerable overlap. An activity needs a human or non-human object to carry it out. Reflection can take place in many different forms: individual, collective, through conversation, writing, drawing, sketching, walking, meditating, and so on. This element might also be deliberately designed rather than just taken for granted in form and function.[38] The somewhat clumsy element data, information, knowledge aims to indicate the outcome or ‘output’ of a method: What is learned, and what progresses (possibly as input) to the next method? What do we want to learn or get out of a certain activity? Finally, these thoughts result in a first suggestion as to how to reframe what a method is or might be: A flexible network of actors/objects, activities, (forms of) reflection and information/data/knowledge.

Back to emergence

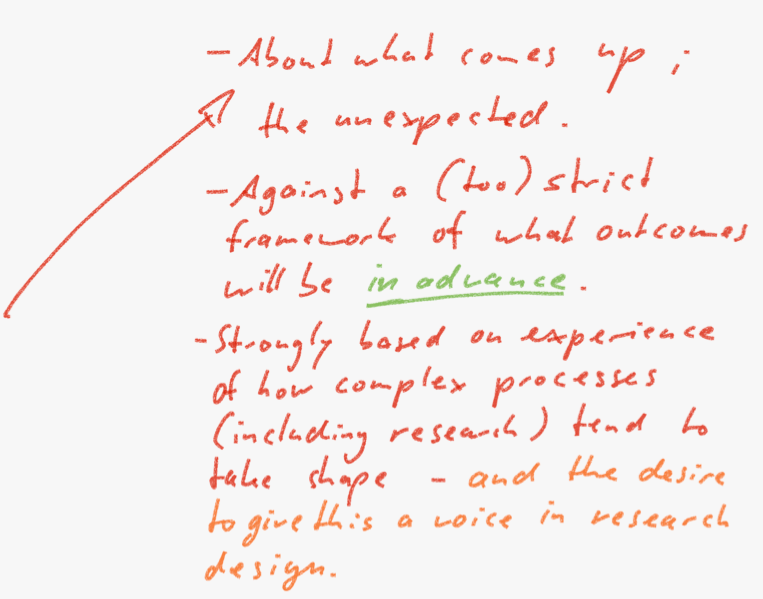

At the outset of the post-doctoral research, I was immediately aware that emergence should play some kind of role in what I wanted to address. My initial notes concerning emergence, made when the first thoughts arose:

These ideas about emergence are based on actual experience: I have never witnessed a research project that has not generated inspiring yet entirely unexpected outcomes, just as is seen in artistic creation processes. That emergence occurs, or that unexpected outcomes and processes play a role during a research project is not a new insight. Annette Arlander referred to this as the ‘sidetrack’ in research projects, during the post-presentation conversation at CARPA6: “How can you still sort of do what you promise to do [in a research or grant proposal] while not abandoning the sidetrack?” Arlander’s comment already suggests that this ‘sidetrack’ is not part of the original research design, and her comment makes a crucial point regarding the process of doing (artistic) research – or any research – for that matter. However, in most subsidy applications or research proposals this either plays no role or hardly any at all. Such texts aim to make the narrative as precise as possible, attempting to define what the outcomes are or will be, while at the same time the authors know that the outcomes can hardly be defined in such a precise manner. This situation is the origin of my desire to give emergence a voice in the process of designing research: “as a description for the way creative ideas, images, and insights can arise unexpectedly and radically distinct from whatever inputs that may have served as a groundwork for the created product”(Goldstein 2005, 4). But how can one actually give voice to something which is yet unknown?

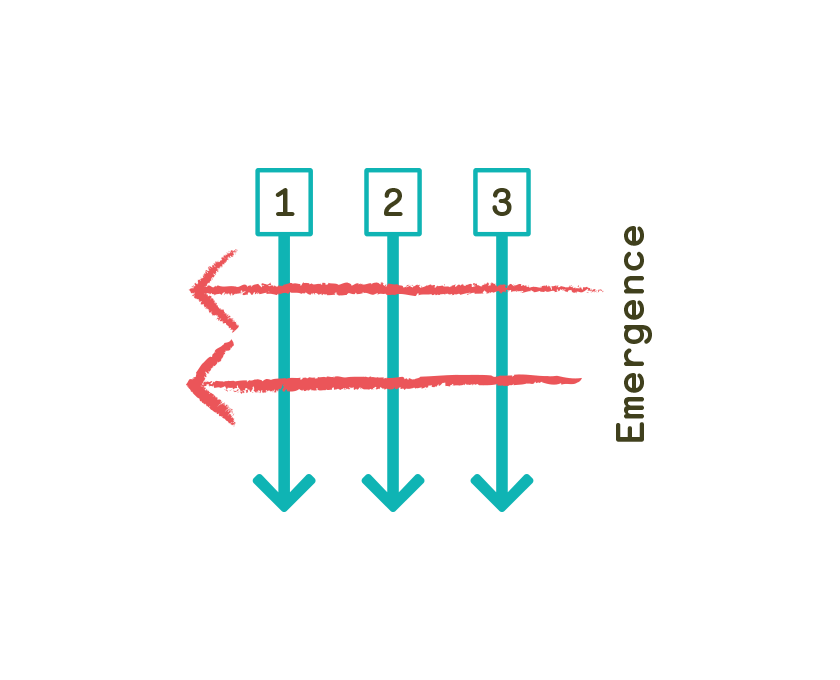

In Emergence, Stephen Johnson describes a wide variety of phenomena and contexts in which emergence occurs, as varied as slime mould, ant colonies, the human brain and software. He describes emergence as a form of higher-level knowledge and behaviour, emerging from low-level interaction in complex systems, based on “swarm logic, with no central office in command” (Johnson 2001, 233). Its central elements are “tools of feedback, neighbour interaction, and pattern recognition” (ibid.). This resonates with Peter Cariani (2008), who remarks that “[t]he full gamut of emergence encompasses new forms, new material structures, new organisations, new functions, new perspectives, and new aspects of being”(Cariani 2008, 2). This includes new techniques or even paradigms – which is in line with Johnson’s writing – as a paradigm is usually of a higher order than techniques or separate functions. Yet, and this is crucial for my argument here, Johnson reminds his readers that “it is both the promise and the peril of swarm logic that the higher-level behaviour is almost impossible to predict in advance. You never really know what lies on the other end of a phase transition until you press play and find out” (Johnson 2001, 233).

Considering the implications of including emergence in research design, in essence this means to give up some amount of control. Due to the nature of emergence as a higher-level order or higher-level intelligence we don’t have so much control about it, and only limited capacity to truly understand. This situation leaves us with the option to simply follow, pay attention to, or be faithful to the emergence. The choice is either to follow it or eliminate and ignore it – which most artistic researchers do not do. Additionally, another important characteristic of emergence is that emergence does not simply happen on its own; it is not something that just comes up unexpectedly in each and every situation or context; rather, it needs a complex system – a network of local interactions – in order to occur. Research projects and their various activities and forms of data are able to provide such complex networks. Seen in this way, emergence can also be understood as a powerful counterforce to the more solid layers in a research project.

Furthermore, this theoretical stance can provide a critical perspective on the difference between emergence within research and things that ‘just happen’ rather randomly or arise from more ad hoc types of decisions. Emergence in research design needs a strong and solid (yet flexible) design in order to occur, as otherwise there is no network of low-level interactions from which emergence can occur. Only then can it act, sometimes as a kind of counterforce to that which is already designed. There is a thin line between making use of emergence and just jumping ad hoc from one issue to whatever comes up next. Yet, I do not want to imply that working ad hoc is negative in itself. I have worked in a number of research projects that, when examined in hindsight, clearly operated according to this approach and still arrived at wonderful results and insights. That being said, I do think that outcomes and impact can be significantly improved through the act of paying attention and achieving a certain productive tension between planned and designed elements and emerging aspects.

To return to the design model, the crucial question is how to provide emergence with a place in all this. I have opted to situate it around the triangle and through its nodes, acknowledging that emergence can exert an influence on all elements, but we never know in advance on which ones.

Final thoughts

The design model and the research project of which it is part are still in the middle of their development. While the general structure and the core ideas of the model are already in place, in the future I will need to elaborate further on the essential tension between careful design, on the one hand, and space for emergence to ‘do its work’, on the other – to control and to let go. The two elements of the approach that are still in a premature stage and most in need of further elaboration are the re-framing of method and the ‘work’ of emergence. Related to this is the essential question of ‘what to do’ with emergence, actually. Is it simply about acknowledging emergence, welcoming it and providing space and time for it – ‘managing emergence’, as Haseman and Mafe (Haseman and Mafe 2010) suggest?

As for the possible applications of this model for research design, I see various possibilities. As I mentioned earlier, this model is certainly not meant as some kind of unifying ‘how-to’ method. It is offered as an approach to support the process of designing research (thus for the researcher), providing a number of perspectives, or lenses, through which a researcher or supervisor can think about a research design, helping to make the more implicit components of research more explicit. Concurrently, the model can also support self- or peer-feedback or the evaluation of a finished or in-progress research design, once again through providing categories, perspectives or lenses that can make any seemingly self-evident parts of the research more explicit and thus available for feedback. As a third application, the model can work as a framework for the supervision of student research projects. As inherently a tool rather than a method, in all situations and applications the model itself disappears after being used, thus making way for what it is devised for – a convincing methodology that is well-designed and leaves sufficient space for that which emerges.

Notes

30 In general I identify two categories of literature on research methodology, which are directed toward different target groups. On the one hand is largely conceptual and philosophical literature, targeting professional artistic researchers or doctoral students – very interesting and inspiring, but not often ‘practical’ in the sense that (bachelor or master) students or beginning researchers can actually apply its concepts when designing their research projects. On the other hand is very concrete, mostly practice-oriented literature written in an overtly how-to fashion, directed primarily towards students and teachers/supervisors. This literature addresses questions such as what kinds of methods one could use, how one conducts interviews or performs observations, etc., certainly applicable, but at the same time lacking a certain layer of depth. Both kinds of literature have their advantages and disadvantages, but the problem that I am addressing here is that these two types of literature barely connect; although both are designed to address the same area of expertise, they do not overlap and actually seem to exclude each other. My model seeks to connect these different spheres of literature.

31 In my case, the notetaking software Evernote is such an example, or the writing software Scrivener, or the music composition and performance software Ableton Live.

32 This notion is critical in the case of students, who are always working according to a strict timeline, with a maximum of two years in the case of a master’s, which is quite short when seeking to carry out a full research project. But the idea of spending time might also be understood as an intervention: an invitation, or provocation, to think in terms of achieving the greatest depth, or reflection, how to re-read, re-iterate, and so on, and not just work toward a deadline.

33 See, for example, his 2013 lecture (in Dutch) at the symposium Cultuur in Beeld. De kracht van cultuur (Culture in the spotlight. The power of culture): www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsTSasp8noE, last accessed on 21.10.2019.

34 Underlying this is the basic issue – ‘why use methods at all?’ – which was essentially Erin Manning’s initial thought, as she ‘was horrified that students were asking for methods’ (Manning, 2019, during audience conversation after my lecture at CARPA6 in Helsinki).

35 At the time of writing, these terms are still being developed and quite open for further elaboration and discussion. See hubnerfalk.com/commonground for regularly updated information on the project and its terminology.

36 Such as musical instruments, spaces for rehearsal or performance, lighting or a VR installation, just to name a few possibilities.

37 During the conference we have seen many different examples of this, such as the Juniper tree as not only an addressee of Annette Arlander’s text but also a crucial object in her research; 750+ participants-as-researchers – including children, parents and animals – in Sybille Peters’ community art research projects; computers and code in Hanna Järvinen’s work. All these different actors/objects can play a role in designing and carrying out a method.

38 See, for example, the work of the HKU professorshipArt and Professionalisation, where work forms, based methodologically on action research, were initially developed to provoke change in a wide variety of professional settings, to later become reframed as research methods. In particular, the form of (often collective) reflection is an essential part of this work. Another example is the reflection element of a workshop at the Symbiont conference on 16.11.2018 at Calgary University, where our group of participants (Claire French, Gretchen Schiller, Fredyl Hernandez, Maria Angelica Viceral and myself) carried out a workshop and chose to reflect with the entire group through writing and drawing with chalk on a board, entirely without talking, as a kind of meditative ending of an intense practice session.

References

Borgdorff, Henk. 2017. ‘Reasoning through Art’. Accessed 6 October 2019. www.universiteitleiden.nl/binaries/content/assets/geesteswetenschappen/acpa/inaugural-lecture-henk-borgdorff.pdf

Cariani, Peter. 2008. ‘Emergence and Creativity’. Accessed 5 October 2019. pdfs.semanticscholar.org/76b3/3ab7d44bd34b7c213997d953ed8feec38a8c.pdf?_ga=2.46681639.1089917717.1570250198-454848092.1570250198.

Cilliers, Paul. 2006. ‘On the importance of a certain slowness.’ In Emergence: Complexity and Organization, 8.3. Accessed 1 November 2019. journal.emergentpublications.com/article/on-the-importance-of-a-certain-slowness/.

Geerling, Annemarie. 2015. Let’s plaii. Een ontwerponderzoek naar interdisciplinair improviseren met kunststudenten [master thesis]. Utrecht: HKU.

Gates, Peter. 2018. ‘The Importance of Diagrams, Graphics and other Visual Representations in STEM Teaching.’ Accessed 17 October 2019. www.researchgate.net/publication/319086868_The_Importance_of_Diagrams_Graphics_and_Other_Visual_Representations_in_STEM_Teaching.

Harman, Graham. 2016. Immaterialism.Objects and Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Haseman, Brad & Mafe, Daniel. 2010. ‘Acquiring Know-How: Research Training for Practice-led Researchers.’ In Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts, eds. Hazel Smith & Roger T. Dean, 211–228. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Johnson, Steven. 2001. Emergence. The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities and Software. London: Penguin.

Latour, Bruno. 2005. Reassembling the Social. An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Manning, Erin. 2015. ‘Against Method.’ In Non-Representational Methodologies, ed. Phillip Vannini, 52–71. New York: Routledge.

Oosterling, Henk. 2013. Presentation at the at the symposium Cultuur in Beeld. De kracht van cultuur (Culture in the spotlight. The power of culture). Accessed 21 October 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vsTSasp8noE.

Parkins, Wendy. 2004. ‘Out of Time. Fast subjects and slow living.’ Time & Society 13 (2/3): 363–382.

Falk Hübner

Falk Hübner is a composer, researcher and educator. Currently he is working on a postdoctoral research on artistic research methodology at the HKU University of the Arts Utrecht, next to being core teacher for research at HKU Conservatoire. Next to his work at HKU he works as research supervisor for the ArtEZ Master in Music Theatre, and as director for research and writing at ArtEZ International Master Artist Educator, a master programme with a radical vision on art as conflict transformation.