Treats the uses of rhythm, focus on action, emotion, and transformations (spatial, temporal, energetic variations of action and movements) as well as transfers (to put a specific action or movement into another context) and the dramatic uses of stage space.

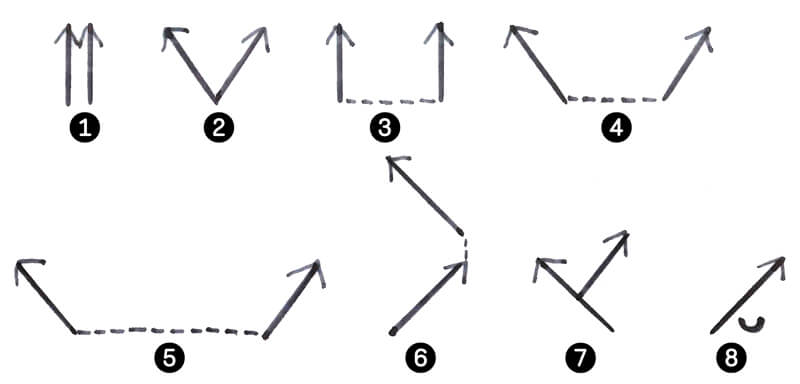

The eight basic positions of the feet (see sketch): Without perfect posing of the feet into position after a movement, there is no physical art. The positions should be repeated in each session, maybe even as a drill. If the feet are turned out, they should be at an angle of about 45 degrees. The real professional always sets his feet in the correct manner, and he is always seen landing in the correct position, not at random!

Position exercises 2.107–2.111

Exercise 2.107:

- The basic position (or samam): feet parallel together is the position of ‘collection’ and concentration.

- The tree position (the modified first position of classical ballet), with feet at an angle of 90 degrees, heels together, is a ‘cultured’ position. (The calves in a turned-out position look more aesthetic than the front side of the leg.)

- The parallel position: From the previous position, turn the toes outwards. The feet are again parallel. You now stand as large as your pelvis. This position gives good stability and is helpful for the study of movement.

- The Eiffel Tower position, from the parallel position, turn the feet out again (like a larger tree position, with a distance of one to 1.5 feet in between. When the position is done in demi-plié it is called chauk). (Eiffel Tower and chauk are the most common positions of European and Asian dances and dance theatre.)

- The large position, preferably with deep sitting (plié, heels down) with a distance of about three feet between the two turned-out legs. In plié, the position is called ‘samurai position’. (The pelvis may be tilted backward). It is the position of maximum stability, as used in martial arts.

- The open position (a modified 4th position of classical ballet), feet turned out (each at 45 degrees), heels in a vertical line, one heel in front at a distance of at least 1.5 feet (if the front leg is in plié and the back leg is outstretched and anchored behind, the lunge, also called the fencing position) (the backfoot can be fully in contact with the floor, or rest on the ball of the foot.) If the movement is done to the side, it is called a side lunge.

- The Chinese T-step. The backfoot is turned out and the other foot’s heel touches the middle of the backfoot. (The front foot is flat down or resting on the ball of the foot.) It replaces the 3rd and 5th position of classical ballet. This is a very practical position to start movement from and is endemic in Chinese opera.

- The female position[170]: (tabu). This is the second asymmetric position. Feet are turned out, each at 45 degrees. With one foot behind the other on the ball of the foot, this is a graceful position and is an easy starting position for movement.

Practise the positions, one by one, with different body positions:

Exercise 2.108: In half-plié, the heels rest on the floor

Exercise 2.109: In deep plié with lifted heels

Exercise 2.110: With relevé

Exercise 2.111: With plié and relevé

The 4 basic positions of the arms[171]:

- Preparing position: Rounded arms about 15 cm in front of the body

- 1st position: Rounded arms forward

- 2nd position: Rounded arms to the sides

- 3rd position: Arms rounded over the head

Positions of the arms exercises 2.114–2.119

Exercise 2.112: Practise the four basic arm positions as described above.

Exercise 2.113: With one arm position in between: Right arm in 1st position, left arm in preparing position, right arm in 2nd position, left arm in 1st position, etc. Connect the arm movements in flow.

Touching the floor – different steps to practise

- Touch the floor with the pointe (top of the toes)

- Touch the floor with the ball of the foot (heel lifted)

- Start as no. 2, lower the heel with a sound

- Touch the floor with the heel, the wrist is flexed

- As no. 4, put the sole of the foot down

- Flat step

- Slap (to side, on the outer border of the foot)

- Rubbing, gliding step to the side

Note! Basic positions and steps must absolutely be automatised!

Exercises 2.114–2.119

Exercise 2.114: Half plié, full plié and demi-pointe. First position, with feet together, demi-plié (the heels do not leave the floor!), raise the heels, relevé on demi-pointe, back to starting position, bend into a deep plié (the heels lift off the floor!) raise, and relevé on demi-pointe, back to plié and to the starting position, change to tree position (also here one demi-plié, one full plié) to parallel legs (same movements), open to parallel position (same movements), open to Eiffel Tower position, (same movements), to large position (same movement) to T-step position, modified 5th position and female position, all with the same movements.

Exercise 2.115: Ta-ki-ta. (Flat right, r ball, r down). Tree position, demi-plié: lift and lower the sole of the right foot again with an accent (ta), lift the left foot, put it with an accent on the ball of the foot (ki), lower the left heel with accent (ta). Practise eight times to the right and eight times to the left.

Exercise 2.116: Ta-ka-ti-mi: From the tree position, demi-plié: ta= right foot flat step, ka= repeat, ti= put left ball of the foot behind the right foot, mi= lower the left heel. (Same to the left). Practise eight times to the right and eight times to the left.

Exercise 2.117: tei-ya-tei: From a parallel position, tei= right flat step forward, on ya= lift the left heel, and put it beside the right leg, tei= lower the left heel.

Exercise 2.118: Learn a couple other foot works and steps, such as from Flamenco, tap dancing, Irish, Hungarian or Indian dance, or invent steps and step combinations in various rhythms.

The bhaṅgis. Artistic poses have their mathematical laws, such as the ‘Golden Ratio’, in European art, or the aesthetic laws written down in the Indian Silpasastra (the science of creative arts as painting, architecture and sculpture).

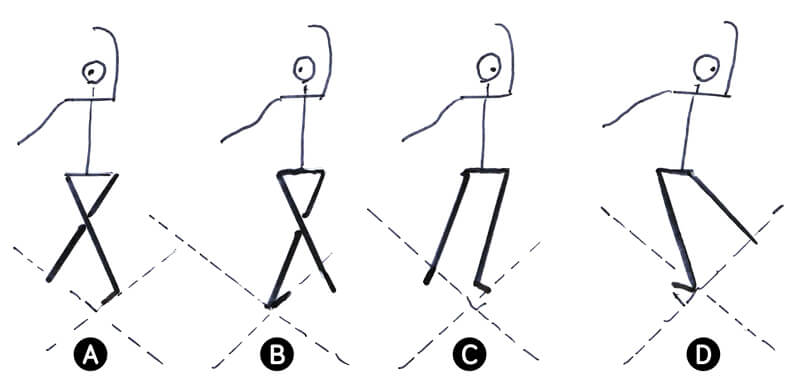

Exercise 2.119: Tri-bhaṅgi, 3-bends (see sketch). Stand in the tree position, demi-plié. Lift the right heel, push the left hip out and up, bend the torso parallel to the right, bend head and neck to the left.

In Indian dance – as in Odissi style in the sketch above, the focus lays on the frontal translations of three body parts (head and neck, bust and hips) in two dimensions. In classical ballet (see sketch) howsoever, the focus is spatial and diagonal.

About the centre of energy, the centre of movement

The energy centre of the body, considered to be about 2–3 cm below the navel, is called hara, the point from where one attracts things and the point from which one pushes things. There lies the balance centre of the body: the pelvis and its two opposite muscular forces – the abdominals and the buttock muscles, (studied in body education level I!) – are responsible for standing and moving functionally. These counterforces keep the pelvis in place and are the basis of balance. In Grotowski’s training, the impulse centre was considered to be in the lower back.

The Chinese speak of the yao, as energy centre, encircling the body between the bottom of the rib cage and the top of the pelvis[172] around the waist, but it does not include the lower back. The handstand is one of the first and most important exercises for the yao, along with the back bend.

For mime, the centre of impulse is enormously important. Polish mimers such as Tomasevsky considered the lower back as the fulcrum of movement, and so did Grotowski. For Czech mime – such as Fialka and Sladek – the movement and impulse centre was the chest, the emotion centre. Also, Meyerhold considered the solar plexus as the centre of movement. For the mime of Marcel Marceau, trained by Decroux, as well as for Lecoq, movement impulses started in the knees.

My Balinese mask-dance teacher, I Deva Sayang, taught me two centres of movement: one in the middle under the shoulder blades and the other in the lower back. From here the body moves. The actor is himself the manipulator of a marionette, his body!

The posture, position or pose[173] is an immobile body position. The body stands still, but the mind is mobile! To stand immobile in ‘hao’, in a ‘perfect’ pose, is a classical Chinese exercise.

Centre exercises 2.120–2.126

Exercise 2.120: Stand immobile in a ‘correct pose’ for 5–20 minutes and become aware of the tensions and relaxation in the body, and the direction of the limbs, head and eyes. This is a feature from the Chinese opera classroom.

I add here some pre-exercises from kalaripayattu[174]. It is said they have health effects like yoga asanas. They are starting positions for swift attack and defence.

Exercise 2.121: Sitting leg (iruthi kaal): Squat or sit on the floor, with one leg bent and the other leg extended, in line with the hips. The body in the same direction as the stretched leg, straight, the hands on the sides of the thigh of the extended leg.

Exercise 2.122: The elephant (gaja) as studied in level I exercise 1.167.

Exercise 2.123: The lion (simha vadivu): Samurai position, left leg slightly forward, heels in line, upper body in the direction of the left leg, and straight, arms at angles of 90 degrees at most, left arm with palm forward over the head, right arm with palm down held at the side, head and neck straight.

Exercise 2.124: The horse as studied in level I exercise 1.168.

Exercise 2.125: The cat (maarjaara vadivu). Sit with turned-out hips on the right knee, the left heel placed close to its toes. The right hand lies on the right knee, left arm extended over the left knee. Lie prone, the left leg with bent knee, hands under the chest, rounded as claws, head lifted.

Exercise 2.126: The fish (matsya vadivu) Stand firmly on the left leg, bending the right leg upwards behind and stretch the left hand forwards showing the open palm, bending the right hand behind, the elbow pointed backwards[175].

Action analysis exercises 2.127–2.128

Exercise 2.127: Study ‘the picking the apple-exercise’ (level I, exercise 1.304) with a metronome, stylised and as a drill.

Exercise 2.128: Variations of size of movement (smaller, bigger, with upbeat (otkas, and with ending accent)).

The uses of space exercises 2.129–2.130

Exercise 2.129: A group of 3–7 people moves in different ways through the space.

The placing of the individual person on stage[176]: 1:1/ or: 1:1:1:1…

Exercise 2.130: One person walks on stage, then the second person enters. Both walk on stage and finally A stops at a place, and B searches for the spot where both have (spatially seen) the same value, the same ‘weight’. The third person enters, the first person starts to walk again, and all three finally find positions of equal weight. The fourth person enters, same procedure, a fifth, a sixth and a seventh, creating balance on the stage. All seven must be considered as individuals with the same value.

If the individuals gather, they become a group, a chorus (X).

Protagonist and antagonist, their choruses and reactions: exercises 2.131–2.133

The birth of the hero from the chorus. 1:X

Exercise 2.131: 8, 12 or 16 people walk freely on stage, and engage in short interactions. On a given sign, they freeze. The best placed person in the space will be the leader (protagonist, hero). The others gather behind him.

The second best-placed person is the antagonist, the opponent. People standing close gather. The two heroes with their groups stand opposite each other.

Exercise 2.132: If hero A moves forward, his group also moves forward or spreads out. If he retires, the chorus retires or stands closer together.

Exercise 2.133: Let protagonist and antagonist have a physical dialogue, only through the chorus reactions: First A reacts, second his chorus, third B reacts, fourth B’s chorus.

The uses of space of the character entry, placing and exit

Entry, standing spot and exit of a character already provide information about the character. The placing of the character on stage is an ancient art and has been very important in baroque theatre. The character reveals himself and his status by his first placing on the stage (confidently in the middle, turns his back, in profile, etc.)

The characters of Asian classical theatre have their own specific stage entries. The actor of Chinese opera enters the stage from the left (as seen from the auditorium)[177], and delivers there his self-presentation, (ziabao jiamen)[178]. He tells or sings his name, where he comes from, where he is on the way to, what is his intention, his emotions, etc. He gives all the necessary information about himself to the audience. There are beautiful set choreographies for the first presentation of a character (male and female warriors).

The important Kabuki characters enter by the hanamichi, a wooden bridge through the auditorium. There, he can be watched properly and close by. He will not directly pass, but will ‘dance’, speak, turn and act and present himself to the public.

In Kerala, curtain looks are used as the dramatic presentation[179] of a character. The main kathakaḷi character enters by a curtain look. He will appear from behind a hand curtain (tiraśśīlā), held by two stagehands, and step by step, through movement, and lowering the curtain, he will reveal himself. The way a character enters the stage is crucial!

If his entry is very short and direct, as often happens in contemporary theatre, there is no time to present the character before he is entangled with dramatic problems and partners.

The uses of space exercises 2.134–2.143

Exercise 2.134: Let a character enter: with a specific walk to traverse the stage by using space in different ways (curves, zig-zag, circles, spirals, turns, etc.) to find the first spot to stand.

Exercise 2.135: Same exercise as above, with the accompaniment of percussion.

Exercise 2.136: Use a (mask) character and compose an entry from the left to a specific spot, and a short self-presentation with movement (an action, emotion, etc.). Improvisation.

Exercise 2.137: Mark a bridge through the auditorium, use a (mask) character and let it enter by the bridgeway (with audience on both sides), with an important action, specific for the character. Improvisation.

Exercise 2.138: Use a piece of cloth, about 2.40 x 1.80 m. as a hand curtain held by two persons. Start behind the curtain and make your appearance. Improvisation.

Exercise 2.139: Use a towel covering only your face and make your entry. Improvisation

Exercise 2.140: 2–4 (mask) characters make their entry together. Improvisation.

The exit of a character from the stage[180] is important as well. Let the mask character be seen one last time in an adequate, frozen position, just before he disappears into the wings.

Exercise 2.141: Create a (mask) character exit.

Exercise 2.142: In groups of three (mask) characters together: Invent space patterns to enter, place them and exit from the stage in a cluster, row, line, broken line, etc.

Exercise 2.143: Try to define characters through their place on stage (‘The one’ standing in the corner, in full light, the one looping around, the one standing with crossed legs, open legs, etc.) and discuss the effects.

The use of rhythm or various speed and rhythm patterns

Rhythms have already been practised in level I. Now scenes are connected to rhythm.

The use of rhythm exercises 2.144–2.152

Exercise 2.144: Rap presentation. A beats a percussion rhythm, B recites, raps or sings a short text (name, address, age, intention, emotional state, etc.)

Exercise 2.145: Playing percussion rhythms. The group or an individual actor play percussion rhythms (on instruments, wooden blocks, clapping, body percussions) on units of three (valse), 4, 5, 6, 7 (used for lyrical storytelling), and 8, 9, 10 (for frightening actions, such as sharpening knives).

Exercise 2.146: Repeat walking and acting in the slow unit of 48 beats (as described in the exercises for level I).

Exercise 2.147: A practises a short scene with a mask or without. B watches it and creates an adequate rhythm unit for it and drums it. A adapts his actions to the rhythm, using heavy beats to accentuate actions.

Exercise 2.148: Same exercise as above. C underlines certain actions of A using a second percussion instrument.

Exercise 2.149: Find adequate music for A’s action. The music should underline the emotional state of the action.

Exercise 2.150: Find music (or do it by sounds) that replaces the scenography of the action (for example in the city, in the forest, on the water).

Exercise 2.151: Find music that works against the intentions of the character (for example: they want to sleep, but there is that sweet song disturbing them…)

Exercise 2.152: Find music that works ‘physically’ against the music. (The music hits, kicks… A falls over it, twists it, sucks it, cuts it, etc…)

Breathing exercises 2.153–2.158

Exercise 2.153: The picking the apple exercise. Movement by inhaling. Stand immobile and exhale. Be aware of the situation.

Exercise 2.154: Same exercise. Movement by long exhaling, stand immobile when inhaling. Be aware of the situation.

Exercise 2.155: Same exercise. Movement by holding breath for three seconds after inhalation (apnea) then move suddenly, quickly and violently. Stand immobile, exhale and inhale. Be aware of the situation.

Exercise 2.156: Same exercise. Practise with six movement forms, one by one: wavy movement, concave, convex, acceleration, deceleration and by saccades (staccato).

Exercise 2.157: Adding a long sound (consonant with vowel, such as mmmaaaaa….)

Exercise 2.158: Improvisation. You are at a party and are offered different drinks on the right and on the left. Transfer the apple exercise, seeing, taking, drinking, putting away, making choices, etc.

In mime, there are sometimes swift character shifts. The following exercise serves as preparation and develops the dynamics of movement.

Dynamic character – energy – speed – and direction changes[181]

An important and effective series of drill exercises for an agreed body and training alternation of form, direction, and rhythm.

Dynamic character exercises 2.159–2.169

Exercise 2.159: Characters. Each person composes three purely physical characters, based on alternation: A body posture, a walk, arm movements and hand positions. Maybe one position with a large stance, round back and small arm movements, a long, thin one with ample arm movements, etc. Each character has been given a very specific position for stopping movement (in the middle of a step, maybe).

The three characters are called A, B and C: The leader proposes: Character A: walk, stop: The actors freeze and wait for the next command: Character B. now! The participants, directly from the last stopping position, must move like character B without intermediary movement. The exercise goes on for quite some time, until all the three characters are well established in the body memory of the participants. If they produce the energy and focus to solve the task, switch to the next exercise.

Exercise 2.160: Stop posture. For each character three different stop postures are invented by the actors. The instructor orders the characters, the participant decides which stop to use: 1, 2 or 3. (The actors must learn characters and stops exactly).

Exercise 2.161: Tempo. Each character should move in a normal, sportive tempo, in slow motion and at speed. The instructor orders ‘stop! Slow motion. Go!’ (or quick, or medium). The participant decides spontaneously after each stop which character he wants to use next (and with one of the varying three stop-points at the end), and changes his speed immediately on go: he must move without intermediary movements.

Exercise 2.162: Directions and turning: Each character can move in four directions: (North is always in front of the nose, south towards the back, east to the right and west to the left.) Depending on whether the stopping leg is to the right or the left, the difficulty turning to a new direction is easy or more difficult! He has the following possibilities: Changing direction with a quarter-turn, a half-turn, a three-quarter-turn, or a full turn (both to the right or the left side.) From the stop posture, the participant changes direction and walks immediately with one of the two other characters, at a new speed.

Exercise 2.163: Flourish. For each character, the actor adds (before the ending posture!) a short, supplementary movement, a fancy, with a leg, a foot, the trunk, hip, arms, head, etc.

Exercise 2.164: Hand accent to end (or foot action, sometimes) from the wrist or only with the fingers. This hand accent, a mudra (hand gesture) as part of the movement into the ending position. (Each character should have his flourishes and hand accents.)

Exercise 2.165: The actors now move after having chosen their character, the stop posture, speed, direction, flourish and hand accent. The instructor orders only stop and go. Sometimes these stops are longer, sometimes shorter!

Exercise 2.166: The actors now perform the full exercise without the orders of the instructor, by themselves, without slackening energy, focus and form, constantly alternating character form, stop point, speed or direction, with or without flourishes and hand accents.

Exercise 2.167: Individual action as above. One more element is added: The actor decides how many steps the character takes: a few, many, 4–6 (the usual!).

Exercise 2.168: Two to four participants together. When one actor stops, the next immediately starts walking. Only one actor at a time moves! Now, the direction of the actor and where he stops is of importance for who is responding with the next walk. (Standing close by, a frontal stop, etc. may be reasons.) If two actors start at the same time, one must withdraw his move.

Exercise 2.169: The entire group works together. Only one person moves at a time.